Hope-Focused Therapy: A Framework Outline

It is well established that the many theories and approaches to psychotherapy and counselling are more or less effective based on the adherent therapist’s ability to activate the common and specific factors required for necessary change (Zilcha-Mano et al., 2019). While therapists may be following theory-specific protocols, it is the intersection between these protocols, therapist and client factors, and common factors that enable change. As well described by Jerome Frank (1963), the benefit of a theoretical approach is that it provides the therapist with a rationale for what to do—a schematic or map of how to traverse the terrain of therapy. While the common and specific factors are essential, therapists need a way to apply them.

One of the reasons that so many different theories of psychotherapy and counselling exist is that people hold different views about which change mechanisms to use and how and when to apply them. The human condition is dynamic, and so it is unsurprising that people appreciate and engage with this dynamism differently. However, all therapeutic approaches are founded on distinct foundational ideas. Hence, psychodynamic theories focus on intrapsychic structures, humanistic theories on self-actualisation and agentic meaning-making, cognitive behavioural approaches on cognition and behavioural activation, and post-structural approaches on narratives and social power dynamics. Moreover, change is best effected when the therapist is responsive to the specific needs of the client moment by moment (Fimiani et al., 2022). Effective therapy occurs when the therapist integrates theory and process in the most salient moments of therapy.

An approach for remaining focused on client needs, that is, remaining responsive, is to keep the client’s hope central within the therapeutic process (Hatcher, 2021; Larsen et al., 2007; D. O’Hara, 2013). As Frank (1963) explained, people come to therapy because they have been demoralised, having lost some measure of hope in their lives. Hope-focused therapy is founded on the view that hope is a primary driver of human development throughout the lifespan and acts as a barometer of psychological wellbeing (Erikson, 1961; Trzebiński & Zięba, 2004). This being the case, hope provides a valuable responsiveness heuristic. Paying attention to a client’s sense of demoralisation or hopefulness within the minute moments of therapy increases the accuracy of responsiveness. While such acuity can be learned, it is supported by consulting a guiding map of the therapeutic terrain. The following section describes the theoretical influences underpinning hope-focused therapy and indicates how the approach frames therapy.

Theoretical Foundations

Trust and Hope as Foundations of Wellbeing

Commentators across a variety of disciplines have noted the relationship between trust and hope. In psychology, the first to recognise this link were Ernst Bloch (1954–1959/1986) and Erik Erikson (1961). Both understood that hope involves a form of trust in the potential for positive change and the belief that individual and collective efforts can lead to better futures. Erikson believed that for hope to emerge, individuals should have experienced relationships of trust that provided a foundation for seeing or believing in the possibility of a positive future. He viewed hope as a developmental process arising from experiences of trusting relationships. Erikson stated that “the rudiments of hope rely on the new being’s first encounter with trustworthy maternal persons who respond to his reach for intake and contact with appropriate provision” (p. 153), and “the gradual widening of the infant’s horizons of active experience provides, at each step, verifications which inspire new hopefulness” (p. 154).

Expressing similar sentiments, Trzebiński and Zięba (2004) asserted that relational trust establishes a foundational worldview, which they called basic hope. Basic hope is founded on two views of the world: (a) its order and meaning and (b) its positiveness. They stated, “The role of basic hope is to stimulate and to support an individual’s constructive way of dealing with important loss or with challenges and new opportunities in an individual’s life” (p. 174).

From an attachment theory perspective, this trust–hope connection is an essential feature of building an internal working model of secure attachment (Munoz et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2022). Studies have demonstrated that hope and trust are positively correlated with secure internal working models of the self (Kintanar & Bernardo, 2013; Simmons et al., 2009). If this is true, then an insecure internal working model would reflect disruption in the developmental process between trust and hope. Thankfully, it is known that while early internal working models persist into adulthood, they can be adjusted and updated (La Guardia et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2021). This being the case, basic hope can also be recalibrated, leading to a different worldview and mental health status.

