Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder historically believed to occur predominantly in childhood followed by symptom reduction throughout adolescence and into adulthood (Asherson & Agnew-Blais, 2019; Song et al., 2021). However, ADHD is now recognised as a condition that persists into adulthood (Faheem et al., 2022; Ginsberg et al., 2014), and diagnostic rates of ADHD in adulthood are increasing (C. L. Huang et al., 2020; Paul et al., 2025). Women between the ages of 23 and 49 represent the group with the greatest increase in ADHD diagnoses in the period 2020–2022 (Russell et al., 2023). While boys are 2–2.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than girls (Mowlem et al., 2018), this disparity may be less pronounced than previous estimates have suggested (Faheem et al., 2022) and could be influenced by lack of recognition and/or referral bias related to girls (Young et al., 2020). Misconceptions that contribute to missed diagnoses of ADHD in girls and women include stereotypes of ADHD not reflecting female presentations and the tendency for girls to be highly proficient at masking the condition (Craddock, 2024). Recent trends suggest that, although persistent, these misconceptions about ADHD in girls and women are becoming less pronounced since gender disparities in adult diagnoses dramatically decreased in the period 2010–2022 (Russell et al., 2023).

ADHD in Women

Consistent with the observed increase in adult diagnoses of ADHD in women, several recent studies have investigated the impact of ADHD in women and girls, although a significant data gap remains (Hinshaw et al., 2022). Research has found that women with ADHD are more likely than men to receive a delayed diagnosis of ADHD and to experience a range of negative outcomes associated with ADHD (Hinshaw, 2018). For example, women with ADHD are at elevated risk of a range of psychosocial and physical comorbidities (Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016), including, but not limited to, mood disorders and substance use disorders (Hartman et al., 2023), work-related disabilities, teen motherhood, and non-suicidal self-harm and suicide attempts (Hinshaw et al., 2022). Women with a late diagnosis of ADHD report significant challenges across all domains of life, which affect their physical, psychological, social, educational and financial wellbeing. Of particular note is the negative impact of undiagnosed ADHD on an individual’s sense of self, whereby some women report trauma-related symptomology, such as a disturbed sense of self, lack of trust in self and others, and the use of maladaptive coping strategies (Witteveen & O’Hara, 2025). These findings not only indicate that late diagnosis of ADHD in women is highly consequential but also highlight the importance of understanding the sociocognitive mechanisms by which these negative outcomes may occur, and how they may be mitigated within a therapeutic context.

Of particular interest is the recognition that adults with ADHD can experience challenges with social cognition (Bora & Pantelis, 2016) and emotional dysregulation (Shaw et al., 2016), which are associated with impaired self-regulation capacities (Badoud et al., 2018). Specifically, difficulties with mentalisation have been found to affect interpersonal functioning (Perroud et al., 2017) and may be implicated in negative psychosocial outcomes that persist, even when other symptoms have responded to medication (Brown et al., 2017). Conversely, self-compassion has been identified as a protective factor for a range of clinical populations, including ADHD (Beaton et al., 2022). Since individuals with ADHD report frequent experiences of criticism (Beaton et al., 2020) and negative self-perceptions (Craddock, 2024), the potential for self-compassion to be a mediator of negative impacts in this population represents an important consideration. Therefore, mentalisation represents a potential predictor and self-compassion represents a potential mediator of negative psychosocial outcomes for women with ADHD.

Mentalisation as a Predictor of Psychosocial Impact

Bateman and Fonagy (2019) defined mentalisation as “an individual’s awareness of mental states in himself or herself and in other people, particularly in explaining their actions. It involves perceiving and interpreting the feelings, thoughts, beliefs, and wishes that explain what people do” (p. 3). Mentalisation thus requires the capacity to attend to internal and external cues, as well as an awareness of oneself in relation to others (Fonagy & Bateman, 2006), and is reliant upon attentional control and emotion regulation skills, which are known to be areas of challenge for individuals with ADHD (Hinshaw et al., 2022).

Difficulties with mentalisation were originally identified in individuals with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD; Volkert et al., 2019), and these challenges have also been identified in adults with ADHD (Badoud et al., 2018). For individuals with BPD and ADHD, poor mentalisation is associated with higher symptomology and increased difficulties with emotion regulation and interpersonal functioning (Perroud et al., 2017). Mentalisation-based treatments have been found effective in reducing symptoms in individuals with a diagnosis of BPD and a range of comorbid conditions (Volkert et al., 2019), and there is emerging evidence to suggest that mentalisation could represent a meaningful change mechanism for people with ADHD (Badoud et al., 2018). This may be particularly relevant for women with ADHD, given that the samples included in many of the mentalisation-based intervention studies have comprised mostly female participants (see, for example, Badoud et al., 2018, and Volkert et al., 2019, for more detail).

