Interoception—the process of detecting, interpreting, and integrating internal bodily signals—has gained increasing attention in recent decades for its role in human behaviour, emotional processing, and self-regulation (Farb & Segal, 2024; Leech et al., 2024; Lima-Araujo et al., 2022; Machorrinho et al., 2023; Price et al., 2023). Interoceptive signals include sensations such as hunger, thirst, breath, heart rate, and temperature, and also involve the conscious recognition of these signals and what they signify about emotional or physical states. Interoception supports homeostasis and adaptive responses to both internal and external stressors (Khalsa et al., 2018; Leech et al., 2024; Machorrinho et al., 2023).

Two key dimensions of interoception are widely recognised: interoceptive awareness (IAw) and interoceptive accuracy (IAc; Garfinkel et al., 2015; Vig et al., 2022). IAw refers to a person’s conscious awareness of internal sensations and the associated emotional meanings, typically measured through self-report. IAc, by contrast, reflects the objective ability to detect internal cues, such as heartbeats or breath rate, and is measured using physiological tasks.

In addition to these behavioural and self-report measures, neuroimaging methods—particularly functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)—have provided insights into the neural substrates of interoception. Neuroimaging studies show that the insula plays a central role, with the anterior insula linked to emotional regulation and the posterior insula responsive to pain, cardiac signals, and visceral sensations (Harricharan et al., 2017). Other involved brain regions include the bilateral amygdala, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, and parahippocampus (Nicholson et al., 2016; Scalabrini et al., 2024).

Disruptions to interoception—whether under-sensitivity (hypo) or over-sensitivity (hyper)—can impair emotional self-awareness and regulation, both of which are essential to counselling and therapeutic practice (Farb & Segal, 2024; Leech et al., 2024; Ogden et al., 2006; Price & Hooven, 2018). Hypo-sensitivity may reduce a person’s ability to detect internal cues of distress or arousal, making it harder to regulate or even recognise emotion (Reinhardt et al., 2020; van der Kolk, 2014). Hyper-sensitivity, conversely, can lead to overwhelm and difficulty calming down. Both forms of interoceptive dysfunction contribute to poor mental health outcomes and are often seen in clients experiencing stress, trauma, or emotional dysregulation (Farb & Segal, 2024; Ogden et al., 2006; Price & Hooven, 2018).

While it is increasingly understood that interoceptive disruptions are linked with mental illness and trauma, the specific patterns—such as whether they present as hyper- or hypo-sensitivity—are less well defined. The aim of this scoping review was to explore the relationship between interoception and experiences of stress, trauma, and mental illness and to determine whether they are associated with heightened (hyper) or reduced (hypo) interoceptive sensitivity.

To support clinical practice, particularly in counselling and psychotherapy, we adopted a transdisciplinary approach that spanned psychology, neuroscience, occupational therapy, and medicine. This review extends prior research focused on specific diagnoses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Leech et al., 2024), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Bragdon et al., 2021), and eating disorders (Cobbaert et al., 2024; Klabunde et al., 2017; Lucherini Angeletti et al., 2022). By taking a broader lens, we aimed to inform practitioners working with clients affected by a range of trauma and stress-related conditions, providing insights into how interoceptive disruption can shape both symptom presentation and treatment responsiveness.

Method

A scoping review was conducted using the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). The purpose of a scoping review is to map the literature related to a broad research question or topic, providing an overview of the nature of the evidence and identifying gaps in the research. Although a scoping review is less detailed than a traditional systematic review, it covers a broader conceptual range and allows for the inclusion of diverse studies from various fields and methodologies (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Davis et al., 2009; Levac et al., 2010; Peters et al., 2015). The review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines for reporting on systematic scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018).

Search Strategy and Data Sources

A systematic search of the literature was conducted to identify relevant studies published in the last 10 years, from between 2014 and October 2024. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), and CINAHL (EBSCO).

The search strategy was designed in MEDLINE (Ovid) using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords in combination with Boolean operators (OR, AND). MeSH terms interoception, stress disorders/traumatic, adverse childhood experiences, and psychotherapy were used, as well as keywords for the concepts of interoception and trauma. The search strategy was then translated for use in the other databases using the Polyglot Search Translator (Clark et al., 2020).

Two further searches to capture additional concepts identified as relevant to interoception (first: sensory modulation, integration, or regulation, and second: occupational therapy) were also conducted in the same databases. The search strategies for the MEDLINE database are provided in Appendix A.

Study Screening and Selection

References identified via database searches were exported to EndNote bibliographic management software (v.20, Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and then uploaded into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) where duplicates were removed. A two-phased process for screening was used: screening by title and abstract, followed by a full text screening. Each article was reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1. Reasons for excluding studies at full text screening were documented.

