The World Health Organization (WHO, 2014) has recognised that violence and abuse can result in serious and enduring social and health consequences for children and young people. In New South Wales, child abuse is a criminal offence, defined under the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998 No 157 (NSW) ch 14 s 227 as physical injury, sexual abuse, or emotional or psychological harm resulting, or likely to result in, significant damage to a child or young person’s emotional, intellectual, or physical development or health. In response to the presence of child abuse, child protection systems function to protect the rights of children, prioritise children’s health and social needs, and ensure children’s safety and stability away from violence and abuse (United Nations 1989; UNICEF, 2021).

In 2022–2023, approximately one in 32 (180,000) Australian children under the age of 18 years encountered the child protection system, and 45,300 Australian children were placed in out-of-home care (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024). Out-of-home care is defined as overnight care for children who are unable to live with their families because of child safety concerns; the majority of these children are placed in home-based care comprising relative or kinship care (54%), foster care (36%), and other care arrangements (1.3%; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024). Of the 15,800 relative or kinship carer households, almost two-thirds (64% or 10,100) had one child placed with them, over one-third (35% or 5,500) had two to four children placed with them, and 1.1% (175) had five or more children placed with them (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024). It has been identified that children living in home-based care have better developmental outcomes compared with children living in staffed residential care placements (Cashmore, 2011; Department of Family & Community Services, 2015; Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020 (Council of Australian Governments, 2009) states that the problems most associated with the occurrence of child abuse and neglect are domestic and family violence, parental alcohol and drug abuse, and parental mental health problems. In response to this framework, New South Wales state-wide violence, abuse, and neglect (VAN) services have been developed; their principal responsibilities are to respond to all forms of violence and abuse within the community and provide specialist health services (New South Wales Health, 2019b). Specifically, the Child Protection Counselling Services within the VAN services provide trauma-specific counselling to children, young people, parents, and carers who experience violence and abuse (New South Wales Health, 2019a).

Literature Review

Current Diagnostic Perspectives on PTSD and C-PTSD

Experiences of violence and child abuse have been identified as increasing the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; van der Kolk, 2000). The concept of PTSD was introduced in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980), and its definition has been updated in the fourth and the current fifth editions (APA, 1994, 2013). The DSM-5 (APA, 2013) PTSD Criterion A defines a traumatic event as exposure to actual (or threatened) death, serious injury, or sexual violence, including directly experiencing, witnessing in person, learning of an occurrence, and/or repeated/extreme exposure to adverse details of a traumatic event(s). Subsequent to exposure to a traumatic event, PTSD symptom development comprises the following criteria: intrusion (Criterion B), avoidance (Criterion C), negative alternations in mood and cognition (Criterion D), and hyperarousal and reactivity (Criterion E). The symptoms must have caused significant distress or impairment for the duration of more than one month (Criteria F & G) (APA, 2013).

Similarly, the condition PTSD was first recognised by the WHO (1993) in The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, and its definition was updated in Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Requirements for ICD-11 Mental, Behavioural and Neurodevelopmental Disorders (WHO, 2024). The latter publication defines a traumatic event as exposure to an event or situation of an extremely threatening or horrific nature, such as direct experience of an event, witnessing an event, or learning about an event. The PTSD symptoms that develop subsequently are re-experiencing the event, avoidance of event reminders, and a heightened sense of threat leading to hypervigilance (WHO, 2024).

In light of these definitions, literature has emerged identifying the importance of framing PTSD to consider repeated or continuous exposure to traumatic experiences that can lead to significant attachment and interpersonal disruptions and difficulties in self-regulation (Cloitre, 2020; Friedman, 2013; Frueh et al., 2004; Jongedijk et al., 2022). In response, the ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases (WHO, 2019) introduced the term complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD). A diagnosis of C-PTSD, as well as meeting PTSD criteria, must meet the additional criteria of severe and persistent problems with affect regulation, diminished belief in oneself, and difficulty sustaining relationships as a result of prolonged or repetitive traumatic experiences.