Despite replication in multiple studies of robust associations between mentalisation and psychosocial outcomes (Bateman & Fonagy, 2019) and the promising findings pertaining to mentalisation-based therapy approaches (Volkert et al., 2019), the early assessment of mentalisation has been identified as “fraught”, and many studies have assessed mentalisation via related constructs, such as reflective functioning (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018, p. 269). Consistent with observations of the need for a more robust measurement instrument for mentalisation, a psychometrically validated measure, namely, the Mentalisation Scale (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018), was developed and subsequently validated in a number of languages, and in community and clinical samples (Stefana et al., 2024). The structure of that measure comprises three separate factors—self-related mentalisation, other-related mentalisation, and motivation to mentalise—indicating that the construct of mentalisation may be appropriately considered a constellation of related yet distinct cognitive capacities (Luyten et al., 2020). Moreover, the identification of these factors highlighted that, in addition to the clinical relevance of mentalisation as a general construct (Richter et al., 2021), evaluating individual aspects of mentalisation may further clarify the relationship between mentalisation and negative psychosocial outcomes (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018).

Consistent with this implication, Dimitrijevic et al. (2018) reported that total scores on the Mentalisation Scale and on the Self-Related Mentalisation sub-scale were significantly different between a clinical (BPD) and control sample, with scores on the Self-Related Mentalisation sub-scale the most effective differentiator between those groups. Further, when attachment styles were compared, significant differences in scores on the Mentalisation Scale and its sub-scales were also identified between groups, and the Self-Related Mentalisation sub-scale again demonstrated the greatest differentiation among the groups (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018). These findings further support the potential clinical and research benefits of exploring the relative contributions of different aspects of mentalisation to psychosocial outcomes in clinical populations (Richter et al., 2021). In particular, the patterns of scores obtained from previous clinical samples suggest that self-related mentalisation may be particularly influential in the negative psychosocial outcomes associated with a range of psychiatric diagnoses, including ADHD (Perroud et al., 2017; Richter et al., 2021). Despite a growing interest in the role of mentalisation in ADHD (Badoud et al., 2018; M. Huang & Hou, 2023; Perroud et al., 2017), the unique impact of self-related mentalisation has not been investigated in an ADHD sample, and this gap contributed to the development of the current study.

Self-Compassion as a Mediator of Psychosocial Impact

While difficulties with mentalisation appear to be implicated in negative psychosocial outcomes (Bateman & Fonagy, 2019), a substantial body of literature has identified that self-compassion, which comprises self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (Neff, 2003), represents a mechanism of resilience and serves as a protective factor (Inwood & Ferrari, 2018). It has been suggested that self-compassion may be of particular relevance for individuals with ADHD, who receive more frequent negative feedback and are prone to high levels of self-criticism and shame than their age-matched peers (Beaton et al., 2020). Consistent with this proposition, self-compassion has been found to mediate between ADHD and psychosocial outcomes, and the potential therapeutic benefits of self-compassion interventions in this population have been noted (Beaton et al., 2022). Of particular interest to the current study is the finding that both mentalisation and self-compassion may have particular clinical relevance to adolescents with ADHD (M. Huang & Hou, 2023). However, this relationship has not specifically been investigated in adults or women with ADHD, an observation that further informed the development of this study.

The Current Study

Given the need for better understanding of the risk and protective sociocognitive factors contributing to psychosocial outcomes experienced by women with ADHD, the purpose of the current study was to develop a brief measure of ADHD psychosocial impact and to explore the relationships between mentalisation, self-compassion, and ADHD impact. Phase 1 established a preliminarily validated tool for assessing the impact of ADHD on psychosocial functioning, laying the foundation for Phase 2 to explore how mentalisation and self-compassion relate to these outcomes.

Phase 1: ADHD Impact on Psychosocial Functioning (AIPF) Validation Analysis

In the course of the current study, the need for a brief, freely available measure of the impact of ADHD on psychosocial functioning was identified, since previously validated measures tend to serve as screening tools prior to diagnosis (e.g., the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; Kessler et al., 2005), focus more broadly on quality of life (e.g., Adult ADHD Quality of Life Scale; Brod et al., 2006), or require licensing for use (e.g., ADHD Impact Module—Adult™; Landgraf, 2007). Therefore, the purpose of this phase of the study was to develop and conduct a preliminary validation of a brief measure—the ADHD Impact on Psychosocial Functioning (AIPF)—that assesses the impact of previously diagnosed ADHD across psychosocial domains that have been identified as particularly affected by the social cognition and emotion regulation challenges associated with ADHD (Badoud et al., 2018).