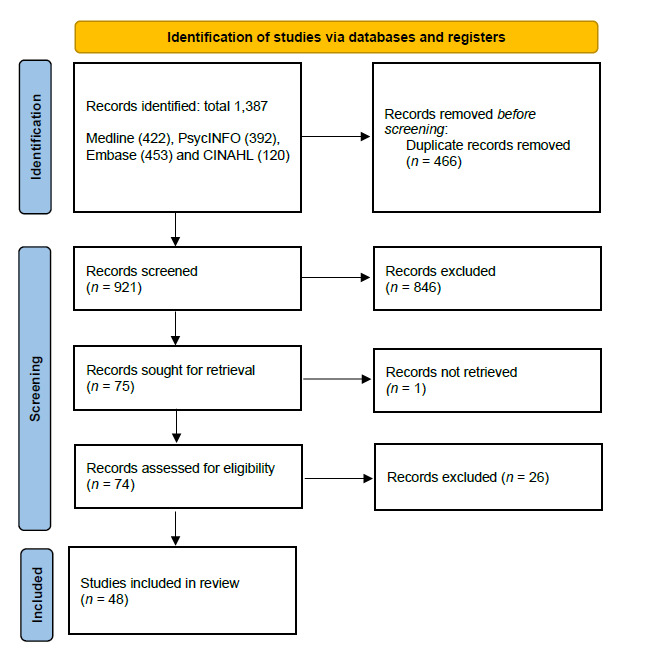

In the first instance, two researchers (SL and GB) undertook dual blind title and abstract screening and any conflicts were resolved with the project lead (DC). Dual screening continued until clarity around inclusion and exclusion was established, and the research team demonstrated confidence and consistency in decision-making. A total of 195 articles were dual screened, before moving to single screening. From this point, only studies where the researcher had some doubt around inclusion were discussed by the entire team. The screening process is summarised in Figure 1.

Data Charting

High-level data from all studies identified for inclusion were extracted using a standardised form administered in Word (DC). The study information extracted included: publication year, study aim, study design, sample/population/participant group, measurement of interoception, and results. The data were synthesised narratively, and relevant information was summarised and presented in tables. A systematic assessment of study quality was not conducted; the primary goal of a scoping review is to map the breadth and depth of available literature on a topic, and this is not considered essential (Gough et al., 2012; Tricco et al., 2018).

Results

Forty-eight studies were included in the review. As outlined in the PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1, the screening process included the review of 1,387 abstracts and 74 full text reviews. Of the 48 studies included, 17 studies regarded trauma, 14 mental health, 10 eating disorders and issues around body image, and seven physical health conditions associated with stress. A narrative description of each study is provided below, and a table of included studies is provided in Appendix B.

Studies conceptualised and defined interoception in different and inconsistent ways. While the most common dimensions of interoception measured were IAw and IAc, some studies referred to interoception in a more general sense, sometimes called interoceptive sensitivity, or used broader terms such as body awareness or body dissociation in reference to interoception. For clarity, when reporting study findings, we have used the terms adopted by the authors, and included the specific measures used in the table of included studies (Appendix B). In addition, the range of measures used to test interoception, and a description of these measures is outlined in Table 2. Neuroimaging studies mostly study interoception through measurement of the insula.

Trauma

Of the 17 studies regarding trauma, the populations studied were: people who had experienced childhood trauma (n = 5) (Lloyd et al., 2021; Schaan et al., 2019; Schmitz et al., 2023; Schulz et al., 2022; Zdankiewicz-Ścigala et al., 2018), relational trauma (broadly) (n = 1) (Scalabrini et al., 2024), intimate partner violence (n = 2) (Machorrinho et al., 2022, 2023), sexual violence (n = 2) (Poppa et al., 2019; Reinhardt et al., 2020), and PTSD (n = 7) (Beydoun & Mehling, 2023; Farris et al., 2015; Harricharan et al., 2017; Leech et al., 2024; Nicholson et al., 2016; Reuveni et al., 2018; Schmitz, Müller, et al., 2021). A further study was concerned with both childhood trauma and borderline personality disorder (Schmitz, Bertsch, et al., 2021) and is reported under mental health. Most of these studies found a relationship between trauma and reduced interoception, reporting reduced body awareness and ability to interpret bodily sensations (hypo-sensitivity).

Childhood Trauma

The five studies that investigated the relationship between interoception and childhood trauma consistently reported a relationship between childhood trauma and interoception (Lloyd et al., 2021; Schaan et al., 2019; Schmitz et al., 2023; Schulz et al., 2022; Zdankiewicz-Ścigala et al., 2018). Schaan et al. (2019) investigated the effects of childhood trauma on 66 young adults’ IAc, using a heartbeat perception task, electrocardiogram (ECG), and salivary cortisol test conducted during a cold-pressor challenge (details of all measures are outlined in Table 2). This study found a significant association between childhood trauma and IAc, especially following the stressor: the more childhood trauma participants reported, the harder it was for them to perceive their heartbeat after the stressor.

Schulz et al. (2022) investigated the effect of a stressor that activated the body’s “fight or flight” response (sympatho-adreno-medullary axis activation) on IAc using the heartbeat counting task. A total sample of 114 healthy participants with and without adverse childhood experiences (ACE) as well as unmedicated depressive patients with and without ACE were tested after drinking yohimbine (an alpha 2-adrenergic antagonist that activates the fight-flight response) and a placebo. IAc decreased after yohimbine in the healthy group with ACE, but remained unchanged in all other groups. This indicates that suppressed processing of physical sensations in stressful situations (decreased IAc) may represent an adaptive response to adverse childhood experiences.