Trauma Impacts and Treatment in Adolescents

It has been reported that children and adolescents with PTSD are likely to present with more severe trauma-related symptomology than adults, including re-experiencing, avoidance, and arousal (Gamwell et al., 2015; Linning & Kearney, 2004). A significant body of research has demonstrated that adolescents with PTSD also have higher rates of major depressive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety and mood disorders, substance abuse, and arrests (Bernet & Stein, 1999; Cauffman et al., 1998; De Bellis & Zisk, 2014; Dixon et al., 2005; Giaconia et al., 1995; Kessler et al., 2005; Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Linning & Kearney, 2004; Lipschitz et al., 2000).

Specifically, C-PTSD research indicates repeated traumatic experiences can interfere with the capacity of children and adolescents to integrate sensory, emotional, and cognitive information, often leading to prolonged stress responses, chronic avoidant strategies, interpersonal difficulties, and changes in sense of self and personal safety (Milot et al., 2016; Price-Robertson et al., 2013). Additional studies have also identified that adverse family circumstances and an increase in daily stressors have been associated with the presence and severity of trauma symptomology (Alderfer et al., 2009; Ponnamperuma & Nicolson, 2018; Schilling et al., 2007). In terms of reducing PTSD symptomology in children and adolescents, evidence-based treatments undertaken during randomised controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, prolonged exposure therapy, and narrative exposure therapy (de Arellano et al., 2014; Diehle et al., 2015; Foa et al., 2013; Ruf et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2007).

Narrative Exposure Therapy: Process and Research

First developed by Schauer et al. (2011), narrative exposure therapy (NET) is a short-term, manualised, and culturally responsive intervention for PTSD and C-PTSD. NET’s primary aim is to construct an autobiographical narrative or lifeline of both pleasant and unpleasant or traumatic experiences throughout an individual’s life (Robjant & Fazel, 2010). Once an initial lifeline has been constructed, each event is systematically retold in chronological order, focusing on traumatic events (Cooper et al., 2019; Robjant & Fazel, 2010). NET specifically focuses on treating traumatic nervous system responses and deficits in memory coding by integrating “cold” declarative aspects of traumatic memories with “hot” sensory-based aspects through a detailed and chronological re-telling of events (Elbert & Schauer, 2014; Fazel et al., 2020).

Since NET’s conception, a body of literature has emerged presenting its effectiveness in decreasing PTSD and comorbid symptoms. The literature emphasises populations exposed to multiple traumatic events, as well as low-income settings, refugees, and asylum seekers (Gwozdziewycz & Mehl-Madrona, 2013; Morina et al., 2017; Neuner et al., 2004; Nickerson et al., 2011). In relation to children and adolescents, a version termed KIDNET has been developed; three studies have indicated the positive effect of KIDNET on reducing PTSD symptoms, as well as increasing family and school functioning (Catani et al., 2009; Onyut et al., 2005; Ruf et al., 2010). Specifically, a randomised controlled trial conducted with 9–17-year-olds suffering from PTSD found that only those treated with KIDNET showed clinically significant improvement in their PTSD symptoms compared with treatment as usual (Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019).

Current Study and Ethics Statement

The current case study was conducted to understand the lived biographical narratives of an adolescent in kinship care experiencing C-PTSD and to identify clinically significant changes from pre- to post-intervention using clinical outcome measures. Signed written consent was obtained and de-identification was undertaken: all identifying information, comprising names, dates, and locations, were removed or altered for confidentiality purposes. The presented case study was reviewed by the Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee. In accordance with s 5.1.22 of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2023 (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2023) and s 5 of the Low and Negligible Risk Research Guideline (New South Wales Office of Health and Medical Research, 2023), this case study was exempt from further ethical review.

