Studying as an international student at a tertiary education institute can present various challenges that may lead to psychological distress. Research has indicated several factors contribute to distress among international students in Australia (Alharbi & Smith, 2018; Huang et al., 2020; Orygen, 2020; Wu et al., 2015) such as physical separation from family; difficulty in forming new friendships; cultural differences; language barriers; financial difficulties; racism, discrimination or prejudice; culture stress; and poverty. Additionally, variation exists in help-seeking behaviour, influenced by cultural differences (Lu et al., 2013). To address these issues, some studies have explored the efficacy of alternative therapies such as expressive arts therapy compared with that of traditional talk therapies (Davis, 2010; Hsieh, 2019; Watson & Barton, 2020). However, the research in this area is limited and deserves further investigation. The literature review of the current study summarises current knowledge on alternative therapeutic approaches aimed at mitigating distress among international students in Australian university settings. This mixed-methods study, using art-based autoethnography, found a reduction in distress levels and the emergence of positive themes in reflections. It concluded that reflective art-based activities may help international students manage their emotions and foster a positive mindset, and suggested future research into how colour choices in art might reflect distress levels. Regarding the term international student, this study adopted the definition by Kelo et al. (2006), namely, “a student who takes an action to undertake or study study-related activities in the country to which he/she has moved for at least a certain unit of a programme or for a certain period of time” (p. 210).

Literature Review

In January 2023, the number of international students studying in university in Australia was approximately 230,000 (Australian Government Department of Education, 2023). According to a survey conducted by Orygen (2020), 36% of international students reported that loneliness and social isolation had negatively affected their mental health while studying in Australia. Factors contributing to this included physical separation from family and difficulties in forming new friendships, particularly during the initial adjustment period (Orygen, 2020). Cultural differences were also identified as a factor that led to stress since individuals had trouble acculturating to Australian culture and society—for instance, familiarising themselves with services and finding employment (Udah & Francis, 2022).

Language proficiency emerged as another critical factor affecting international students’ adjustment to studying in Australia (Orygen, 2020), despite the students meeting minimum standards in English proficiency. For example, 21% of students revealed that language barriers prevented them from seeking help and 13% felt these barriers adversely affected their mental health (Orygen, 2020). Furthermore, low English proficiency was linked to academic challenges such as understanding course content and performance in exams (Alharbi & Smith, 2018), thereby exacerbating stress levels and affecting mental health significantly. Additional stressors contributing to distress among international students were noted as financial difficulties; experiences of racism, discrimination or prejudice; cultural adjustment stress; and economic hardship (Huang et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2015).

Existing Interventions in Australia

Given the challenges faced by international students, several existing interventions implemented in Australia aim to help them manage their distress levels. Generally, Australian universities offer counselling and psychological support services tailored for international student populations. However, research has indicated that some international students are reluctant to seek counselling, believing it may not be beneficial (Gan & Forbes-Mewett, 2019). In response to this reluctance, some institutions have introduced psychological support through online collaboration software (such as Zoom) to address cultural differences (Forbes-Mewett, 2019). Despite these adaptations, Lu et al. (2013) noted that students’ limited awareness of their psychological needs and available support services remains a barrier to seeking professional help.

Despite these barriers, the literature has reported successful intervention programs for international students. For instance, Smith and Khawaja (2014) and Elemo and Türküm (2019) found that on-campus group therapy programs based on cognitive behavioural therapy principles significantly improved participants’ psychological adaptation and coping self-efficacy. Similarly, Xie and Wong (2020) demonstrated improved mental health and overall quality of life in international students in Hong Kong following a course of individual counselling based on cognitive behavioural interventions.

Various therapy modalities have also shown benefits for international students. Qualitative studies by Watson and Barton (2020), Hsieh (2019), and Davis (2010) explored art-based therapy workshops—some incorporating mindfulness activities—conducted face-to-face or online over 3 months at Australian universities. Watson and Barton (2020) found that participants gained deeper self-understanding which improved their positivity towards studies, future prospects, and overall wellbeing. Davis (2010) observed increased personal growth and autonomy among international students, while Hsieh (2019) highlighted students’ enhanced insights into overcoming acculturative stress, for example, they reidentified their identity, reflected on obstacles and their own culture’s value, and reshaped personal narratives of success.