Schmitz et al. (2023) investigated the mediating role of interoception between early trauma and emotional dysregulation and mental health impacts. Based on a sample of 166 individuals with varying levels of traumatic childhood experiences and mental health impacts, the study found that body dissociation, but not other interoceptive measures, was an important feature linking traumatic childhood experiences to current emotional dysregulation. The authors proposed that a habitual avoidance or disregard of internal bodily experiences, along with a sense of detachment from one’s own body, may reflect a focus on external stimuli as a protective strategy stemming from a history of childhood trauma.

Lloyd et al. (2021) investigated interoception in 98 adults with childhood trauma, with or without alexithymia in adulthood. Alexithymia is a subclinical condition characterised by difficulty in identifying, interpreting, and describing emotions, both in the self and others. This study confirmed the relationship between childhood maltreatment and alexithymia symptoms, and found that difficulty identifying and labelling emotions may arise, in part, from an altered perception of somatic activation and interoception. This indicates that when interoception is affected, the subjective experience of emotions, and the sensations proposed to underpin them, may also be altered significantly.

Zdankiewicz-Ścigala et al. (2018) assessed the relationship between early childhood trauma, alexithymia, and dissociation in 31 women and 25 men. This study found that alexithymia and trauma, in particular emotional neglect and emotional abuse, are significant predictors of impaired interoception. The authors concluded that traumatic experiences in early childhood become the basis for fostering permanent defence mechanisms: alexithymia and dissociation from internal experiences.

Relational Trauma—Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence

Five studies investigated the relationship between interoception and relational trauma, not specific to childhood trauma (Machorrinho et al., 2022, 2023; Poppa et al., 2019; Reinhardt et al., 2020; Scalabrini et al., 2024).

A meta-analysis by Scalabrini et al. (2024) compared the impact of traumatic experiences like natural catastrophes versus relational traumatic experiences (e.g., sexual/physical abuse, interpersonal partner violence) on the development of the interoceptive self and its related brain networks. While both forms of PTSD were associated with abnormal responses of subcortical limbic and interoceptive self-areas, comparison showed nonrelational versus relational traumatic experiences might differently affect the self-organisation of brain topography in response to emotional stimuli. The most recurrent finding among individuals with relational trauma was an increased activity of the insula, which is a key hub for emotional awareness and associated with interoception.

Two studies regarded intimate partner violence (IPV). Machorrinho et al. (2022) examined the association between interoception, body ownership, bodily dissociation, and mental health of 38 female victim-survivors of IPV. The study found that female victim-survivors of IPV experience a high prevalence of anxiety, PTSD, and depression, with these mental health symptoms being mediated by a diminished sense of body ownership and interoception. Interoceptive self-regulation and interoceptive trust (that is, the ability to regulate distress by focusing on body sensations and perceiving one’s body as safe) were linked to fewer mental health symptoms, while bodily dissociation was associated with a higher prevalence of such symptoms. The authors concluded that the tendency to distract from bodily sensations may serve as a coping mechanism, with increased bodily dissociation potentially acting as a risk factor for the development of mental health issues. A second study by Machorrinho et al. (2023), which compared 47 victim-survivors of IPV to 44 non-victim-survivors on a range of interoceptive measures, found that victim-survivors of IPV reported stronger experiences of body disownment and dissociation, although no differences in IAw and interoceptive cardiac accuracy were found.

Reinhardt et al. (2020) investigated the relationship between sexual trauma, PTSD symptoms, dissociation, and interoception in 200 female survivors of sexual trauma. This study found that interoception was negatively associated with PTSD symptoms; as IAc increased, PTSD decreased.

A neuroimaging study by Poppa et al. (2019) examined interoception-linked differences in brain networks in 43 women with a history of relational trauma and substance use disorders, 14 of whom had a diagnosis of PTSD and 29 without PTSD. Participants underwent the IN-OUT task (see Table 2) while undergoing an fMRI scan, with the magnitude of insula response during this task reflective of the quality of internal focus. This study found that there was a cumulative association between sexual trauma exposure and orbitofrontal network strength (networks associated with interoception) during interoception, independently from PTSD status.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Seven studies investigated the relationship between interoception and PTSD broadly (Beydoun & Mehling, 2023; Farris et al., 2015; Harricharan et al., 2017; Leech et al., 2024; Nicholson et al., 2016; Reuveni et al., 2018; Schmitz, Müller, et al., 2021). A scoping review by Leech et al. (2024) investigated the relationship between IAw and PTSD. Based on 43 included studies, this review concluded that the relationship between decreased IAw and PTSD is well established, and that key to this relationship is the role of IAw in an individual’s ability to regulate their emotions.