If it is possible that early attachment schemas or internal working models can be positively adjusted, then how can psychotherapy and counselling actively encourage this adjustment? According to Fonagy and Allison (2014), the mentalisation process is the primary process in attachment and therefore is also the primary mechanism through which any schemas are adjusted. Mentalisation is “the capacity to evoke and reflect on one’s own experience to make inferences about behavior in oneself and others” (Levy et al., 2006, p. 1029). Essential to the development of mentalisation is the mirroring process. This occurs when parents and caregivers help infants and young children to identify and reflect on their different emotional states, organically providing a link between experiencing and meaning. Notably, human brains have the capacity to attend to non-verbal cues, especially facial cues, and in so doing elicit similar neural activity in the observers and the observed (Carr et al., 2003). Mentalisation extends the mirroring process by providing a conscious reflective dimension to the natural mirroring feedback received from others. The more parents intentionally mentalise their child’s cognitive and affective states, the more the child becomes aware of their own internal experiences, which builds the child’s relational trust and thus increases their chance of developing secure attachment (Ringel, 2012).

Just as secure attachment increases an individual’s acquisition of mentalising capacity, it is also essential in the development of epistemic trust. As Fonagy and Allison (2014) explained, epistemic trust is “an individual’s willingness to consider new knowledge from another person as trustworthy, generalizable, and relevant to the self” (p. 373). A child who feels secure can relax epistemic vigilance and receive and accept new knowledge from a trusted other. Epistemic trust is facilitated not only via a relationally secure environment but additionally by somatic cues communicated by the other. Human beings are “hard wired” neurologically to perceive and respond to such cues as eye gaze, facial expression, voice prosody, and body posture. When these cues reflect an open, interesting, and non-threatening set of somatic markers, the receiver is more likely to pay attention to the communication and also to accept the information, or at least weigh it up in an open-minded manner. Secure attachment and epistemic trust are both developmental requisites for the establishment of basic hope and form a reciprocal relationship—openness to experience and readiness to explore are complementary.

Identity and Wellbeing

Much research on the topic of personal identity has been conducted, garnering a wealth of knowledge about how human beings understand themselves. William James (1890) described the self as a stream of consciousness comprising two poles, one of phenomenological experiencing and the other of reflection upon experience. The ability to pause and reflect provides insight in the cognitive frame of self-concept and the experiential frame of sense of self. Erikson (1950) argued that identity is developed progressively and dynamically over the lifespan, facilitated by age-related crises. As people confront these crises, they grapple with their sense of self and their relationships, values, and life purpose. Identity is a complex topic and includes other related areas of research, such as social identity (Stets & Burke, 2000), self-efficacy (Bandura, 1995), and multiple identities (Gergen, 2009).

One framework for understanding identity that has received much attention in recent years is self-determination theory. Deci and Ryan (2000) examined the place of motivation in human development, highlighting the significance of intrinsic motivation in personal development and wellbeing. Similarly to Erikson (1950), they asserted that there are three basic human needs that are inherent drivers of psychosocial development: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy reflects the need to be congruent with one’s intrinsic motivation, personal values, goals, and actions. Competence is driven by the desire to gain mastery, to explore and extend oneself. Relatedness is the need to connect with others and to be encouraged and affirmed; relatedness also involves the offering of oneself in support of others. As La Guardia (2009) stated, “In sum, the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness underlie natural inclinations towards engaging in interesting and self-valued activities, exercising capacities and skills, and the pursuit of connectedness with others” (p. 92).