Purpose and Aims of the Current Study

While studies have supported the efficacy of using arts to promote wellbeing and reduce stress (Davis, 2010; Hsieh, 2019; Watson & Barton, 2020), investigations into such practices among international students remain in the early stages and are predominantly based on qualitative thematic analysis studies. To date, none have explored the lived experiences of international students using the autoethnographic method which is renowned for capturing nuanced cultural perspectives directly from participants. Therefore, this study aimed to bridge this gap by investigating the effectiveness of art-based intervention from the perspective of an international student researcher, employing an autoethnographic approach. The primary goal of this research was to explore the question “Does engaging in art-based activities and reflecting on the process reduce distress in an international higher education student studying in Australia?”

Method

Mixed Methods Research

This study used a mixed methods research (MMR) design to address the research question. MMR is a comprehensive research methodology that integrates various methods to collect, analyse, and interpret both qualitative and quantitative data systematically within a single study (Bowers et al., 2013; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). This approach enables researchers to explore research questions with both depth and breadth (Enosh et al., 2014), combining the strengths of qualitative and quantitative research while mitigating their respective weaknesses (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004).

Autoethnography

Autoethnography is a qualitative research approach in which the researcher reflects on personal experiences through narrative writing using autobiographical stories to gain a broad cultural understanding (Creswell & Poth, 2017; Ellis & Bochner, 2000). Positioned within ethnographic inquiry, autoethnography utilises the researcher’s autobiographical materials as primary data (Chang, 2008). Accordingly, the researcher assumes dual roles as both participant and observer, and both subject and researcher, thereby offering an insider’s perspective through an outsider’s lens (O’Hara, 2018).

Art-Based Autoethnography

Art-based autoethnography supports the experiential depth that emerges within the creative process to contribute data to the research. It facilitates the use of the senses in creating a process, providing a rich data source capable of describing visual, tactile, and sensorial experiences (Barbera, 2009). Given the individual and subjective nature of the art-making process, conducting qualitative art-based autoethnography is ideal for capturing emotions, reflections, and interpretations of this personalised journey. It enables self-reflection within cultural contexts, offering specific insights into the experiences of individuals with similar backgrounds.

Research Design

The primary variable of interest in this research was distress. Utilising the MMR methodology described above under the heading Mixed Methods Research, distress was measured both quantitatively (Visual Analogue Scale [VAS]; Brazier et al., 2007) and qualitatively (art; reflections on art produced) twice a week during a pre-determined intervention segment which lasted for 8 weeks from the second week of August to the end of September 2023. Data collection occurred every Tuesday and Friday at 8 p.m. in the participant researcher’s bedroom, specifically at the desk. This schedule and location were consistently maintained throughout the intervention period, and all activities were conducted alone. Following this intervention phase, the participant researcher distanced herself from the data (Ellis, 2004) by putting the project aside for a period of 2 weeks. Subsequently, the participant researcher returned to analyse the data using a paired samples t-test (IBM, 2023) and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Throughout the study, ethical considerations were strictly adhered to in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2018).

Data Collection

At each pre-determined intervention segment, the participant researcher engaged in the following procedure:

I arrive at the desk in my bedroom at 8 p.m. and meditate for 5 minutes to become present. Then, I rate my current distress levels using the VAS and I record my perceptions and experiences of that distress. Remaining present, I allow time for myself to feel what emerges and what I am inspired to draw, then I complete the task. Following the art activity, I re-rate my distress using the VAS and reflect on my experience, for example, what I noted cognitively, somatically, and behaviourally.

The reflection process on the image drawn followed McNiff’s (2004) guidelines, utilising standardised prompts. McNiff encouraged the drawer not to judge or analyse their artistic expressions, allowing the images to take on healing powers, thereby enabling reflection from a non-judgemental perspective. This approach created a space for the participant researcher to reflect on and cope with distress throughout the process. The standardised prompts for reflection, as suggested by McNiff were:

First, speak to the image as yourself, imagining that you are speaking to a person.

Look at the image carefully. Look deeply as if you are watching another person. Begin to speak by telling this “other” what you see in detail.

How does what you see make you feel?

Next, become the “image’s speaker”.

How does the image feel about being seen in that way?

What does the image need?

What does the image want me to know? (p. 85)

The participant researcher repeated this process at each session during the data collection period and stored all data in a private location.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Data

A paired samples t-test (IBM, 2023) was used to compare the means of VAS scores collected prior to engaging in the art process. The means of VAS scores were collected following engagement in the art process.