Schmitz, Müller, et al. (2021) investigated the cortical representation of cardiac interoceptive signals, called heartbeat evoked potential (HEP), in 24 patients with PTSD. This study found no significant difference in patients with PTSD (n = 24) compared to healthy controls (n = 31), although HEPs of patients with PTSD were descriptively higher.

Beydoun & Mehling (2023) assessed the relationship between trauma centrality (type and number of traumas), IAw, and PTSD symptomology in 554 participants residing in Lebanon. This study found that participants who had high levels of IAw tended to have lower symptoms of PTSD, and participants with high levels of trauma had greater symptoms of PTSD.

Farris et al. (2015) measured the relationship between PTSD symptom severity, anxiety sensitivity, and interoceptive threat-related smoking abstinence expectancies in 122 treatment-seeking daily smokers. Anxiety sensitivity was defined as the tendency to catastrophise and misinterpret the meaning of anxiety-relevant interoceptive sensations. This study found that PTSD symptom severity was positively associated with anxiety sensitivity and smokers’ interoceptive threat-related expectations about the harmful consequences and somatic symptoms from smoking abstinence. Sensitivity to interoceptive signals and associated fears are important variables in PTSD and in the maintenance/relapse of smoking.

A neuroimaging study by Reuveni et al. (2018) compared positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 12 patients with PTSD and 15 healthy controls for differences in the benzodiazepine (BZD) receptor binding potential, which includes insular regions that support interoception and autonomic arousal. This study found that patients with PTSD exhibited increased BZD binding in the mid-insular area implicated in interoception.

A neuroimaging study by Nicholson et al. (2016) compared fMRI data of 61 patients with PTSD (17 with dissociation and 44 without) and 40 matched healthy controls to investigate the functional connectivity between insular subregions (anterior, mid, and posterior) and the bilateral amygdala. This study found that both PTSD groups were characterised by aberrant arousal patterns as compared to healthy controls, but displayed opposite arousal/interoceptive symptoms. Patients with PTSD without dissociation displayed exacerbated arousal and monitoring of internal bodily states, whereas patients with PTSD and dissociation displayed attenuated arousal/interoception.

A neuroimaging study by Harricharan et al. (2017) compared fMRI data of 60 patients with PTSD, 41 with PTSD and dissociation (dissociative subtype), and 40 healthy controls to examine vestibular nuclei functional connectivity. The vestibular system integrates multisensory information to monitor one’s bodily orientation in space and is influenced by IAw. This study found reduced vestibular functional connectivity with the posterior insula in patients with PTSD compared to healthy controls. This suggests a weakened IAw and a diminished sense of bodily orientation, which may impair the multisensory integration of vestibular signals crucial for understanding one’s relationship with the environment.

Mental Health

Of the 14 studies regarding mental health, the populations studied were: people with psychiatric conditions more generally (n = 2; Millon & Shors, 2021; Nord et al., 2021), psychosis (n = 1; Damiani et al., 2024), depersonalisation-derealisation disorder (n = 1; Schulz et al., 2015), dissociation (n = 1; Schäflein et al., 2018), previous suicide attempts (n = 1; Deville et al., 2020), depression (n = 2; Dunne et al., 2021; Eggart et al., 2019), anxiety and depression (n = 1; Ironside et al., 2023), anxiety (n = 1; Garfinkel et al., 2016), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; n = 1; Bragdon et al., 2021), and borderline personality disorder (BPD; n = 3) (Flasbeck et al., 2020; Muller et al., 2015; Schmitz, Bertsch, et al., 2021). Similar to the studies specific to trauma, most of these studies reported that psychiatric conditions are associated with reduced interoception.

In relation to psychiatric conditions more generally, a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies by Nord et al. (2021) identified 33 studies, which included 610 healthy controls and 626 patients with schizophrenia, bipolar or unipolar depression, PTSD, anxiety, eating disorders, or substance use disorders. This study found disrupted interoceptive processing in the left dorsal mid-insula in psychiatric patients compared to healthy controls.

Millon and Shors (2021) assessed the relationship between mental health and IAw and IAc in 35 women using a heartbeat tracking task and MAIA-2, a self-report questionnaire assessing seven interoception dimensions (see Table 2). Women who reported greater numbers of symptoms related to mental health reported decreased ability to sense and trust bodily sensations and regulate thoughts and feelings related to these sensations.

Damiani et al. (2024) investigated the relationship between interoceptive and exteroceptive functioning in 72 patients with psychosis compared to 210 healthy controls. This study found that psychosis was associated with interoceptive and exteroceptive abnormalities; in particular, the relationship between interoceptive and exteroceptive functioning was impaired.

Schulz et al. (2015) compared IAc in 23 patients with depersonalisation-derealisation disorder to that of 24 healthy controls using HEP amplitudes during a heartbeat perception task. Although absolute HEP amplitudes did not differ between groups, healthy controls exhibited higher HEPs during the heartbeat perception task compared to the rest, while no such effect was observed in patients with depersonalisation-derealisation disorder. These findings may indicate that patients with depersonalisation-derealisation disorder have difficulty effectively focusing their attention on interoceptive signals.