Central to the theoretical framework of hope-focused therapy is the view that hope itself is a central driver of human development. This is consistent with the views of Erikson (1950) and others (Bryce & Fraser, 2023; Trzebiński & Zięba, 2004) that the early development of hope provides the foundation upon which the satisfaction of needs, such as those proposed by Deci and Ryan (2000), rest. Without a foundation of hope, the motivation for developing agency, competence, and relationships is, to varying degrees, thwarted. Given this perspective, hope is understood to be a central factor within therapeutic change. The place of hope may vary depending on the presenting problem and the stage of therapy, but its relevance to wellbeing remains central. In the early stages of therapy, the client’s experience of hope is often quite limited. In later stages, hope is progressively recovered, enlivening the movement towards wellbeing. Hope then can be viewed as an undergirding foundation for the development of self and a sense of personal identity.

Without basic hope, the self lacks trust in a world of possibilities and one’s place in it. In a study in which therapists were asked about the place of hope in psychotherapy, participants responded that client and therapist hope had two primary sources: internal and external (D. J. O’Hara & O’Hara, 2012). The internal form of hope was based on self-validation or confidence in one’s capacities and capabilities. The external form of hope had several sources: interpersonal support, societal support and cultural lore, and spirituality. These distinct sources of hope can be drawn on at different times throughout the lifespan and in various combinations. For example, cultural lore, which involves implicit cultural beliefs and practices such as ceremonies and celebrations, may be a central source of sustenance in certain periods of life and less so in others. Similarly, belief in one’s own capacities may bolster one’s identity and hopeful outlook in developmentally relevant periods but become less a source of hope at other times, necessitating reliance on other sources of hope such as interpersonal support and spirituality. The therapist’s task, in part, is to aid clients in accessing sources of hope that are relevant and meaningful for them in the present moment.

A central aspect of identity is life purpose, since purpose provides personal meaning and coherence (Swann & Buhrmester, 2012). One of the ways people express purpose is through the goals they choose. Carver and Scheier (1998) proposed that human behaviour is largely organised around goals and that goals are ordered hierarchically. The more abstract higher order goals organise the concrete lower order goals. The higher order goals reflect an individual’s identity and values and provide motivation for behaviour; thus, they are related to wellbeing. This view is supported by the self-concordance model, which finds strong evidence that pursuing goals that reflect intrinsic interests and values leads to greater persistence and wellbeing (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; Sheldon & Goffredi, 2023). Given the association between identity, goals, and wellbeing, it is reasonable to think that identifying and working with goals in therapy will naturally reflect a client’s personal identity and values, giving direction to the therapeutic process (Cooper & Law, 2018).

The Play Space

People come to therapy with varying degrees of clarity and awareness about their goals and intentions. Sometimes, the most people are aware of is that they feel demoralised about some aspect of their life and want to discuss what is happening. At other times, awareness has crystalised into clear goals for therapy. Whether the goals for therapy are clear early or emerge over time, once a focus has been determined, the next step is to decide how to work with the problem. Here, I have called “working with the problem”, “play”. Initially, play might seem an odd term to use for the work of therapy, but play, rightly understood, is an excellent metaphor for the work of therapeutic change.

Play has many qualities. It involves exploration, imagination, reverie, and fun. To explore, one needs to feel safe so that the imagination is free to roam among alternative realities. As play researchers Vadeboncoeur and Göncü (2018) expressed, “Imaginative play emerges, in part, as individuals attempt to make sense of their lived experiences, to interpret actions and events, and to predict and create their futures” (p. 258).

This is what children are doing when they play. Both Vygotsky (1967) and Piaget (1929) believed play to be essential for cognitive development, for in play children create imaginative situations that help them to navigate and make sense of their world. In a similar way, Donald Winnicott (1971) understood play as a transitional space in which the child integrates their inner and outer realities. The integration process afforded by play is more than a cognitive exercise; it fundamentally involves the whole person and especially one’s emotions. Winnicott stated, “It is in playing and only in playing that the individual child or adult is able to be creative and to use the whole personality, and it is only in being creative that the individual discovers the self” (p. 73).