Participant: Joel

Joel was a 15-year-old male who became involved with social services owing to their significant concerns of exposure to domestic and family violence, parental mental health risk, and substance use while under the care of his parents. Joel also identified numerous experiences of community violence. Joel and his sister were removed from their parents’ care and placed in full-time kinship care with their grandparents. Joel presented with clinically significant C-PTSD, depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms (see the Outcome Measures section for further details).

Method

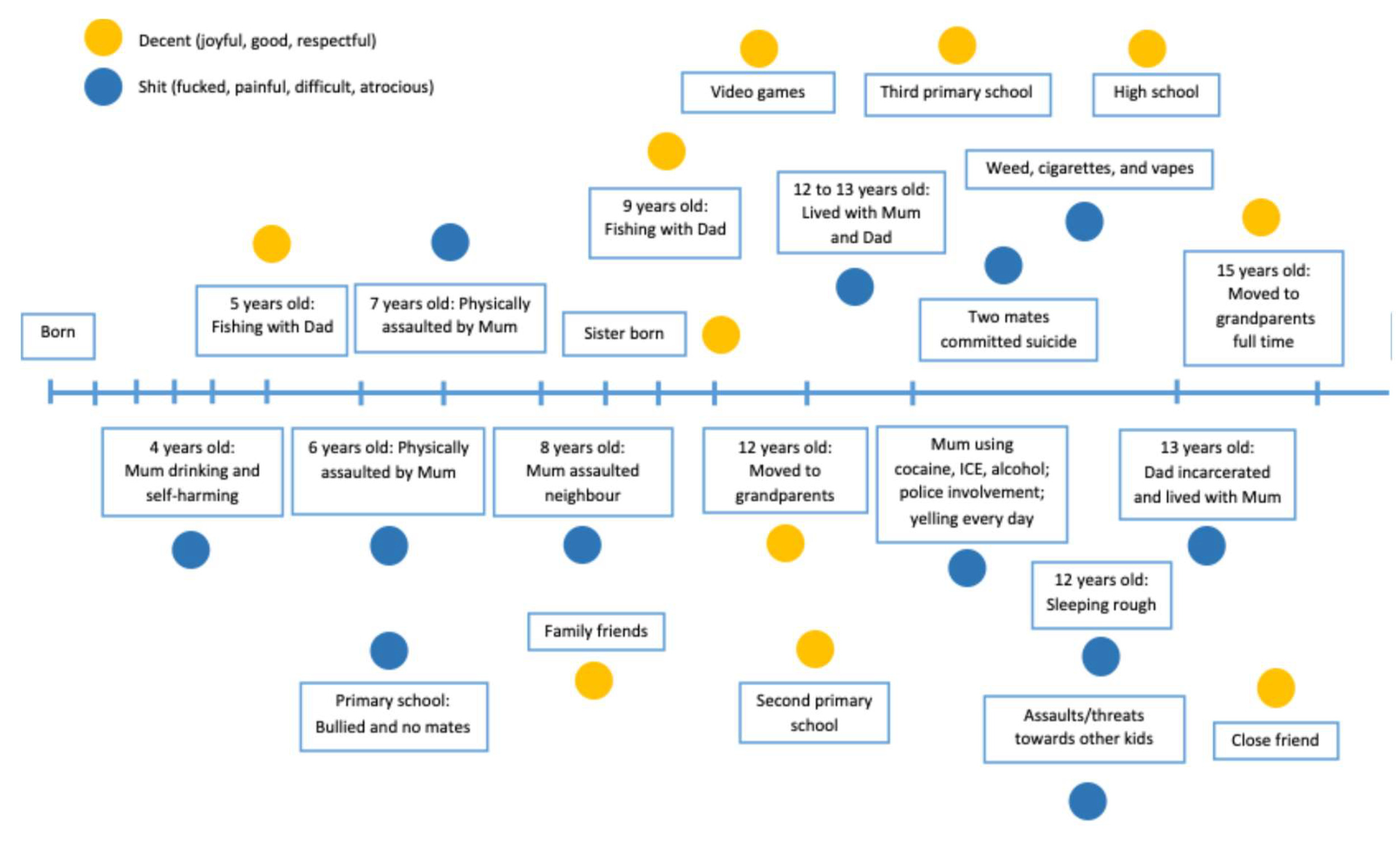

Biographical narratives

Twenty-eight KIDNET sessions were undertaken with Joel, which included the development of a lifeline (see Figure 1) and a written narrative exposition of significant events as part of the KIDNET standardised clinical procedure. Joel’s KIDNET transcripts were reviewed, and excerpts are presented in the Results section to demonstrate significant events along his biographical lifeline. The stories presented may be considered upsetting or triggering for some readers because they describe incidences of violence and self-harm and use coarse language. Please read narrative excerpts at your own discretion.

Outcome Measures

Self-report outcome measures were administered pre- and post-intervention. The outcome measures were analysed for clinical significance using standardised clinical cut-off scores for each measure.

International Trauma Questionnaire—Child and Adolescent Version (ITQ-CA)

The ITQ-CA is a 22-item self-report measure for children and adolescents aged 7–17 years focusing on the core features of PTSD, disturbances in self-organisation (DSO), and functional impairment (FI) of symptoms (Cloitre et al., 2018; Haselgruber et al., 2020).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales—Youth Version (DASS-Y)

The DASS-Y is a version of the DASS-21 for youth aged 7–18 years of age. It is designed to measure general psychological distress and the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Szabo & Lovibond, 2022).

Results

Narrative Excerpts

Substance Use