Phase 1: Method

Participants

Three hundred and eighty-eight women who had received a diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood participated in Phase 1 of the study. The age at which participants had received their ADHD diagnosis ranged from 18 to 72 years (M = 41.28; SD = 10.48), and their age at the time of participation ranged from 19 to 73 years (M = 43.95; SD = 10.47). Time since receiving a diagnosis of ADHD ranged from 0 to 20 years (M = 2.70, SD = 2.55), and the majority of participants (91.5%) had received their diagnosis within the previous 5 years. The demographic details of participants, namely, level of education, ADHD subtype, and other psychiatric diagnoses, are provided in Table 1.

The demographic information presented in Table 1 indicates that this sample differs from those in previous studies in terms of educational attainment and the type of ADHD diagnosis most commonly received, while the high levels of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses reported are generally consistent with those reported in previous research. Specifically, the high proportion of participants who had completed tertiary qualifications (62.3%) contrasts with previous studies, which have indicated women with ADHD may experience significant barriers to educational attainment (Owens et al., 2017), particularly at the tertiary level (Morley & Tyrrell, 2023). Further, this proportion of participants with tertiary qualifications differs from estimates of educational attainment of age- and gender-matched counterparts in the general population, whereby the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that in 2024 37% of women aged 15–74 years in Australia held a bachelor degree or above. In addition, the high percentage of participants reporting a combined ADHD diagnosis in this study (56.4%) contrasts with previous research, which has consistently indicated that women are more likely to be diagnosed with inattentive type ADHD (Williams et al., 2023).

Conversely, the high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, particularly anxiety (72.3%) and depression (53.2%), is consistent with a substantial body of literature that has reported that women with ADHD commonly receive comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016), and at higher prevalence rates than women who do not have a diagnosis of ADHD (Hartman et al., 2023). Although this group reported lower levels of comorbid autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than in other studies (i.e., 15.2% in the current study compared with 50–70% reported by Rong et al., 2021), a number of participants indicated that they suspected they may also have ASD but had not yet been assessed for that condition. Common reasons for this included the recency of their ADHD diagnosis, which was the first time that ASD had been mentioned to them, and the financial costs associated with ASD assessments. Hence, it is possible that the reported rate of ASD comorbidity is an underestimate of the true comorbidity of ADHD and ASD in this sample.

Measures

ADHD Impact on Psychosocial Functioning

Qualitative studies and review studies that have explored the experiences of women diagnosed with ADHD have identified a range of psychosocial domains that are affected by this diagnosis (Attoe & Climie, 2023; Morley & Tyrrell, 2023; Owens et al., 2017). These domains comprise self-confidence, self-esteem, emotional wellbeing, emotion regulation, work, career, intimate relationships, and other significant relationships. Consistent with these studies, a series of 8 items was developed on a Likert scale on which 0 = This is not at all true for me and 5 = This is very true for me. These items were the subject of this validation study, and are presented in Table 2.

Satisfaction with Life Scale

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) is a 5-item scale that measures overall life satisfaction. Items are scored on a Likert scale on which 1 = Strongly disagree and 7 = Strongly agree. The minimum score is 5 and the maximum score is 35, and higher scores indicate higher levels of life satisfaction. The internal consistency estimates of this measure are good; the original validation study reported α = .87 (Diener et al., 1985). This measure was utilised as a measure of discriminant validity in this study.

Procedure

This study received ethics approval from the University of Queensland’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 2023/HE002187). It was initially advertised on the university’s research website and then broadcast on national radio programs and in print articles across a number of Australian media outlets. Women who had received an adult diagnosis of ADHD were invited to complete an expression of interest, upon submission of which they were provided with information about this study, and invited to contact the researchers via email for additional information prior to providing consent. If requested, one of the researchers contacted participants via telephone to provide additional information. All other queries were responded to via email. After providing informed consent, participants completed a series of online questionnaires via Qualtrics. Participants were able to complete the questionnaires in multiple attempts, if required. All participants completed the survey in the same order, namely, a demographic questionnaire, a series of questions pertaining to the way/s in which they perceived ADHD affected various aspects of their psychosocial functioning, and questions comprising the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985). An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the items assessing the impact of ADHD on psychosocial functioning, using principal component analysis (PCA) with direct oblimin rotation. Reliability estimates and discriminant validity checks were then undertaken to ascertain the utility of these items as a measure of the psychosocial impact of ADHD.