Consciousness researchers would describe the process of play, at least in part, as involving anoetic consciousness (non-conscious form of awareness). By this is meant that a state of play not only provides individuals with opportunities to create conscious associations between narratives and symbols (e.g., toys and drawings) but also, in moments of unreflective reverie, supports non-conscious feelings and body states to emerge into nascent awareness, potentially integrating feeling memories with cognitive consciousness (Panksepp, 2009; Vandekerckhove & Panksepp, 2009). This process entails more than cognitive reflection because nascent awareness emerges from pre-reflective memories—a combination of unrecognised feelings and body sensations. The seminal action here is that when provided with an environment of safety and the space to enter reverie, opportunity is made for these non-conscious or unreflected states to bubble towards the surface into tentative recognition, allowing for a degree of connection with reflective awareness (Alcaro & Carta, 2019). To put this another way, when unreflected feelings and somatic states can be attended to, the possibility arises of an integration with cognitive awareness. This might be regarded as a deep form of self-mentalisation.

The challenge for the psychotherapist or counsellor is to provide, where possible, the opportunity for this level of integration to occur. While therapists know that effective therapy will involve the presence of a well-developed therapeutic relationship, this may not be sufficient for genuine play to emerge. Therapists and clients may have an effective therapeutic relationship but principally work at a cognitive level of processing. While therapy of this kind has much merit, it is not likely to provide an environment for play. Of course, play in psychotherapy cannot be forced, but when therapists are attentive to the minute particulars of the therapeutic moment, are aware of somatic and feeling states, and do not disturb the instances of anoetic upwelling, an integration of previously non-conscious and conscious awareness becomes possible (Alcaro & Carta, 2019; Bierschenk, 2021).

Therapeutic Action

The term action has many connotations in the context of psychotherapy and counselling. Typically, action refers to some form of intervention by the therapist or an act performed by the client to facilitate and support the change process. In a broad sense, all of therapy is an action. The acts of active listening, of developing a case formulation, and of applying a particular strategy all constitute actions. A narrower use of the term refers to a category of action. A useful way of conceptualising categories of action is to focus on what the client’s need is at a particular moment or stage and thus what related therapeutic tasks are required to meet the need.

In hope-focused therapy, four high level actions or tasks are identified:

-

working with blockages to therapeutic change and wellbeing

-

identifying pathways towards goals

-

engaging in psychoeducation

-

working with acceptance.

Working With Blockages

In the first category—working with blockages—five areas may need to be addressed:

-

intrapsychic and interpersonal conflict

-

personal deficits

-

enactments, that is, intractable problematic patterns of relating

-

withdrawing—struggling to stay personally engaged

-

meaning reconsolidation (Stark, 1999).

Intrapsychic and Interpersonal Conflict

A common blockage to wellbeing arises from the inner world. When people are confused about their identity, perceptions of others, and life in general, they are internally conflicted. Sometimes they feel the effects of this inner conflict but do not know the reason, since it remains largely unconscious. At other times individuals have a level of awareness of the tension, often evidenced in maladaptive cognitions on which they ruminate. Whether the focus of inner conflicts is primarily about people’s self-conceptions or conceptions of others, their unprocessed inner conflicts need to be addressed (Stark, 1999).

Since hope-focused therapy is an integrative model of practice, it allows for a breadth of therapeutic interventions drawn from across the theoretical spectrum to address these inner conflicts. For example, for internal struggles that are less defined, psychodynamic interventions may be appropriate. When inner cognitions are more conscious, cognitive behaviour therapy may be the approach employed. The central issue is recognising that hope will be stalled or thwarted if inner conflicts are not addressed.

Personal Deficits

Sometimes people’s struggles are influenced by a developmental lack. No one has had a perfect upbringing, but as Winnicott (1965) stated, as long as people have had a “good enough mother”, that is, sufficiently supportive parenting and caregiving experiences, they generally have the necessary inner resources to thrive. However, many people have not received adequate nurturing and have arrived in adulthood still seeking affirmation, love, and recognition. While these needs exist throughout life, when an individual experiences a significant dearth of them, the drive to meet these needs can be overwhelming, distorting perceptions of self and other and leading to maladaptive strategies to satisfy them.