When I lived with Mum, I really started smoking weed. I would just smoke weed all day. I would probably smoke 10 or more cones a day. Sometimes up to 20. I used to sell weed from the house. Guys used to just come up to my bedroom window and buy it. I used to stay up until the sun came up. I found it quiet and peaceful watching the sunrise. I never really had a mum. The one I had was just abusive. Mums are supposed to teach you how to cook and look after you. My Mum just taught me how to pull bongs, drink alcohol, and smoke cigarettes and vapes.

Parental Mental Health and Self-Harm

Mum used to have mental breakdowns. She would drink a lot of alcohol and smoke a lot of weed. She used to break things around the house. Dad used to take us to our friends’ or grandparents’ houses when she was like this. There were times when she would cut herself. I was young at the time and didn’t really understand what I saw. But later I realised she was bleeding and had cut herself. I remember once walking into the bathroom and seeing that Mum had cut herself along her thigh with a huge knife. She would often have cuts up along her arms. I remember one day I got home, and Dad was waiting out the front. My sister was already in the car. I asked him what was going on, and he said Mum was trashing and breaking stuff in the house. He said to go in and put some clothes in a bag and he will drop us off at our grandparents’ house.

Parental Assault

Sometimes I would stay up all night just to make sure Mum didn’t hurt me or my sister. Mum would physically hit me. She has hit me with a pole, a baseball bat, a fry pan, and with her fists and hands. She burned me with a lighter. I remember there was one night Mum was there, really drunk and had smoked ice. She came in and just started hitting me. I tried to protect myself and I hit her back. I remember packing my things into a bag. I got my school stuff and left the house.

Community Violence

Two friends and I got in a fight with three older boys. We met on the corner of the street not far from our house. We started hitting and punching each other. One of my friends ended up pulling out a flick knife and cut one of the other boys on the neck. I remember him holding his neck and blood coming through his fingers. I remember I didn’t want anything to do with a stabbing. I took off home. Dad asked what happened to me, and I said that I got in a fight.