Phase 1: Results

PCA

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was highly significant at χ2(28) = 1,265.4, p < .001, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was .81, which indicated the data and sample were “meritorious” for factor analysis (Sarstedt & Mooi, 2019). Two components were identified with eigenvalues > 1 (3.87; 1.17), which cumulatively explained 62.92% of the variance, and h2 was > .5 for all items. The first component explained 48.36% of the variance and the second component explained a further 14.6% of the variance. Each component had four items that had loadings of > .5, which exceeded the recommended minimum loading for this sample size of .298, as set out by Stevens (2002, as cited in Field, 2013). Table 2 provides the items and their respective loadings on each component, as identified in the pattern matrix.

An examination of the components and their respective items indicated that Component 1 assessed the impact of ADHD on internal domains, namely self-esteem, emotion regulation, confidence, and emotional wellbeing, whereas Component 2 represented a measure of the impact of ADHD on external domains, including work, career, and intimate and other significant relationships.

Reliability Analyses

Reliability analysis of this measure indicated good internal consistency: α = .84 and item-total correlations ranging from .43 to .68. There were no notable changes in the measure’s reliability with the deletion of any items. Sub-scale estimates of internal consistency were α = .84 for internal impact and α =.74 for external impact, which suggested both sub-scales were sufficiently reliable at this early stage of development (Nunnally, 1978, as cited in Cheung et al., 2024).

Construct Validity

An initial evaluation of the discriminant validity of this measure was conducted by correlating scores on the sub-scales and total measure with scores on the SWLS. As expected, all scores derived from the AIPF were negatively correlated with scores on the SWLS (external sub-scale r = −.38, p < .001; internal sub-scale r = −.24, p < .001; total score r = −.36, p < .001), and the external sub-scale correlated most strongly. This pattern of correlations provided preliminary support for the discriminant validity of the AIPF in this initial sample.

Phase 1: Brief Discussion

In Phase 1 of this study, a brief measure of the impact of ADHD on a range of psychosocial outcomes was developed, and an initial evaluation of its properties was conducted. Eight items with high face and content validity were generated from previous research and a PCA was conducted. The data were found to be suitable for PCA, as indicated by Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity and the KMO sampling adequacy measure. Two components with eigenvalues > 1 emerged and accounted for 62.92% of the variance; four items loaded strongly on each component. The first component assessed the impact of ADHD on the internal domains of self-esteem, emotion regulation, confidence, and emotional wellbeing, while the second component assessed the impact of ADHD on the external domains of education, career, and relationships. Reliability analyses indicated satisfactory internal consistency for both sub-scales and the overall measure, and a preliminary examination of the discriminant validity of this measure, with reference to a measure of satisfaction with life, was consistent with expectations.

Taken together, these findings suggest the AIPF may be appropriate for use as a brief instrument to gauge the impact of ADHD on psychosocial functioning. While preliminary findings suggest strong reliability and discriminant validity, further validation, particularly in construct validity and test-retest reliability, is required. Additionally, examining the AIPF’s applicability across different ADHD populations (e.g., men, adolescents) is essential to establish broader utility. Despite these limitations, initial validation supported the AIPF’s inclusion in Phase 2, where its applicability to broader psychosocial contexts was further examined. Additional limitations of this phase of the study and the implications of its findings are discussed in more detail in the General Discussion which follows Phase 2.

Phase 2: Mentalisation, Self-Compassion, and the AIPF

The properties of the AIPF were deemed suitable for use with a sample of women with a diagnosis of ADHD. Accordingly, the second phase of this study aimed to investigate the relationships between mentalisation, self-compassion, and the impact of ADHD on psychosocial functioning. It was hypothesised that self-related mentalisation and self-compassion would be predictive of the psychosocial impact of ADHD. Specifically, low self-related mentalisation was hypothesised to predict higher psychosocial impact of ADHD, and higher self-compassion was hypothesised to predict lower psychosocial impact of ADHD. Given previous findings that suggest self-compassion may serve as a protective factor against negative mental health outcomes (Beaton et al., 2020; Inwood & Ferrari, 2018), it was further hypothesised that self-compassion would mediate the predictive relationship between self-mentalisation and ADHD impact.

Phase 2: Method

Participants

Eighty-nine women who had received a diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood participated in this study. The age at which participants had received their ADHD diagnosis ranged from 23 to 64 years (M = 39.72; SD = 9.11), and their age at the time of participation ranged from 24 to 65 years (M = 42.33; SD = 9.3). Time since receiving a diagnosis of ADHD ranged from 0 to 19 years (M = 2.62, SD = 2.90), and the majority of participants (94.4%) had received their diagnosis within the previous 5 years. The demographic details of participants, namely, level of education, ADHD diagnosis, and other psychiatric diagnoses, are provided in Table 3.