A poignant example of an outcome of developmental deficit is narcissism. When an individual does not receive appropriate love, recognition, and affirmation in their developmentally formative years, this can lead to a maladaptive approach to need satisfaction, usually in the form of narcissistic manipulation and control. At the very least, such an individual will view and relate to others less for who they are and more as objects of need satisfaction. In the words of Martha Stark (1999, p. 253), they will pursue a “relentless hope” that the primary other will be and do what they expect in the hope that their deficits will be met. Heinz Kohut (1971), acknowledging this fact, believed that the focus of therapy for such individuals should be the provision, over time, of the affirmation and care that was not present when it should have been. While therapeutic nurture will provide some measure of healing, the process will also require a recognition by the individual that the appropriate developmental timeline for provision has passed, and therefore its loss will also need to be acknowledged and grieved. Once a degree of provision has been provided and the grieving process completed, hope will return.

Enactments

Enactments refer to the acting out of inner conflicts and deficits in inappropriate ways. A good example of enactment is the transference process. This occurs when individuals project (transfer) unprocessed relational issues onto others; for instance, a person raised in a highly rigid and authoritarian family system who resented the demands and expectations placed on them now projects their angst and resentment onto non-family members.

The key to resolution of enactments is the opportunity to work through inner struggles with a safe person. It is not usually sufficient in such cases for this to be completed alone. Because problems arise in relationships, they typically are resolved through relationships. Stephen Mitchell (1988), famous for promoting the relational turn in psychotherapy, asserted, “There is no ‘self’ in a psychologically meaningful sense, in isolation, outside a matrix of relations with others” (p. 33). It is through healthy relationships that we are healed.

Withdrawing

Sometimes, when an individual has struggled to resolve personal issues and has exerted energy over a long period to find a way forward without success, they become disillusioned and give up the struggle. The result can be a withdrawal from life. This is not in the form of suicidal ideation but a withdrawing of life energy, a loss of investment in seeking to thrive (Stark, 1999). Such people still hold down jobs and are broadly amenable to relationships, but they live functional lives of quiet desperation. Unlike those stuck in enactments who remain in the struggle to resolve life issues, those who have withdrawn have given up the struggle. In therapy, such people relate well cognitively but hold back emotionally because investment in feeling is too much. The task of therapy in these cases is to draw them back into life, to woo them to risk genuine relating. The challenge for the client is to re-engage in life to find hope that life may still have its rewards. The therapist’s task is thus to hold hope for the client, while helping them find hope themselves, or even helping them by co-creating hope (Larsen et al., 2007).

Meaning Reconsolidation

One of the principal tasks of therapy is to find new meanings for life’s circumstances. Often, new meaning arises simply through discussing problems with a therapist, exploring the aetiology of problems and finding solutions. In some situations, adequate understanding and insight remains elusive. This may be for many reasons, including the client’s level of readiness, the degree of difficulty of the problem, or stimulus (neurological) entrapment. Since cognition is never without emotional valence, traumatic memories can be reignited in “as if” conditions, wherein people are reminded of past traumas whether consciously or non-consciously. This is a form of stimulus entrapment. In such conditions, our neurological system is subverting individuals’ attempts to understand. In these situations, the process of meaning-making requires memory reconsolidation, whereby the valence of past trauma memories is reduced through dual awareness strategies, allowing for more accurate and facilitative meaning to emerge (Ecker & Vaz, 2022). Here, therapy offers a new hope by reordering memories through neurological reprocessing (Ecker & Bridges, 2020; Mehuron, 2019).

Identifying Pathways Towards Goals

A seminal researcher on hope is Rick Snyder. Snyder (2000) believed that hope was best understood as a combination of three elements: goals, pathways or routes towards goals, and agency or motivation to pursue goals. Research has found that high hope people, unlike low hope people, are not only good at identifying a range of pathways towards goals but also cognitively flexible in adjusting to new routes when others are blocked. Low hope people identify a more limited range of routes and are less flexible when routes are blocked. On occasion, the primary action or task of therapy is to help clients identify goals and pathways and support them to maintain the motivation to pursue them.