Qualitative Data

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was adopted to analyse all image reflections per data collection segment. Analysing each discrete data collection segment as a unique dataset enabled the detection of changes in themes over time, thereby capturing whether the reflections indicated changes in distress levels.

Positionality and Bracketing

Regarding my positionality as a researcher, I am a female international student from Hong Kong. I have experienced hesitation to ask for help—a concern mentioned in the literature reviewed. Growing up in a culture in which people are often discouraged from seeking help and are frequently compared with others, I internalised a fear of making mistakes and a desire to appear competent. This cultural background, combined with English being my second language, resulted in my reluctance to seek help.

I engaged in bracketing through two methods. First, I maintained a reflexive journal throughout the data collection and analysis stages, recording any thoughts, biases, beliefs, and expectations that emerged. Second, I maintained regular contact with my research supervisor, discussing my experiences and their meanings. These practices aimed to ensure that my own cognitions did not influence the VAS scores or the reflections written after the image creation sessions. These methods have been endorsed by Wall et al. (2004) and Dörfler and Stierand (2021).

Results

This study utilised an MMR design. Hence, results are reported separately for the quantitative and qualitative data, then both sets of data are triangulated.

Quantitative Results

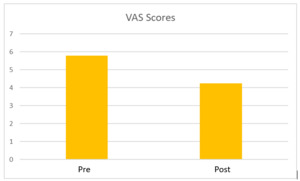

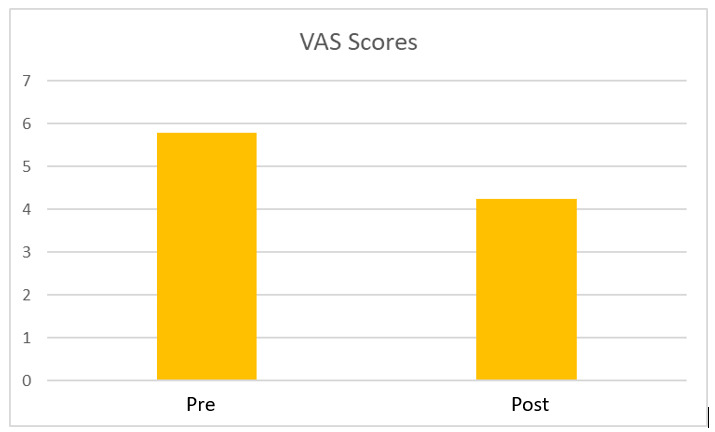

Figure 1 presents the results of a paired samples t-test analysing the difference between pre-VAS and post-VAS scores. The analysis indicates a significant effect of time, t(15) = 3.79, p < .05; post-VAS scores were significantly lower than pre-VAS scores. This suggests that the drawing and reflections effectively decreased the participant researcher’s distress over the 8-week period.

Qualitative Results

Table 1 below summarises the major themes that emerged from each intervention segment (16 in total).

Reflections became significantly more positive in the later sessions, and themes emerged such as positive mindset, self-love, self-soothing, the positive impact of drawing, and grounding. For further elaboration, Days 1, 5, 10, and 16 are discussed in detail by the participant researcher.

Day 1

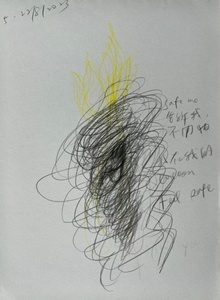

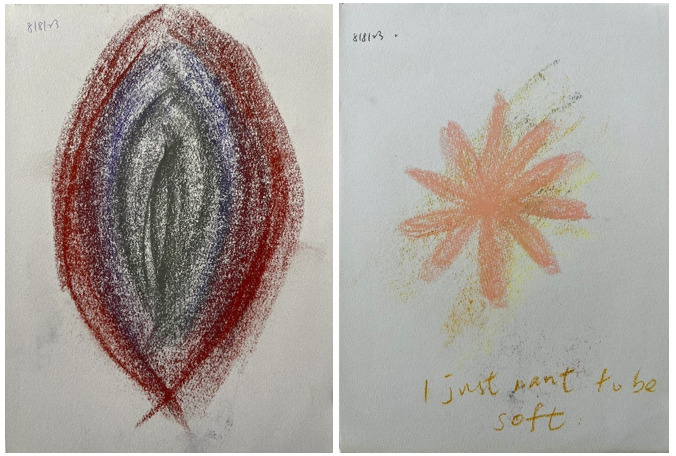

Several themes emerged on this day, including 1) soft is good, strong is not good, and 2) suffering, and wanting needs to be met. Figure 2 represents the drawing from Day 1.