As with the first phase of this study, the demographic profile of participants suggests a greater proportion had completed tertiary qualifications and received a diagnosis of combined type ADHD than has been reported in previous studies, while the rates of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses were comparable to other estimates. Independent samples t-tests revealed no significant differences in age (t = −.1.336, df = 475, p = .18), and chi square tests revealed no significant differences in education, X2 (2, 434) = 3.1, p = .21, and ADHD diagnosis, X2 (9, 422) = 15.03, p = .09, between participants who participated in Phase 1 and Phase 2 of this study.

Measures

The Mentalisation Scale

The Mentalisation Scale (MentS; Dimitrijevic et al., 2018) is a 28-item questionnaire that measures mentalisation on three sub-scales, namely, Self-Related Mentalisation (MentS-S; 8 items), Other-Related Mentalisation (MentS-O; 10 items), and Motivation to Mentalise (MentS-M; 10 items). Each item is scored on a Likert scale on which 1 = Completely incorrect and 5 = Completely correct. Total scores on the MentS-S range from 8 to 40, scores on the MentS-O and MentS-M range from 10 to 50, and scores on the overall measure range from 28 to 140. Higher scores suggest greater ability to understand thoughts, feelings, and intentions in oneself and others, which is indicative of capacity for reflective functioning and social and emotional awareness (Cosenza et al., 2024; Stefana et al., 2024). The internal consistency of each of the sub-scales was reported as acceptable (MentS-S α = .77; MentS-O α = .77; MentS-M α = .76) and the internal consistency of the total scale was reported as good (MentS α = .84) in the original validation study of this measure (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018) and these findings have been replicated in additional studies (Cosenza et al., 2024; Stefana et al., 2024).

Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form

The Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF; Raes et al., 2011) is a 12-item scale that assesses an individual’s tendency to engage in self-compassion. Each item is scored on a Likert scale on which 1 = Almost never and 5 = Almost always. The SCS-SF comprises six sub-scales, three of which are reverse-scored. However, because of the small number of items per sub-scale (i.e., 2) and questionable internal consistency estimates for some of those sub-scales (ranging from .55 to .81), it is not recommended that sub-scale scores are reported for this measure (Raes et al., 2011). The total score on this measure is calculated by averaging the mean of all sub-scales (Raes et al., 2011). This method of scoring the SCS-SF results in a maximum score of 5, and higher scores indicate higher levels of self-compassion. The validation study of this measure reported the internal consistency estimate was good (α = .87; Raes et al., 2011).

AIPF

The AIPF is an 8-item measure that was developed in the first phase of this study as a brief instrument for assessing the impact of ADHD on functioning in a range of psychosocial domains. This measure comprises two sub-scales with four items on each sub-scale. Items are scored on a Likert scale on which 0 = This is not at all true for me and 5 = This is very true for me. One sub-scale assesses the impact of ADHD on external domains and the other assesses the impact of ADHD on internal domains of psychosocial functioning. The scores on each sub-scale range from 0 to 20, and the score on the total scale ranges from 0 to 40; higher scores indicate higher impact of ADHD on psychosocial functioning. Estimates of internal consistency were adequate for both sub-scales and the total scale (external impact α =.74; internal impact α = .84; total scale α = .84).

Procedure

As with the first phase of this study, Phase 2 was initially advertised on a university research website and then broadcast on national radio programs and in print articles across a number of Australian media outlets. Potential participants were invited to complete an expression of interest, on completion of which they were provided with information about this study, and invited to contact the researchers for additional information prior to providing consent. After providing informed consent, participants completed the online questionnaires via Qualtrics. Participants were able to complete the questionnaires in multiple attempts, if required. All participants completed the measures in the same order, namely, a demographic questionnaire, the AIPF, SCS-SF, and MentS. This sequence ensured demographic data were collected first, followed by psychosocial impact assessment data and psychological construct data, thereby minimising response bias.

Phase 2: Results

Data screening was conducted to assess for missing values, significant outliers, and breaches of the assumptions of normality, specifically skewness and kurtosis. There were no missing data and no breaches of normality, so no transformations of data were required.

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics for each of the study variables are depicted in Table 4.

As presented in Table 4, all scales and sub-scales demonstrated good to excellent estimates of internal consistency, with the exception of the MentS-M, which has been found to exhibit lower internal consistency in clinical samples (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018). Given these previous findings, this sub-scale was retained for further analysis, acknowledging that this sub-optimal internal consistency estimate should be considered when interpreting results pertaining to that sub-scale.