Community Violence at School

There is a rule at school and out in the community that “if you drop the bag, it’s on”. What this means is that if you drop your bag intentionally in front of someone then you want to fight them. I remember when I was at primary school a kid had talked shit about my Mum, saying she was a druggy. I dropped my bag in front of him and we had a fight. I remember really hurting him during the fight. He came back a day or two later and apologised for saying shit about my Mum. Not long after, his younger brother dropped his bag in front of me and we had a fight. I remember punching into him and knocking him out. I remember my friend was there and saw it and got quite scared. Around this time, I got in trouble with the police as well. I have been charged with assault, vandalism, and property damage. In looking back at this time in my life, at the time I didn’t really feel bad about it or regret it. But now I look back and feel bad about it. I know now there is a better life and better way to deal with things. I haven’t been in a fight now since for about two years.

Sleeping Rough

There was a place me and friends used to hang out at called The Sewers. Kids shouldn’t grow up in The Sewers. I would leave home and stay overnight in The Sewers a lot when I was left home alone with Mum. I would stay there overnight and go to school the next day. I remember I used to go to the shops and steal food and drinks. Some of the kids at school used to call me a “monster”. My friends knew what was going on, as they would see me at school pretty rough. During this time, I became a ghost. I lost my childhood. I lost my emotions and feeling anything. I was just surviving.

Freedom

When I was living with Mum, there were days where we would have no food at all. Sometimes, there was [sic] whole weeks when we had no food in the home. We would just be hungry all the time. We’re not hungry anymore. I would always wear my headphones with one side off. This way, I knew if she would be coming in. I would also be able to hear if the police were there. The difference now living with my grandparents is that I can actually put both headphones on each side. I don’t feel worried that something is going to happen all the time. I feel free now that I live with my grandparents. It is weird that they have rules, but I feel freer. There is the respect from both of us. There wasn’t much respect at the beginning, but now we have figured it out. These days I shower every day, I have food, I get to school, I have my own room and my own space to do what I want. It feels freer. I actually give a fuck now. I give a fuck about myself. I give a fuck about my family. I give a fuck about school. I am no longer just focused on surviving. It feels like Nan and Pop have that covered. I am free to focus on what I want to do.