Soft is Good, Strong is Not Good. While reflecting on the image, I found it overbearing and too strong, desiring it to be softer. In the transcript, I noted, “strong, but not in a soft and happy way kind of strong”.

Suffering, and Wanting Needs To Be Met. This theme emerged as I communicated with my image, exploring my feelings and what the image wanted to convey. I noticed feelings of sadness and fear, coupled with a desire to be seen. In the journal, I wrote, “I am bluffing. Because I am scared”.

Day 5

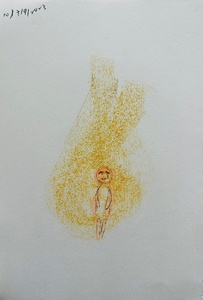

Themes that arose on this day were 1) struggling to step out of my comfort zone, 2) wanting to be seen and supported, and 3) going back to myself. Figure 3 provides the drawing from Day 5.

Struggling To Step Out of My Comfort Zone. This theme reflects my struggle to leave my cocoon. Although it felt safe inside, it was also dark, and I did not want to remain there. However, I was very tired. In my journal, I wrote, “I feel safe in my cocoon; however, there is a feeling that … can someone save me? Who do I want to rescue me?”

Wanting To Be Seen and Supported. This theme conveys my desire to be seen and feeling that life would be meaningless otherwise. I also hoped someone would reassure me that there was nothing to fear. In my transcript, I wrote, “Tell me. Don’t be afraid. There’s nothing to be scared of. Nothing is terrifying”.

Going Back to Myself. I was struggling with various issues, and I questioned why I cared so much about others. I then realised I could be the one to comfort myself and noted in my journal, “Can someone lead us …? maybe … myself … and a hug”.

