Since Wayne Blackmon (1994) published his case study using Dungeons and Dragons (D&D, Mearls & Crawford, 2014) in a psychotherapeutic context, many papers have surfaced identifying the use and benefits of tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs) in therapy (Daniau, 2016; Enfield, 2006; Gutierrez, 2017; Kupferschmidt, 2020; Mendoza, 2020; Smith, 2013). Specifically, benefits have been associated with interpersonal and social skills, problem-solving, decision-making, story and character development, identity and self-esteem, and emotional expression (Kato et al., 2012; Raghuraman, 2000; Rosselet & Stauffer, 2013; Spinelli, 2018). Despite the emergence of this literature, limited research has been presented regarding its application in a child protection setting or an Australian context. Given the potential benefit to supporting children open to child protection services, a case study using a TTRPG was undertaken and is presented here.

The primary intention of the paper is to present a faithful retelling of an imaginative and heroic campaign, written by Oliver, facilitated in collaboration with his child protection counsellor, and then played out by himself, his older brother, younger sister, and their nanna (grandmother). First, a background to the study provides the therapeutic context and then describes TTRPGs, narrative play therapy, and the role of the therapist as co-creator and dungeon master (DM). Second, the paper discusses the process of Oliver collaboratively developing a TTRPG campaign with his counsellor. Third, the paper presents a faithful retelling of the campaign as played out by Oliver, his siblings, and their nanna, and facilitated by Oliver’s counsellor. Finally, the paper undertakes clinical reflection on the symbolism in the campaign using symbolic narrative analysis and presents the quantitative and qualitative therapeutic outcomes before offering concluding remarks.

Signed written consent was obtained by Oliver and his family to present their campaign and additional information. De-identification was undertaken, and all participants’ real names have been replaced in this paper with their fictional campaign character names. Documentation of the campaign itself was undertaken during the intervention as part of the process. Symbolic analysis and analysis of therapeutic outcome measures were undertaken after the work had been completed. This case report along with signed consent forms were submitted to the Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District (NBMLHD) research office and reviewed by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HRED). In accordance with section 5.1.22 of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2007, updated 2018), this case report was exempt from further ethical review. The author/counsellor, Oliver, and his family members all identify as white, non-Aboriginal Australians.

Background

Therapeutic Context

Oliver was referred to Child Protection Counselling Services (CPCS) by the Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ). CPCS offers individual and family-based counselling to support children, young people, parents, and carers experiencing psychological distress and instability because of child protection concerns. Oliver was referred to support him through the experience of being placed under the care of his grandparents owing to concerns about his welfare—including domestic violence and parental substance abuse—while under the care of his parents. Oliver presented as socially withdrawn both within the family and among his peers, and he communicated little with his grandparents regarding his day-to-day experiences. He also presented with emotional distress, including frequent experiences of being upset, fearful, and disinterested, as well as hypervigilance in social situations. At the time of this work being undertaken, Oliver and his siblings were under the full-time care of their grandparents; however, they were in the process of being restored to their mother’s care. This restoration has since been successful. The children’s ongoing contact with their father was limited and supervised owing to the conditions of an Apprehended Violence Order.

Tabletop Role-Playing

A TTRPG is a game facilitated by a DM in which players take on a created character and collectively embark on fantasy-based quests, attempting to meet challenges and solve problems through creative and collaborative means (Brown, 2018; Mendoza, 2020). Each player describes their actions through speech, and the success of these actions is “determined by a system of rules and guidelines, most commonly involving dice” (Spinelli, 2018, p. 7). One of the most popular TTRPGs is the fifth edition of D&D, whose structure, characters, and gameplay are set out in the Dungeons and Dragons: Player’s Handbook (Player’s Handbook; Mearls & Crawford, 2014). Table 1 provides a glossary of useful terms.

The Counsellor as Dungeon Master

Throughout the gameplay of Oliver’s campaign, the author/counsellor adopted the role of DM. A DM essentially “runs the game”, acting as a moderator of rules and narrating the ongoing progression of the story, including describing the scenes; directing and documenting actions; facilitating battles and tracking their outcomes; and playing the roles of monsters, villains, and any non-playable characters (NPCs; Wyatt et al., 2009, pp. 12, 32–44). An integral part of the DM position is to document the battles as they progress as well as the story-based action to recap at the beginning and end of each gameplay session (Cook et al., 2003). This was part of the author/counsellor’s responsibility as a DM while facilitating the game with Oliver and his siblings. Specifically, the author/counsellor needed to know the general plot line Oliver had created, have a thorough working understanding of the battle progression, and be able to log attacks while in battle and record players’ actions and decisions throughout the gameplay. The documented campaign episodes and the battle tables (see Tables 4–6) are presented in the “Playing the Campaign” section further below. These records were re-read at the beginning of each session and presented to Oliver as therapeutic documentation at closure.