Outcome Measures

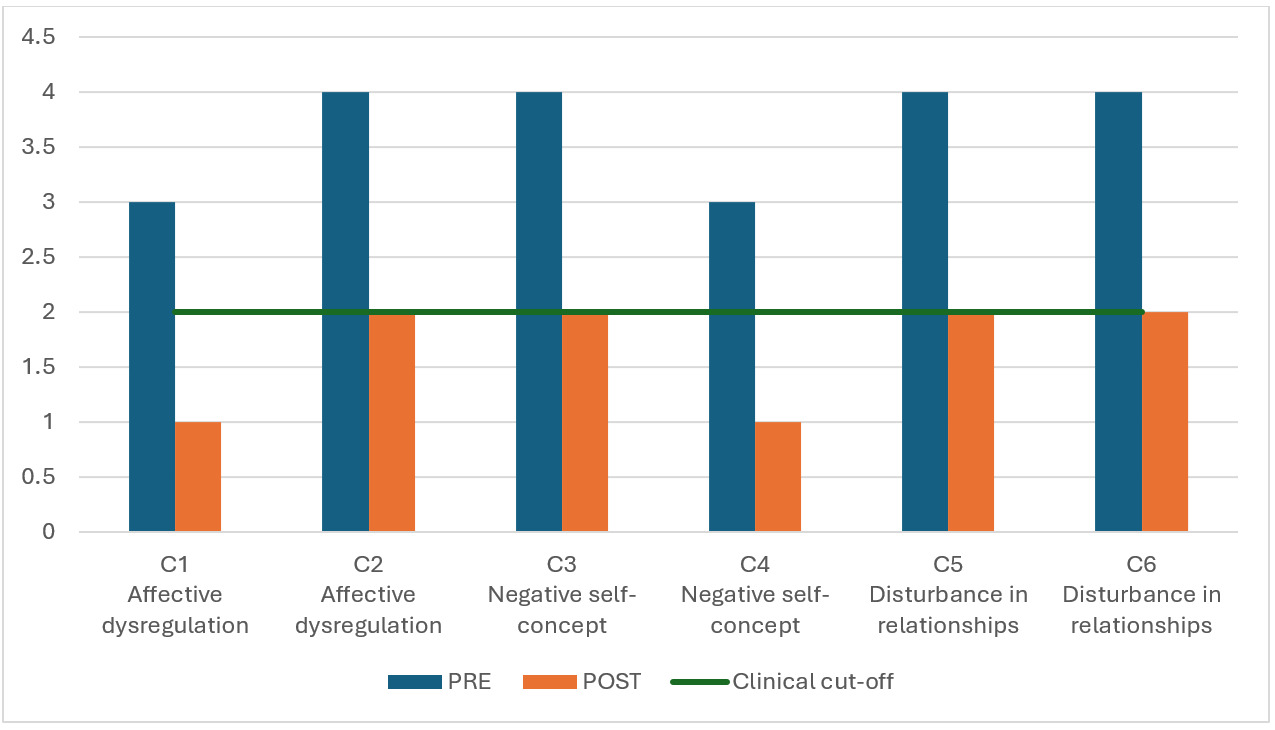

ITQ-CA

The ITQ-CA PTSD categories comprise re-experiencing (items P1–P2), avoidance (items P3–P4), and a sense of threat (items P5–P6). DSO categories comprise affective dysregulation (items C1–C2), negative self-concept (items C3–C4), and disturbances in relationships (items C5–C6). FI is assessed for both PTSD and DSO across friends, family, school, and other categories (items P7–P10, C7–C10).

Changes in PTSD Symptoms

Joel’s PTSD pre- to post-intervention scores on re-experiencing (P2) and avoidance (P3) decreased from above to below the clinical cut-off score. Sense of threat (P5) decreased but remained on the clinical endorsement cut-off score. Re-experiencing (P1) scored zero on both pre- to post-intervention measures and as a result has not been included (see Table 1).

Joel’s PTSD FI scores pre- to post-intervention showed a decrease but remained on the clinical endorsement cut-off in relation to family. The FI scores remained on the clinical endorsement cut-off in relation to school and general happiness. FI items P7 (friends) and P10 (other) scored zero on both pre- to post-intervention measures and as a result have not been included.

PTSD diagnosis requires a score of ≥ 2 (“moderately”) for one symptom in each PTSD category and a score of ≥ 1 (“a little bit”) for one FI item (Haselgruber et al., 2020). Joel’s PTSD pre- to post-intervention scores indicated a clinically significant decrease from pre-intervention scores meeting the clinical cut-off for PTSD to post-intervention scores no longer meeting the cut-off for PTSD.

Changes in DSO Symptoms

Joel’s scores for affective dysregulation (C1) and negative self-concept (C4) decreased from above to below the clinical endorsement cut-off. Additionally, affective dysregulation (C2), negative self-concept (C3), and disturbances in relationships (C5-C6) decreased from above to on the clinical endorsement cut-off (see Table 2).

Joel’s DSO FI scores pre- to post-intervention showed a decrease from above to below the clinical endorsement cut-off in relation to friends (C7), family (C8), and other (C10) but remained on the clinical endorsement cut-off in relation to school (C9) and general happiness (C11). In addition to meeting PTSD criteria, C-PTSD diagnosis requires a score of ≥ 2 (“moderately”) for one symptom in each DSO category and a score of ≥ 1 (“a little bit”) for one FI item (Haselgruber et al., 2020). Joel’s DSO pre- to post-intervention scores indicated a clinically significant decrease from pre-intervention scores meeting the clinical cut-off for C-PTSD to post-intervention scores no longer meeting the cut-off for C-PTSD.