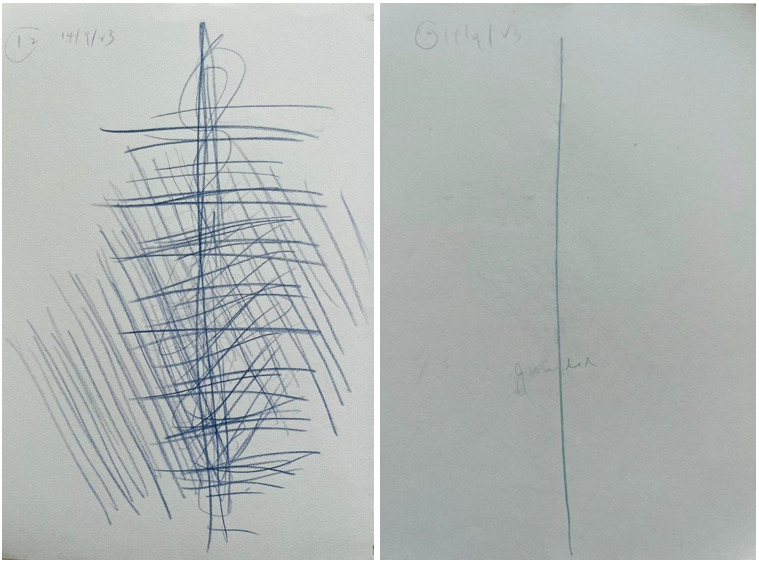

Day 10

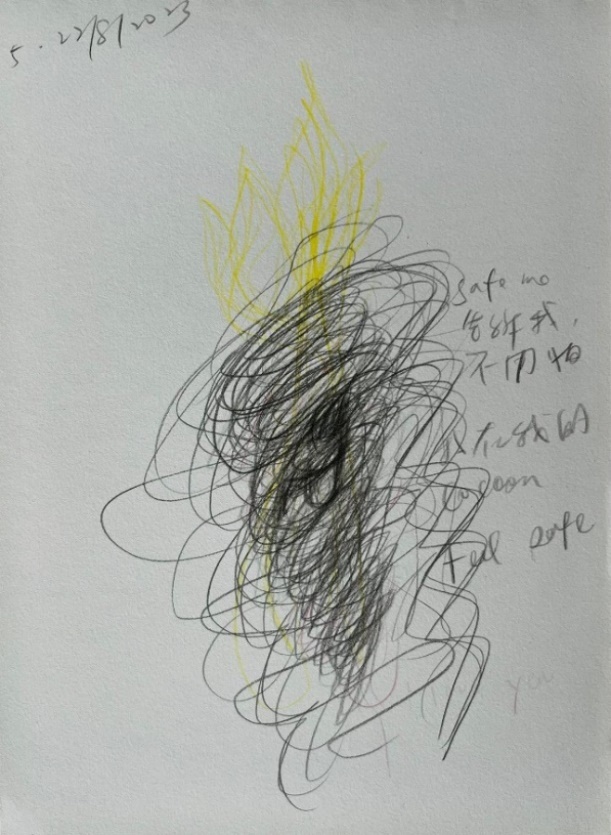

Themes that emerged on this day were 1) noticing my inner child, and 2) positive influence of self-love. Figure 4 presents the drawing from Day 10.

Noticing My Inner Child. This theme emerged when I became emotional upon noticing my inner child crying. However, I realised my inner child had become stronger. In my journal, I wrote, “I am no longer holding myself sitting on the floor anymore. I am sad, but I am standing up. Because I want to, and I can”.

Positive Influence of Self-Love. This theme emerged when I started to comfort myself by adding positive things to the image and saying affirmations. Self-love in this context involved positive self-talk, self-acceptance, and self-compassion. In my journal, I noted, “I then added the smile and the eyebrow after I said ‘you are amazing’”.

Day 16 (Last Day)

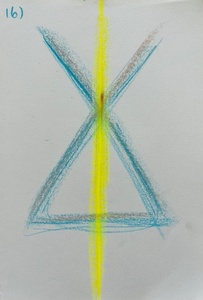

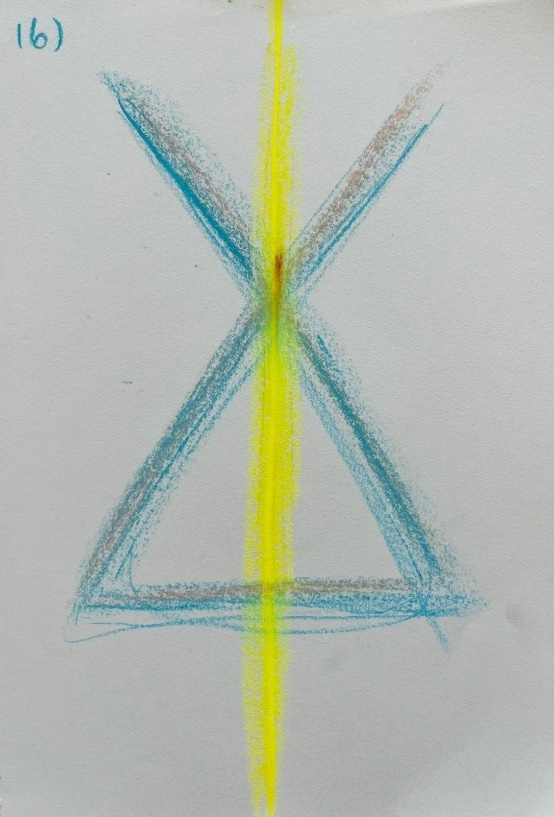

Two of the themes that emerged on this day were 1) positive meaning of drawing, and 2) positive mindset and self-love. Figure 5 shows the drawing from Day 16.

Positive Meaning of Drawing. This theme describes discovering the positive meanings of the colours, lines, shapes, and symbols in the drawing. In my journal I wrote, “And now, I just added the yellow straight line in the middle. Yellow for me is hope, bright, confidence, trust”.

Positive Mindset and Self-Love. While reflecting on the drawing, I demonstrated self-love through positive affirmations and encouraging words. I also reminded myself to be brave, strong, and faithful. I wrote, “You can do it. There’s no doubt, no fear, no nothing. You can do it. You can do anything. When you decide, not worrying, you are strong”.

Triangulation

Triangulation involves considering both streams of data side by side, searching for similarities or contradictions, and explaining these observations (Denzin, 1978). Table 2 below displays the raw qualitative and quantitative data (post-VAS scores only).