Schäflein et al. (2018) assessed the IAc of 18 patients with dissociative disorders compared to 18 healthy controls using MAIA and heartbeat detection at baseline and after exposing them to their own faces in a mirror. Patients with dissociative disorders showed a considerable deficit in IAc compared to controls. The results support the idea that patients with high dissociation are more likely to disregard bodily signals.

A neuroimaging study by Deville et al. (2020) assessed interoceptive functioning of 34 individuals with a history of attempted suicide in comparison to 68 without such a history using fMRI of the insular cortex during a heartbeat perception task, breath-hold challenge, and cold-pressor challenge. Participants who had attempted suicide tolerated the breath-hold and cold-pressor challenges for significantly longer and exhibited lower accuracy in heartbeat perception compared to non-attempters. These differences were reflected in reduced activation of the mid/posterior insula during attention to heartbeat sensations. This indicates that people who have attempted suicide exhibit an “interoceptive numbing” characterised by increased tolerance for aversive sensations and decreased awareness of non-aversive sensations. This interoceptive numbing was associated with less activity in the insular cortex.

Three studies investigated the relationship between interoception and depression. A review by Eggart et al. (2019) analysed findings from six studies that reported on IAc using heartbeat perception tasks. The findings show that depression is associated with interoceptive deficits, in particular for moderately depressed individuals. While moderately depressed individuals are poor heartbeat perceivers compared with healthy adults, there is uncertainty about whether this is true for severely depressed individuals.

Dunne et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between depression and interoception in 281 patients using MAIA. This study showed a strong relationship between depression and body trusting, indicating that lack of body trust appears important for understanding how individuals with depression interpret or respond to interoceptive stimuli.

Ironside et al. (2023) investigated reactivity to an aversive interoceptive experience of 104 individuals with comorbid depression and anxiety disorders compared to 52 individuals with depression only, using the breath-hold and cold-pressor challenges, and heartbeat perception and interoceptive attention tasks. The comorbid depression and anxiety group showed significantly greater self-reported fear of suffocation during breath holding and reduced cold pain tolerance signified by hand removal during immersion. This indicates that individuals with comorbid anxiety and depression have an exaggerated response to aversive interoceptive signals and increased threat sensitivity compared to those with non-anxious depression.

Garfinkel et al. (2016) assessed the relationship between anxiety and cardiac and respiratory interoception in 42 healthy volunteers. Poor respiratory accuracy was associated with heightened anxiety score, while good metacognitive awareness for cardiac interoception was associated with reduced anxiety.

A review by Bragdon et al. (2021), specific to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), identified six studies that examined IAc and/or IAw. This review found that the subjective experience of internal bodily sensations in OCD appears to be atypical. Neuroimaging investigations suggest that interoception is related to core features of OCD, particularly sensory phenomena and disgust.

Three studies investigated the relationship between interoception and borderline personality disorder (BPD). Flasbeck et al. (2020) assessed the association of clinical correlates of poor IAw (i.e., alexithymia and dissociation) with electrophysiological markers of interoception (HEP, heart rate variability, and autonomic nervous system [ANS] functioning) in 20 people with BPD compared to 20 healthy controls. This study found that individuals with BPD had higher HEP amplitudes and greater ANS activity compared to healthy controls. These findings support the notion that challenges in emotional awareness in BPD are mirrored in changes in interoceptive markers.

Schmitz, Bertsch, et al. (2021) investigated body connection and body awareness, and their association with traumatic childhood experiences, in 112 women with BPD, compared to 96 healthy controls. Individuals with BPD reported significantly lower body awareness and significantly higher body dissociation. Body dissociation was positively associated with traumatic childhood experiences and emotional dysregulation. Additionally, body dissociation mediated the positive relationship between traumatic childhood experiences and impaired emotional regulation in the BPD group.

A neuroimaging study by Muller et al. (2015) investigated IAc in 34 medication-free patients with BPD, and 17 medication-free patients with BPD in remission, compared to 31 healthy controls, using HEPs. Patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower mean HEP amplitudes compared to controls, while the mean HEP amplitudes of patients with BPD in remission were intermediate between those of the two groups. HEP amplitudes were negatively correlated with emotional dysregulation and positively associated with grey matter volume in core interoceptive regions, such as the left anterior insula and bilateral dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. These findings suggest deficits in interoceptive processes in patients with BPD, with less pronounced deficits observed in those in remission.

Eating Disorders and Issues Around Body Image

Of the 14 studies regarding eating disorders (EDs) and issues around body image, the populations studied were: people with EDs generally (n = 4) (Brown et al., 2017; Cobbaert et al., 2024; Lucherini Angeletti et al., 2024; Monteleone et al., 2019), anorexia nervosa (AN) (n = 3) (Ehrlich et al., 2015; Lucherini Angeletti et al., 2022; Pollatos et al., 2016), bulimia nervosa (BN) (n = 2) (Chester et al., 2024; Klabunde et al., 2017), and issues around body image (n = 1) (Todd et al., 2020). Studies regarding EDs and body image were grouped together based on established theoretical and clinical links between EDs and body image disturbances.