Previous research has demonstrated that scores on the MentS vary by gender and among community and clinical samples (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018), so it was of interest to consider the scores on that measure in this sample for the purpose of comparison with previous clinical and community samples. Specifically, in the validation study of the MentS, Dimitrijevic et al. (2018) presented mean scores on each sub-scale for a number of samples across two studies, namely a normative sample (study 1), and a clinical sample (BPD) versus a control sample (study 2). In addition, mean scores on each sub-scale were presented based on the attachment styles of secure, fearful, dismissing, and preoccupied. In a further validation study of the MentS, Richter et al. (2021) provided these scores for a mixed clinical sample. These scores, together with the scores from the current study, are presented in Table 5.

As depicted in Table 5, variation in the pattern of responses was noted when comparing the samples to which the MentS was administered. Given the differential scoring of the various sub-scales (i.e., the MentS-S is scored out of 40 and the other two sub-scales are scored out of 50), the mean scores for each sub-scale were scaled so that all scores were out of 100. This scaling of scores facilitated comparison of scores across sub-scales and samples. However, the authors acknowledge that this transformation is illustrative only, and more meaningful comparisons would be achieved with statistical comparisons with the original data sets. Figure 1 presents the scaled scores for the sub-scales for each of the samples from Dimitrijevic et al. (2018), the clinical sample from Richter et al. (2021), and the current study.

As depicted in Figure 1, the sample from the current study scored higher on the MentS-M than did other samples, the closest sample on this sub-scale being the secure attachment sample. The score of the current study’s sample on the MentS-O was similar to that of the BPD sample, and the score of the current study’s sample on the MentS-S was similar to those of the fearful attachment sample and mixed clinical sample.

A within-subjects ANOVA was performed to compare the scaled scores on each of the sub-scales in the ADHD sample. That ANOVA was highly significant, F(2, 87) = 106.73, p < .001, demonstrating a large effect size η² = 0.71. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that the differences between each of the sub-scales were significant, as follows: MentS-S (M = 57.11; SD = 16.41) versus MentS-O (M = 78.85; SD = 11.95): Mean Difference = −21.75, p < .001; MentS-S (M = 57.11; SD = 16.41) versus MentS-M (M = 82.31; SD = 9.95): Mean Difference = −25.21, p < .001; and MentS-O (M = 78.85; SD = 11.95) versus MentS-M (M = 82.31; SD = 9.95): Mean Difference = −3.46, p = .002. These patterns of findings have interesting implications when considering the clinical presentation of ADHD and how this may compare with individuals with other psychiatric diagnoses and a range of attachment styles.

Inferential Statistics

Correlations were calculated among the study variables, and these are presented in Table 6.

The pattern of correlations presented in Table 6 indicates that, as hypothesised, MentS-S was significantly correlated with all study variables. However, the scores on MentS-O did not correlate with any other study variable, and MentS-M correlated with only the SCS-SF. In addition, scores on the total MentS were significantly correlated with SCS-SF and the AIPF-Ext but not the AIPF-Int or the total AIPF scores. Therefore, MentS-O, MentS-M and MentS were excluded from additional analyses. Given the consistency of relationships identified among the sub-scales and total scale scores on the AIPF, the total score on the AIPF was included in further analyses, while the sub-scales of that measure were omitted.

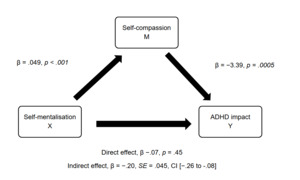

Regression and Mediation Analyses

To investigate the role of self-related mentalisation and self-compassion as predictors of ADHD impact, and to explore the possibility that self-compassion may be a mediator of the relationship between self-mentalisation and ADHD impact, a series of linear regression analyses was conducted, consistent with the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986). Simple linear regression analyses indicated that both self-mentalisation, R2 = 0.82, F(1, 87) = 7.73, p = .007, and self-compassion, R2 = .196, F(1, 87) = 21.20, p < .001, were significant predictors of ADHD impact. When these predictors were entered together into a multiple regression analysis, the overall regression was statistically significant, R2 = .20, F(2, 86) = 10.844, p < .001, and self-compassion remained a significant predictor (β = −3.4, p < .001); however, self-mentalisation was no longer a significant predictor of ADHD impact (β = −.07, p = .45), indicating a possible mediation effect. To test this possibility, a mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS macro model 4 with 5,000 bootstrap confidence intervals (Hayes, 2022). The mediation model included self-mentalisation as the predictor variable, self-compassion as the mediator, and ADHD impact as the outcome variable, as depicted in Figure 2.