On Day 1, the post-VAS score was 7. On Day 5, it increased to 8. The themes from these two days were similar: Day 1’s theme included “suffering, and wanting needs to be met”, while Day 5’s included “struggling to step out of my comfort zone” and “wanting to be seen and supported”.

By Day 10, the post-VAS score had dropped to 0, and the themes had changed to “noticing my inner child” and “positive influence of self-love”. On Day 16, the last day of data collection, the post-VAS score was 3, significantly lower than on Days 1 and 5. The themes for Day 16 were similar to those for Day 10 and included “positive meaning of drawing” and “positive mindset and self-love”.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to assess whether engaging in art-based activities and reflecting on the process reduced the distress of an international higher education student studying in Australia. The findings demonstrated a reduction in distress levels and an increase in positive themes over time through the use of art. This suggests that reflecting on the process of art making was effective in reducing distress during the participant researcher’s international student experience in Australia.

Interpretation of Results Against the Background Literature

The current findings align with those of previous research in this area. For instance, the results support the conclusions of Davis (2010), Hsieh (2019), and Watson and Barton (2020), all of whom found that using art is effective in reducing stress and promoting wellbeing in international students.

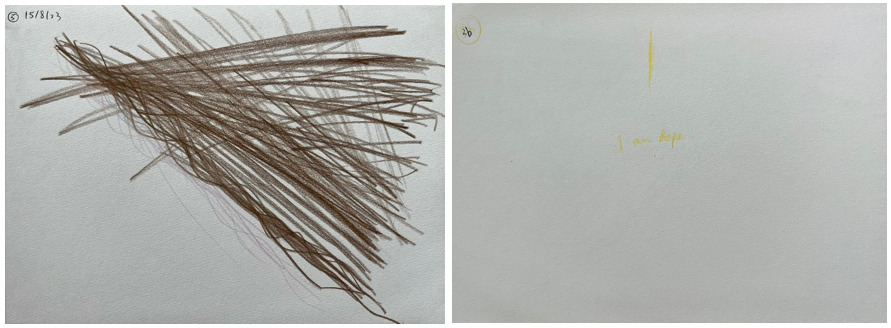

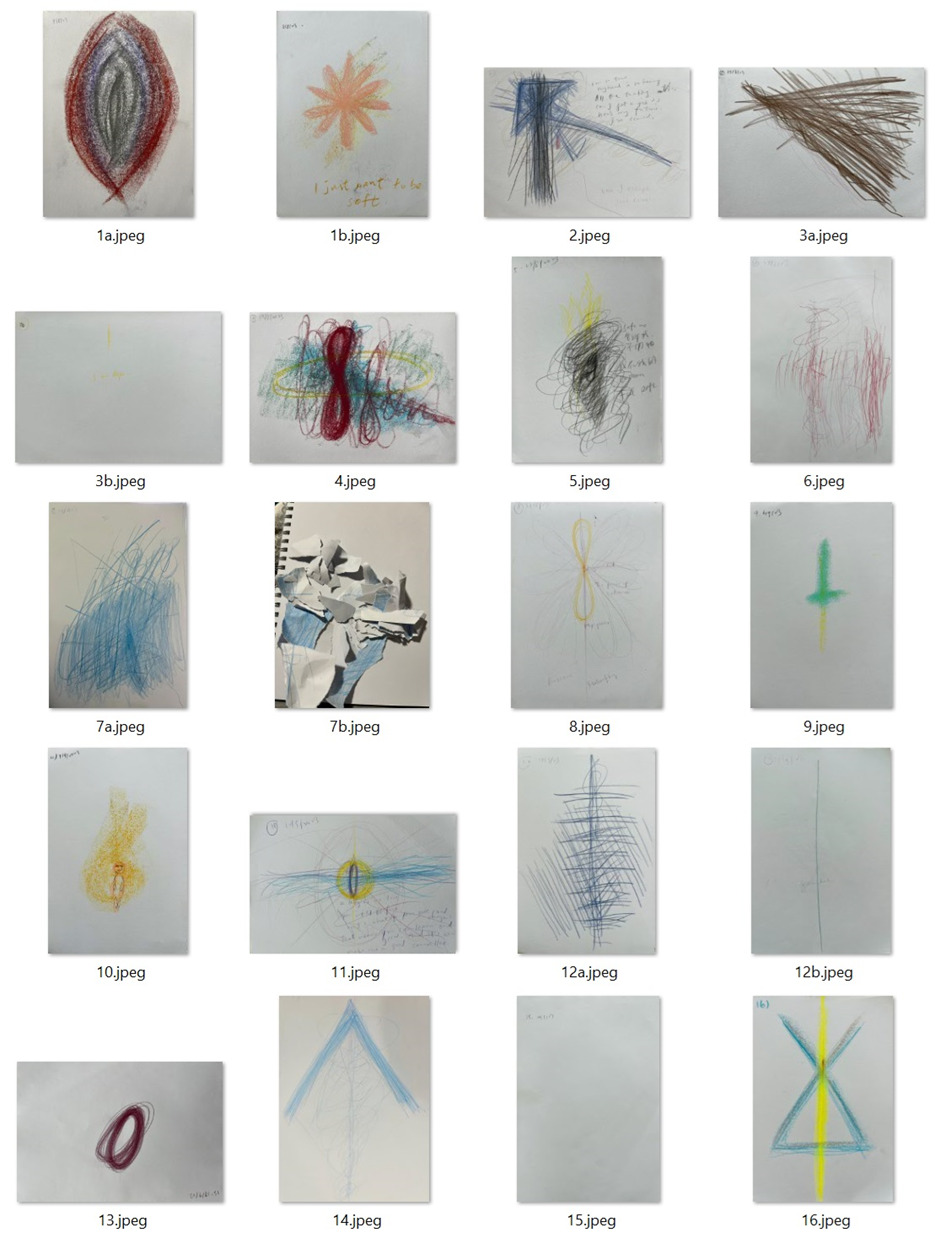

Apart from supporting the existing literature, this research revealed a new finding. The Appendix presents the entire collection of daily drawings, each numbered to indicate the corresponding day. On some days, two art pieces were created—one before reflection and another during or after. These are differentiated by appending “a” and “b” to the day numbers in the figure. For example, “1a” represents the drawing made on Day 1 before reflection, while “1b” represents the drawing made during or after reflection on the same day, which was prompted by a compelling need to create a new piece. Upon reviewing all the artwork, a noticeable shift in colour choice over time was observed. Initially, darker colours predominated, whereas lighter colours became more prevalent in later stages. Furthermore, in relation to the days featuring two artworks, such as Day 1 (see Figure 6), Day 3 (see Figure 7), and Day 12 (see Figure 8), the colour of the second piece tended to lighten after reflection. These findings suggest that stress levels influence colour selection in artwork, and that lighter hues are preferred during more positive emotional states.