Again, most of these studies show a relationship between EDs and reduced interoception.

Four studies regarded EDs generally. A review and meta-analysis by Cobbaert et al. (2024) investigated the relationship between ED diagnosis and interoception in 17 included studies. People with EDs reported significantly poorer interoception compared to healthy controls, with people with BN experiencing more severe interoceptive difficulties relative to those with AN or binge eating disorder.

Monteleone et al. (2019) studied the role of IAw in understanding the relationship between childhood maltreatment and EDs in 228 people with EDs (94 with AN restricting [ANR] type and 134 with binge-purging [BP] symptoms). All types of child maltreatment were connected to the ED psychopathology through emotional abuse, and this relationship was mediated by IAw for both groups. IAw plays a central role in the complex interactions between child maltreatment, in particular emotional abuse, and the core symptoms of EDs.

Brown et al. (2017) also explored the relationship between EDs and IAw with 376 adult and adolescent patients with EDs using the MAIA. This study found that individuals who were distracted from uncomfortable body sensations had a low ability to regulate distress by attending to their bodily signals and those who trusted their bodies the least had the most severe ED symptoms.

Lucherini Angeletti et al. (2024) investigated the role of interoceptive deficits in Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in 130 patients with AN and BN (using the nine-item Interoceptive Deficits subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory-3). This study found that insecure attachment and various forms of traumatic childhood experiences significantly exacerbated interoceptive deficits, which in turn are associated with Non-Suicidal Self-Injury behaviours through the increase in levels of dissociation and emotional dysregulation.

Three studies were specific to AN. Pollatos et al. (2016) investigated IAc in 15 patients with AN compared to 15 healthy controls using the heartbeat perception task. IAc was reduced in patients with AN compared to controls.

A review of neuroimaging studies by Lucherini Angeletti et al. (2022) investigating the relationship between AN and deficits in the interoceptive processing regions of the brain identified two studies that specifically investigated interoception in patients with AN. This review found that regions closely related to the processing of the self, in particular the regions associated with interoceptive processing, are altered in patients with AN. Findings suggest that AN is associated with a lack of integration of information concerning how one’s own body is perceived and experienced in the self. Interoceptive deficits may lead to high levels of distrust towards their own body and predispose patients with AN to greater top-down cognitive (mental) rigidity, in order to control their body.

A neuroimaging study by Ehrlich et al. (2015) compared resting state fMRIs of 35 unmedicated female patients with acute AN and 35 closely matched healthy controls. Results suggest decreased connectivity in a thalamo-insular subnetwork in patients with AN. This network is believed to be crucial for the propagation of sensations that alert the organism to urgent homeostatic imbalances and pain—a process that is known to be severely disturbed in AN. In people with AN, a lack of, or erroneous, interoceptive feedback might contribute to the striking discrepancy between their actual and perceived internal body state.

Two studies were specific to BN. A review by Klabunde et al. (2017) examined the relationship between BN and interoceptive processing and included 41 studies. The review identified evidence of abnormal brain function, structure, and connectivity within the interoceptive neural network, along with disturbances in gastric and pain processing. It concluded that deficits in interoceptive sensory processing may directly contribute to, and help explain, a range of symptoms in individuals with BN. These findings suggest a potential neurobiological basis for global interoceptive sensory processing deficits in BN, which may persist even after recovery.

Chester et al. (2024) tested an “interoceptive inference” model for understanding BN that proposes that BN persists because individuals under-rely on information from bodily signals and over-rely on preexisting expectations (“prior beliefs”). Compared to healthy controls (n = 31), individuals with BN (n = 30) reported lower trust in sensory information and stronger beliefs that once upset, there is little they can do to self-regulate except for eating. These findings suggest that during periods of physiological arousal, insufficient attention to sensory information and an overreliance on prior beliefs hinder effective self-regulation.

Todd et al. (2020) assessed the relationship between gastric interoception (the processing of sensory stimuli originating in the gut) and body image in 91 adults in the United Kingdom and 100 in Malaysia using the water load task. This study found a significant association between facets of gastric interoception and positive body image. This indicates that increasing awareness of satiation-related stimuli could promote body appreciation.

Physical Health Conditions Associated with Stress

Of the seven studies that regarded other stress-related disorders, the populations studied were: people with functional neurological disorder (n = 2) (Pick et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2021), fibromyalgia (n = 3) (Martinez et al., 2018; Rost et al., 2017; Valenzuela-Moguillansky et al., 2017), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (n = 1) (Atanasova et al., 2021), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (n = 1) (Longarzo et al., 2017). Fibromyalgia (Martinez et al., 2018; Rost et al., 2017; Valenzuela-Moguillansky et al., 2017), IBD (Atanasova et al., 2021), and IBS (Longarzo et al., 2017) were more strongly associated with increased interoception or a heightened sensitivity to bodily sensations, whereas functional neurological disorder (FND) is associated with dissociation or a decreased sensitivity (Pick et al., 2020).