The total effect of the model was found to be significant, β = −.24, SE = .09, CI [−.41 to −.07], p = .006. The direct effect was not significant β = −.07, SE = .09, CI [−.26 to −.11], p = .445; however, the indirect effect was significant because the bootstrap confidence interval did not contain 0, β = −.20, SE = .045, CI [−.26 to −.08]. The mediation index was β = −.2, SE = .05, CI [−.31 to −.103], which is indicative of a small to moderate effect size. These findings indicate that self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-mentalisation and ADHD impact.

Phase 2: Brief Discussion

In Phase 2 of this study, the relationships between mentalisation, self-compassion, and the psychosocial impact of ADHD in adult women were explored. Scores on the sub-scales of the Mentalisation Scale were compared across samples, and the differences in those scores in the current study’s sample were analysed. Significant differences were found between each of the sub-scales; scores on Self-Related Mentalisation were the lowest, and scores on Motivation to Mentalise the highest. As hypothesised, self-mentalisation and self-compassion were significant predictors of the psychosocial impact of ADHD. Specifically, low self-related mentalisation capacity predicted higher psychosocial impacts of ADHD, and higher levels of self-compassion predicted lower psychosocial impacts of ADHD. Of particular interest was the finding that self-compassion mediated the effect of self-mentalisation on ADHD.

Comparing the pattern of scores on the sub-scales of the Mentalisation Scale across clinical and normative samples (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2021) provided interesting insights into the respective sociocognitive profiles of those samples. Although those comparisons were not statistically analysed, some important observations were made. The scores on the Self-Related Mentalisation sub-scale of the mixed clinical, fearful attachment, and ADHD groups were highly similar to one another, and notably lower than scores for the other samples, suggesting a potential overlap in self-related mentalisation difficulties across diagnostic categories. Conversely, the scores on self-related mentalisation of the control and secure attachment groups were similar to one another, and notably higher than for the other samples. These patterns provide further support for the notion that self-related mentalisation is a crucial sociocognitive process associated with psychosocial outcomes. In particular, self-related mentalisation may serve as a protective factor against psychopathology (Bateman & Fonagy, 2019) and also represent a helpful index of outcome severity in clinical groups (Perroud et al., 2017). Although not specifically investigated in this study, the similarities between the fearful attachment group and the ADHD group are consistent with emerging literature recognising the interplay between ADHD and trauma-related symptomology (Craddock, 2024; Witteveen & O’Hara, 2025), which warrants further investigation.

Another pertinent finding related to the pattern of scores on the Mentalisation Scale sub-scales was the significant differences between each of the sub-scales in this ADHD sample. The largest difference was found between the high score on Motivation to Mentalise and the low score on Self-Related Mentalisation. The discrepancy between these two sub-scales is reminiscent of themes that emerged in a recent qualitative study—in particular, the observation that many aspects of ADHD can be understood as cognitively and emotionally paradoxical (Witteveen & O’Hara, 2025). In the context of this study’s findings, the paradox can be recognised as individuals wanting to be able to understand their own behaviours and motivations (high scores on Motivation to Mentalise) while simultaneously recognising challenges in this regard (low scores on Self-Related Mentalisation). Although the theme of paradox was not a specific focus of the current study, the alignment of these scores on the Mentalisation Scale with those qualitative findings is noteworthy and further emphasises the complex sociocognitive challenges experienced by individuals with ADHD.

These findings are also consistent with those of previous studies that have identified mentalisation as a potential mechanism underpinning some of the emotional dysregulation and sociocognitive challenges associated with a range of diagnoses, including BPD (Bateman & Fonagy, 2009) and ADHD (Badoud et al., 2018; Perroud et al., 2017). In addition, these findings align with research that has identified that self-mentalisation—as a substrate of mentalisation—may be uniquely implicated in negative psychosocial outcomes in clinical samples (Dimitrijevic et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2021), thereby extending the findings of previous studies to women diagnosed with ADHD. Also consistent with previous research, the role of self-compassion as a protective factor against negative mental health outcomes in general (Inwood & Ferrari, 2018) and in ADHD specifically (Beaton et al., 2020, 2022) was further emphasised in the current study, and the clinical relevance of both these constructs that were previously identified in adolescents with ADHD (M. Huang & Hou, 2023) was extended to this sample of women with ADHD. The limitations of this phase of the study and implications of these findings, together with recommendation for future research, are discussed in the General Discussion following.