DASS-Y

Joel’s DASS-Y scores pre- to post-intervention demonstrated a decrease over the three categories of depression, anxiety, and stress. Specifically, Joel’s scores for depression decreased from the extremely severe to the moderate clinical category, anxiety decreased from the extremely severe to the average clinical category, and stress decreased from the extremely severe to the mild clinical category (see Table 3).

Discussion

The presence and impacts of violence, abuse, and neglect in the context of Australian children in kinship care is an ongoing concern for health services. For example, approximately 45,300 Australian children were placed in out-of-home care in 2022–2023 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024). It has been reported that children and adolescents who have experienced violence, abuse, and neglect are likely to present with severe trauma-related symptoms, including both PTSD and C-PTSD symptomology as well as comorbid symptoms of depression, anxiety, and substance use (De Bellis & Zisk, 2014; Gamwell et al., 2015; Milot et al., 2016; Ponnamperuma & Nicolson, 2018).

In the current study exploring the lived biographical narratives of an adolescent in kinship care who was experiencing C-PTSD, NET was administered and extracts from the transcripts were thematically presented. Themes included substance use, parental mental health and self-harm, parental assault, community violence, sleeping rough, and freedom. These themes are in line with previous research reported in the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020 (Council of Australian Governments, 2009), which outlines domestic and family violence, parental substance abuse, and parental mental health problems as the primary difficulties associated with child abuse and neglect. Additionally, themes presented support the Australian Institute of Family Studies (2022) report, which found that owing to past traumatic experiences children and adolescents in out-of-home care are at increased risk of emotional and behavioural issues, attachment disruptions, and instability in caregiving environments.

The case study excerpts demonstrated the lived biographical narratives of Joel, an adolescent in kinship care who had presented with C-PTSD. The narrative excerpts highlight a range of adversities experienced by Joel. Specifically, both personal and parental substance use was identified, in addition to selling substances, thereby highlighting the impact of use on the parent–child relationship. The significant impact of parental mental health was exemplified through Joel’s numerous experiences of parental assault with an implement and witnessing repeated parental self-harm. Community violence in public and at school were described, including the use of weapons and family- or honour-based altercations. Joel also described sleeping rough, needing to steal for food, and losing his childhood due to “just surviving”. Despite these challenges, Joel reflected on his experience of freedom, including an increased sense of safety, respect, self-confidence, and connection.

The current study also aimed to identify clinically significant changes from pre- to post-intervention. The ITQ-CA and the DASS-Y were used as pre- and post-outcome measures. ITQ-CA scores indicate a clinically significant decrease from above to below the PTSD and C-PTSD clinical cut-off scores. Results indicate clinically significant decreases on all subscales, except disturbances in relationships. These results provide preliminary support for NET as an effective treatment for adolescents in kinship care and highlight the need for additional social- or interpersonal-based interventions. DASS-Y scores indicate clinically significant decreases along all three categories of depression, anxiety, and stress. These results demonstrate support for the use of NET with adolescents in kinship care and its effectiveness not only for trauma-related symptoms but also depression, anxiety, and stress.

Limitations and Future Research

Limitations of the study include a small sample, which restricted generalisability, and the lack of a comparative control sample. Future investigations should consider a larger case series and use of a waitlist or treatment-as-usual control group for statistical analysis. Additionally, the data presented were specifically drawn from an adolescent’s lived experiences, while little attention was given to the experiences of other important people in his life. Future investigations could include feedback or reflections from caregivers, teachers, and other community members. This feedback could include measuring changes observed in carer–child relationships and family functioning.

Conclusion

From a clinical perspective, therapists and clinicians should screen and treat for PTSD or C-PTSD among adolescents in kinship care. Therapists and clinicians should also be aware of the high severity and repetitive exposure to trauma that adolescents in kinship care experience. Finally, it is recommended that trauma-focused interventions such as NET be incorporated into out-of-home care services to support adolescents who have experienced violence, abuse, and neglect.