In relation to FND, Pick et al. (2020) examined susceptibility to dissociation and the impact of dissociation on interoceptive processing in adults with FND (n = 19) and healthy controls (n = 20) before and after a validated dissociation induction procedure (mirror-gazing, where participants sit quietly and gaze into the mirror for 10 min). Individuals with FND experienced greater susceptibility to dissociation, metacognitive deficits, and impaired IAc after acute dissociation compared with controls. There was no significant between-group difference in IAc at baseline; however, the FND group displayed reduced IAc post-induction relative to controls. FND was associated with lower scores on the “Not-Distracting” and “Trusting” subscales of the MAIA, suggesting a greater tendency towards distracting from or avoiding aversive bodily experiences, alongside a reduced subjective experience of the body as safe, predictable, and trustworthy.

Williams et al. (2021) assessed interoceptive sensitivity using the heartbeat detection task in 26 patients with FND at baseline and following stress induction compared to 27 healthy controls. This study found deficits in emotional processing and lower IAc in the patient group at baseline and following stress induction.

Three studies were concerned with fibromyalgia. Valenzuela-Moguillansky et al. (2017) investigated interoceptive aspects of body awareness in 30 women with fibromyalgia compared to 29 healthy controls. The MAIA total score did not differ between the fibromyalgia and control groups. However, scores for “Noticing” were higher in the fibromyalgia group, indicating that patients are more aware of both comfortable and uncomfortable body sensations compared to controls. Additionally, “Trusting” scores were lower among patients with fibromyalgia. These results suggest that although fibromyalgia patients have heightened awareness of body sensations, they struggle to use this awareness to regulate distress.

Martinez et al. (2018) evaluated body awareness in 14 women with fibromyalgia compared to 13 healthy controls using the Rubber Hand Illusion (body ownership) and the Body Perception Questionnaire to measure IAw. Patients scored significantly higher across all three domains evaluated in the Rubber Hand Illusion paradigm, namely proprioceptive drift and perceived ownership and motor control over the rubber hand. Patients also had significantly higher scores in all subscales of the Body Perception Questionnaire, including stress responses, autonomic nervous system reactivity, and stress style, indicating increased IAw.

Rost et al. (2017) assessed IAc in 47 patients with fibromyalgia compared to 45 healthy controls using the heartbeat tracking task. Patients reported higher body vigilance than controls, but there were no group differences in IAc.

Atanasova et al. (2021) investigated the associations between interoception and emotional processing in 34 patients with IBD in clinical remission compared to 35 healthy controls, while taking ACE into account. Patients with IBD reported increased awareness of the link between bodily sensations and emotional states, while also displaying a stronger tendency to distract themselves from unpleasant sensations. ACE affect the association between interoception and emotional processing.

A neuroimaging study by Longarzo et al. (2017) investigated functional alteration of brain areas involved in interoception, for example, the insula, in 19 patients with IBS. Results show an “abnormal network synchrony” reflecting functional alteration among brain areas related to interoception.

Discussion

This scoping review confirms a consistent association between trauma, stress, and mental health conditions and disruptions in interoceptive functioning. Across a range of study designs—including meta-analyses and systematic reviews—evidence indicates that interoceptive impairment is a common feature across diverse clinical presentations (Bragdon et al., 2021; Leech et al., 2024; Nord et al., 2021; Scalabrini et al., 2024).

The majority of studies reviewed showed that these impairments typically manifest as reduced body awareness and difficulty interpreting internal sensations (hypo-sensitivity), although some variability exists. This trend was particularly strong in mental health conditions such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, and is reflected in both self-report and neuroimaging data (Beydoun & Mehling, 2023; Harricharan et al., 2017; Leech et al., 2024; Schmitz et al., 2023).

Relational forms of trauma—such as childhood abuse, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault—were especially associated with interoceptive hypo-sensitivity, often coupled with body disownment or dissociation (Lloyd et al., 2021; Lucherini Angeletti et al., 2024; Schmitz, Bertsch, et al., 2021; Schmitz et al., 2023; Zdankiewicz-Ścigala et al., 2018). This may reflect a protective or adaptive response, where survivors shift attention away from bodily sensations associated with threat, pain, or vulnerability, and redirect focus externally as a form of hypervigilance (Flasbeck et al., 2020; Schaan et al., 2019; Schulz et al., 2022).

PTSD presentations also varied depending on symptom profile. While most individuals with PTSD displayed decreased interoceptive functioning, those without dissociation sometimes showed hyper-sensitivity—a heightened awareness of bodily signals often experienced as intrusive or distressing (Farris et al., 2015; Nicholson et al., 2016).

Mental health conditions more broadly, especially those involving dissociation, suicidality, or emotional dysregulation, were similarly characterised by reduced interoception (Deville et al., 2020; Millon & Shors, 2021). This is particularly relevant in counselling and psychotherapy contexts, where poor awareness of internal states can interfere with emotion recognition, therapeutic engagement, and capacity for regulation (Reinhardt et al., 2020).