Study Limitations

The current findings should be considered against the study’s limitations. First, as an autoethnographical research study, the findings are based on data from a single participant, thereby limiting their generalisability to other students. Second, the reduction in stress observed towards the final stages of data collection might have been influenced by the strengthening of peer relationships in the classroom as the semester progressed and the proximity to an upcoming semester break.

Future Recommendations

Future research in this area could seek to replicate these results using other research designs, including quasi-experimental methods. Additionally, tracking the choice of colour could provide insights into whether colour preferences change as distress is alleviated. Such insights could enable Australian universities to (1) track emotional changes by determining how students’ colour choices evolve in response to interventions or changes in their emotional state, (2) enhance support strategies by developing tailored approaches based on colour preferences, such as incorporating preferred colours in therapeutic settings, and (3) improve emotional insight by providing a non-verbal means of understanding and addressing emotional needs, which is particularly useful in contexts where students may struggle to articulate their feelings.

Research Implications

The findings of this study suggest that using expressive art coupled with reflection is effective in reducing the distress levels of an international student in Australia. Universities could consider introducing expressive art into their student support services and providing related training for student counsellors to support international students further.

Conclusion

The outcome of the reflective art-based activity undertaken in this study provides an opportunity for international students studying at Australian universities to reflect on their emotions and experiences, thereby reducing their distress. While the autoethnographic method is limited to a single person’s experience, it offers a rich data source for understanding how art can alleviate distress. Engaging in expressive art could enable individuals to reflect on their emotions and experiences, remind themselves of a positive mindset, and cultivate self-love, which could help them manage distress. Additionally, the choice of colour used by participants may reflect their distress levels. Further investigation into this area could offer more support options such as tracking emotional changes, refining support strategies, and enhancing emotional insight for international university students studying in Australia.