General Discussion

Summary of Findings

This study comprised two phases. In Phase 1, a brief measure of the impact of ADHD on psychosocial functioning was developed and a preliminary assessment of its factor structure and reliability indices was conducted. Initial indicators supported its overall structure and suitability for use, and that measure was employed in Phase 2, which investigated the influence of mentalisation and self-compassion on the psychosocial impact of ADHD in adult women. As hypothesised, low self-mentalisation was associated with high psychosocial impact of ADHD, and this association was fully mediated by self-compassion. These findings align with previous research (Badoud et al., 2018; Beaton et al., 2022; M. Huang & Hou, 2023) and extend identification of the influence of self-mentalisation and self-compassion on the psychosocial impact of ADHD to adult women.

Implications and Recommendations for Further Research

In addition to the development and preliminary validation of a brief measure of psychosocial functioning in adults with ADHD, this study identified a number of interesting findings pertaining to the sociocognitive profile of a sample of women with ADHD. These findings have implications for enhancing understanding of the mechanisms of difficulty associated with attentional control and emotion regulation in women with ADHD, as well as informing the development of targeted therapeutic approaches for this population.

Comparing scores on the Mentalisation Scale with other normative and clinical samples indicated that self-mentalisation may be particularly difficult for fearfully attached and mixed clinical samples, as well as for women with ADHD. These findings have two specific implications for further research. First, in recognition that fearful attachment and significant clinical diagnoses are commonly associated with trauma (Zagaria et al., 2024), additional research investigating the relationship between trauma and ADHD is recommended.

Second, the notable challenges associated with self-mentalisation identified in this sample highlight the potential utility of targeting this construct in therapy as a way to enhance therapeutic outcomes. Previous research has supported the utility of mentalisation-based treatment for adults with BPD (Bateman & Fonagy, 2009) and other personality disorders (Volkert et al., 2019), while preliminary support has been found for the effectiveness of this approach for adults with ADHD (Badoud et al., 2018). The current study’s findings further support this approach and suggest that using therapeutic modalities that focus on the enhancement of self-related mentalisation processes may enhance therapeutic outcomes for women with ADHD. Further, the finding that self-compassion fully mediated the relationship between self-mentalisation and psychosocial outcomes associated with ADHD is consistent with previous recommendations that therapeutic emphasis on augmenting self-compassion with clients who have a diagnosis of ADHD is worthy of further investigation (Beaton et al., 2022; M. Huang & Hou, 2023).

Limitations

Despite the robust findings of this study, a number of limitations are noted. Participants self-selected via media recruitment, so it is possible that those who participated were highly motivated to understand their ADHD and mental health. This may have resulted in an overrepresentation of individuals with high introspection, possibly affecting average mentalisation scores. Also, the educational attainment level of this sample was notably higher than in samples of other studies investigating women with ADHD, so it is unclear to what extent (if any) educational attainment may have influenced these findings. Ethnicity and socioeconomic characteristics were not collected in this study. Future studies should ensure diverse sampling of socioeconomic, ethnicity, and educational attainment to assess generalisability.

All data were collected via self-report measures, which may introduce response biases such as social desirability or self-perception errors. The cross-sectional design of this study prevents conclusions about causal relationships between mentalisation, self-compassion, and ADHD impact. Longitudinal studies tracking these variables over time would clarify developmental trajectories and the relationships between these variables. Additional research that directly investigates the sociocognitive profiles of a range of clinical and comparison samples is recommended to clarify further the role of mentalisation generally, and self-mentalisation specifically, along with self-compassion, in influencing psychological disorders and associated psychosocial outcomes.

With regard to the validation of the AIPF, it is recognised that additional evaluation of that measure, with particular reference to construct validity and test-retest reliability, is required. In Phase 2, the rescaling of the sub-scale scores facilitated observational comparisons only, and no statistical analyses were conducted in relation to these observations. Therefore, any conclusions drawn from those comparisons must be considered tentative, requiring further investigation. While the insights derived from these comparisons were of interest, formal statistical comparisons with the original datasets would strengthen and refine ADHD-specific interpretations.

Conclusion

This study contributed to enhancing understanding of the importance of self-mentalisation and self-compassion in the psychosocial outcomes of women with ADHD and identified several areas worthy of further investigation. Preliminary comparisons indicate some similarities between self-mentalisation patterns in women with ADHD and other clinical groups, including populations known to have experienced trauma. However, because trauma was not directly assessed in this study, further investigation is required to determine whether these patterns reflect underlying trauma-related mechanisms or are distinct features of ADHD’s sociocognitive profile. In addition, the relationships between self-mentalisation, self-compassion, and the psychosocial impact of ADHD indicate the potential utility of exploring therapeutic approaches that emphasise augmenting self-mentalisation and self-compassion capacities in women with ADHD. Taken together, these findings provide further clarity in relation to the sociocognitive profile of women with ADHD and identify plausible therapeutic approaches, consistent with the aim of enhancing therapeutic outcomes for this group.