Engaging in Psychoeducation

Sometimes the task of therapy is to inform. While there is always a danger that the therapist might presume they have sufficient knowledge or know what knowledge the client may lack, equally the right piece of information can make all the difference in resolving a problem (Ditlefsen et al., 2021). Knowledge, appropriately timed and delivered, can restore a client’s hope in their circumstances. As an example, a study on the potential link between psychoeducation and hope in the context of trauma experiences found that psychoeducation significantly increased the participants’ hope measures and wellbeing (Çakmak et al., 2025). Sometimes knowledge is the key to change.

Working With Acceptance

Life is complicated. There are times when people do everything possible to change a situation and yet nothing happens; the status quo remains. These can be very challenging times, often confusing, resulting in people questioning their worldview. When one’s current understanding of life is in question, it can feel like one’s foundations are crumbling. This usually signals a time of deep reassessment and transition.

If all other avenues of understanding and processing the situation have been exhausted, only two reasonable options may remain: one, that an individual accepts the fact that the situation cannot change, or two, that the individual changes. In either case, acceptance is the key (D. O’Hara, 2013; D. J. O’Hara, 2014; Petrocchi et al., 2025). Human beings usually struggle with acceptance, for at first sight acceptance feels like defeat. People prefer proactive solutions. They also often prefer not to change but rather for circumstances to change. When acceptance is the central need, the therapist’s task is to gently point the way. This requires a subtle and compassionate stance by the therapist. It will take time. At a deep level of human encounter, acceptance will be the pathway towards hope.

Applying Hope-Focused Therapy

Hope-focused therapy is an integrative approach founded on an organismic view of human functioning. It is holistic in terms of holding a biopsychosocial–spiritual view of humanness. As an integrative approach, it welcomes ideas and strategies from other theories of psychotherapy whenever these ideas and strategies seem best suited to meet the needs of clients in the moment. However, the approach acknowledges its interpersonal psychodynamic and humanistic foundations alongside the influence of neurobiological principles. It also understands that hope is central in healing and recovery and that hope acts as a barometer for the therapeutic process. In practice, the therapist pays close attention to somatic and feeling states, knowing that shifts in states reflect inner movements and awarenesses. The aim of therapy is a progressive integration of the whole person.