Eating disorders consistently showed impaired interoceptive functioning, especially among individuals with a history of childhood trauma or emotional neglect (Lucherini Angeletti et al., 2024; Monteleone et al., 2019). Clients with more severe symptoms often reported both greater dissociation and reduced body trust (Brown et al., 2017; Chester et al., 2024; Lucherini Angeletti et al., 2022), highlighting a key area of focus for therapeutic work.

In contrast to the general trend of hypo-sensitivity, some physical health conditions such as fibromyalgia, IBS, and IBD were associated with hyper-sensitivity (Atanasova et al., 2021; Longarzo et al., 2017; Martinez et al., 2018; Rost et al., 2017; Valenzuela-Moguillansky et al., 2017). However, even in these populations, increased interoceptive awareness did not necessarily translate to better regulation.

From a trauma-informed perspective, these findings make intuitive sense. Initially, trauma may lead to hyper-responsivity to internal states, but over time, the nervous system may adapt by dampening awareness as a form of self-protection—resulting in chronic under-responsiveness or detachment from bodily cues (Boulet et al., 2022; Price & Hooven, 2018; van der Kolk, 2014). Given the high prevalence of trauma histories among individuals with mental health issues (Schmitz et al., 2023; Scott et al., 2023), this framework has broad relevance across counselling and psychotherapy contexts.

Importantly, several studies highlighted the mediating role of body trust. A lack of trust in internal sensations was strongly associated with poorer mental health outcomes, particularly in depression, eating disorders, and functional neurological disorders (Pick et al., 2020; Valenzuela-Moguillansky et al., 2017). Trauma appears to undermine not only awareness of internal signals, but also confidence in the safety or reliability of these signals.

Reduced interoception—whether due to low awareness or mistrust—undermines self-regulation, a core focus in counselling and therapeutic practice. Without an ability to detect, interpret, or trust bodily cues, it becomes difficult for clients to identify emotions, respond to stressors, or use coping strategies effectively (Reinhardt et al., 2020).

Clinical Implications for Counselling and Psychotherapy Practice

Counsellors and psychotherapists can support clients in improving interoceptive functioning through the following strategies:

Psychoeducation: Explain interoception in clear, accessible language. Link bodily sensations to emotional states and explore how trauma may disrupt this link.

Assessment: Use tools like the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) to identify specific interoceptive difficulties and track progress (Mehling et al., 2018).

Body Awareness Practices: Incorporate mindfulness, body scans, yoga, or somatic check-ins to help clients recognise and label internal sensations (Ali et al., 2023; Ardi et al., 2021; Bryan et al., 2022; Casals-Gutierrez & Abbey, 2020).

Emotional Regulation Skills: Help clients connect sensations to emotions and develop personalised regulation strategies that promote safety and calm (Mahler, 2015).

These strategies are especially relevant for trauma survivors, for whom reconnecting with the body can support emotional resilience and healing (Ogden et al., 2006; Price & Hooven, 2018).

While the strategies outlined above can support interoceptive functioning, it is essential to adapt these approaches sensitively for trauma survivors, First Nations peoples, and individuals from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. For some clients, reconnecting with the body may evoke distress or conflict with cultural norms around bodily awareness and expression. Practitioners should approach these interventions with cultural humility, seek supervision or consultation where needed, and co-create strategies that align with the client’s values, safety needs, and lived experience. Further research is needed to explore how interoceptive interventions can be adapted for use with First Nations peoples and CALD communities. Understanding how cultural frameworks shape bodily awareness and emotional expression will be critical to ensuring that interoception-based practices are safe, respectful, and effective across diverse populations.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. The search was limited to selected databases and search terms, and grey literature was not included. Some primary studies may have been double-counted if included in both individual analysis and prior reviews. Additionally, no formal quality appraisal of included studies was conducted, consistent with the scoping review methodology. Another limitation concerns the inconsistent definitions and measurements of interoception across studies, which complicates direct comparisons. Further research is needed to refine the conceptualisation and operationalisation of interoceptive domains. Finally, this review did not include analysis of cultural or country-level differences in interoception. The decision to exclude these variables was based on the scope of the review, which focused on clinical presentations rather than sociocultural factors. While cultural influences on interoception are an important area of inquiry, they were beyond the aims of this review. This limits the generalisability of findings across cultural contexts, and future research could usefully explore how interoceptive processes vary across populations and settings.

Conclusion

This review highlights a consistent relationship between trauma, stress-related conditions, and impaired interoception. Most mental health conditions and experiences of relational trauma are associated with reduced interoceptive sensitivity and trust, with significant implications for emotional regulation, and counselling and psychotherapy outcomes. A trauma-informed lens helps make sense of these findings: avoiding or disconnecting from the body can be a protective strategy, but one that undermines self-awareness and coping. Helping clients rebuild awareness and trust in their bodily sensations may be a critical step towards recovery. While initial clinical directions are offered here, further research is needed to determine which interventions most effectively improve interoceptive functioning, and in turn, mental health outcomes.