Practice Framework

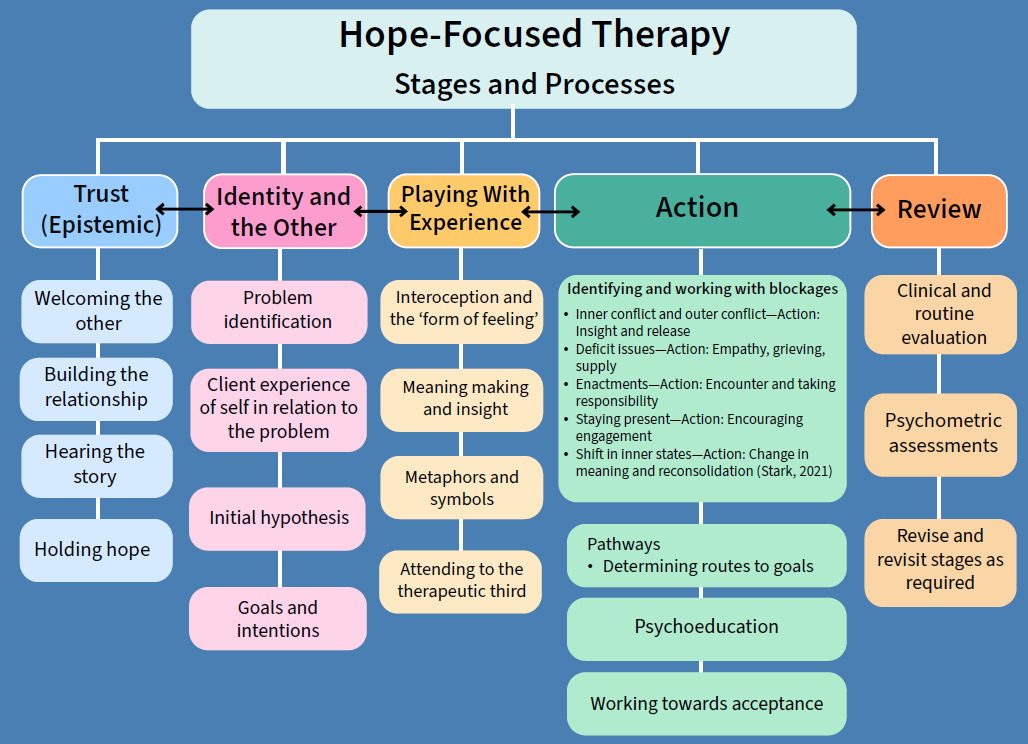

Psychotherapy is a meandering and iterative process but does progress through recognisable movements or phases. Figure 1 provides a guide to key points of focus through the different phases of therapy within hope-focused therapy.

Trust

As outlined earlier in the Theoretical Foundations, trust and hope are directly related and form the foundations of the therapeutic relationship. Knowing who to trust is a central dimension of building a relationship. This epistemic aspect of trust is established through facial and somatic cues. A therapist who appreciates the subtleties of communication provides verbal and non-verbal messages that signal to the client that they are a trustworthy person (Fonagy & Allison, 2014). This frees the client to tell their story and enables the therapy journey to begin. Since clients usually come to therapy with some degree of struggle or demoralisation, one of the early tasks of the therapist is to provide a holding space for the client’s hope for change.

Identity and the Other

One of the central tenets of hope-focused therapy is that human problems are fundamentally problems of the self. This is not to say that the aetiology of problems excludes societal influences; far from it. Human beings are relational by nature and therefore profoundly influence each other at all levels of interaction, whether that be in dyads, families, groups or whole societies. However, it is the individual’s response to these relationships that is the primary focus of psychotherapy and counselling. An individual’s response to relationships, at whatever level of interaction, is best reflected in their sense of identity and more precisely in their sense of self (Basten & Touyz, 2020). When people attend therapy, they are usually struggling with a sense of who they in relation to something. When awareness of this relationship between self and the “other” clarifies, it crystalises the focus for therapy. As the therapist listens to the problem story and explores with the client their sense of self in relation to the problem, the therapist can develop a tentative hypothesis or formulation of what gave rise to and what perpetuates the problem experience. The resulting focus is usually expressed in terms of an intention for change or a goal for therapy.

Playing With Experience

In a certain sense, all of the therapeutic process is a form of playing with experience. However, at this phase of therapy play comes into particular focus. One of the best ways of attending to experience in the moment is what Robert Hobson (1985) referred to as forms of feeling. The therapist attends to the client’s forms of feeling by paying close attention to somatic and feeling states. Hobson noted that the feeling state of a client tends to change in response to the therapist’s quality of responsiveness. When the therapist misses the mark, this influences the client’s state. A therapist who tracks with the client well provides the opportunity for client discovery, increased awareness, and inner connection (Stern, 2010).

The client’s inner world is only partially known by them since a good portion of life is non-conscious. As explained earlier in the discussion of play, much of human memory is anoetic and only connects with conscious awareness in what might be experienced as nuomenal moments. While therapy cannot produce such moments of awareness, it can provide the opportunity for their appearance. One of the most facilitative ways of allowing for such a possibility is through attending to symbols and metaphors. When a therapist listens intently to a client’s feeling and somatic states and their use of symbols and metaphors, surprising connections and insights are presented (Faranda, 2016; D. J. O’Hara & O’Hara, 2020). In terms of the process of therapy, this might be regarded as a movement from existing cognitive awareness towards the possibility of anoetic nuomenal (non-abstract, transcendental) upwellings, thereby leading to a new level of reflective awareness, as represented in Figure 2.

Because there is no “self” without an “other”, a deeper discovery of self is facilitated through relationship. At least three entities are present in therapy: the client, the therapist, and the relationship between them. This therapeutic third is a central aspect of the play space (Meares, 2020). Within it exists an ebb and flow of energy, a subtle communication of being. Each member of the dyad affects the space. An attentive and responsive therapist gains awareness from the movements within this space. New meaning arises not just via cognitive pathways but from the collective whole of the inner worlds of the client and therapist. This deepening inner connection is facilitated by the therapist attending to somatic and feeling states, noticing and amplifying these states so that the client becomes more aware of them, representing them in the form of symbols and metaphors (Meares, 2005). This process is illustrated in Figure 3.

Therapeutic Action

As outlined above, a range of actions may form part of the work of therapy. While all of the therapeutic process is a form of action, often the first targeted action or strategic intervention is to remove blockages to change. Sometimes, this is the central task of a whole course of therapy. When “stuckness” is freed, life flows. At other times or at a different phase of therapy, the action is to discern pathways towards achieving established goals. The therapist’s support of client agency and help in the identification of the means to reach personal life goals is a worthy therapeutic endeavour. This action is closely linked to the sharing of new ideas, a form of psychoeducation. In a certain sense, the process of psychotherapy and counselling is a learning process. In therapy, clients learn about themselves, others, and the world. It could be said that therapy is a form of deep personal learning. As Polanyi and Prosch (1975) famously noted, “all learning is personal learning” (p. 133).

Sometimes, the principal task is to bear witness to the client’s struggle and suffering. Not all problems have solutions. This is not to say that there is no healing response to the unsolvable. Rather, when all efforts to resolve the presenting problem have failed, it may now be that acceptance of the situation or personal change is required. One of the most powerful actions of a therapist is to witness; to appreciate at a deep empathic level the client’s pain and struggle. This is, itself, a healing act.

Review

The final phase of therapy is to review progress and, where appropriate, terminate therapy having achieved what was necessary. Endings are important because they celebrate and consolidate progress made and help clients affirm the foundations of their hope, thus reinforcing their capacity to navigate future challenges with greater self-awareness, confidence, and connection.

Review can involve several aspects including a therapist’s clinical review of progress or use of psychometric tools to measure certain client characteristics, such as depression, anxiety, and stress. Another well-established aspect of review is client routine evaluation (Duncan et al., 2003; Evans et al., 2002). Routine evaluation provides measures of broader indicators of progress, such as the quality of the therapeutic relationship and the client’s sense of progress, functioning, and wellbeing. Routine evaluation may provide information to both the client and the therapist throughout therapy as well as confirm that therapy has reached its goal.

Psychotherapy is not a linear process; rather, it is an iterative movement forwards and backwards in a progressive meandering towards change. The identified goals for therapy established earlier in the process may change as increased awareness informs more salient goals. This ebb and flow of thoughts and experiences reflects the fluctuations of hope. It is the task of the therapist to attend to the presence of hope, to hold hope when the client cannot, to challenge false hope when it confuses, and to nurture hope until the client holds it for themselves.

In conclusion, hope is well recognised as one of the common factors of change, but how it informs the process of change, and therefore the practice of psychotherapy and counselling, has been less clear. In this article, hope has been identified as a central driver in human development throughout the lifespan, and a framework for conceptualising an integrative, hope-focused process of therapy has been described. The framework draws on a breadth of existing theory and research using hope as a key integrating device. It is anticipated that by keeping in mind the iterative phases of Trust, Identity, Play, Action, and Review (TIPAR), novice and experienced therapists alike will be supported to maintain hope as a central focus within therapy.