Narrative Play Therapy

Complementary to the use of TTRPGs in therapy, Ann Cattanach (2006) describes how in narrative play therapy stories are used “as a way of helping children express and explore their experiences of life” and hence “facilitate an exchange of ideas and thoughts about such stories” (pp. 83–85). When children tell stories, they represent not only experiences they know but also experiences they would like to know; therefore, the imaginative control they employ, at least symbolically, can help develop their ability to communicate and their sense of agency and identity (Cattanach, 2007, 2008).

Within the therapeutic storytelling process there are two roles—a storyteller and a listener—and each role has an equal function in the co-construction of the story as it emerges between the two (Cattanach, 2006). In this way, the unfolding of a story between the interaction of a child and a therapist is always a collaborative co-authoring (Lax, 1992). The collaborative role of a therapist then is to attend, listen, and serve the story being told, to ask questions about the story as it develops, to record aspects of the story, to engage actively in telling the story, and to promote the opportunity for further telling and retelling (Cattanach, 2007).

The Counsellor as Co-creator

As a counsellor within CPCS, the author has been trained to engage in narrative-based therapeutic practices with children and young people. To engage in narrative practices is to take a political stance attempting to address “therapeutic governance”, that is, the way in which “psychosocial and therapeutic programs inadvertently impose certain understandings of life, trauma and healing” (Pupavac, 2001, p. 367). As a narrative practitioner, the author attempts to maintain a “decentred but influential” position when working therapeutically (White, 2005, p. 9). White (2005) defines decentred as “according priority to the personal stories of each individual”, giving them “primary authorship status” (p. 9), and taking into consideration their own personal insider skills and knowledges. Additionally, he defines influential as using therapeutic scaffolding to help individuals richly develop the alternative stories of their lives (White, 2005). With these practices in mind, the counsellor attempted to engage with Oliver as a co-creator in the therapeutic process, drawing on or “leaning into” Oliver’s presented interests to inform the therapeutic process and serve as a collaborative storyteller. This process is outlined in the next section, “Creating the Campaign”. It is important to acknowledge the primary authorship status of Oliver in this process, which has informed this paper’s intention to present a faithful retelling of Oliver’s campaign.

Creating the Campaign: Characters, World-Building, and Quests

The first time the counsellor met Oliver, he identified D&D as an interest of his. Having some understanding of the game, the counsellor asked, “Is it right that D&D is all about campaigns?” Oliver stated that “it is”. The counsellor then followed up by asking, “What is it that makes a good campaign?” Oliver replied, “Good characters, good locations, and good quests”. The counsellor took note and asked whether perhaps next time they met, Oliver might be able to bring some resources for them to build a campaign, with the intention of playing it with his siblings. He agreed and stated that his siblings would be interested.

Characters

At the second meeting, Oliver came equipped with a small library of D&D books ready to begin planning. Using the Player’s Handbook (Mearls & Crawford, 2014), Oliver and the counsellor created four playable hero characters inspired by Oliver, his two siblings, and their nanna. Together, they completed specific parts of the character sheet (p. 317), assigning each character a name, race (pp. 17–42), class (pp. 45–112), armour (p. 144), weapons (p. 146), spells (pp. 207–2011), and Hit Points, strength, and dexterity statistics (pp. 12–13). At the end of this session, Oliver began analysing the D&D Monster Manual (Mearls et al., 2014) and Mordenkainen’s Tome of Foes (Mearls & Crawford, 2018), where he identified several monsters he wanted to appear in the campaign, and he and the counsellor modified their statistics to align with the heroes’ levels. (See Table 2 for playable characters’ and NPCs’ information.)

World-Building and Quests

At the third session, Oliver noted that it is important for characters to have a back story. He explained that his and his two siblings’ characters lived in the same village, which had been overtaken by a dark force resulting in their displacement into another world. The full description of these characters’ back stories became the prologue of the campaign, which is presented in the next section. Once the prologue had been outlined, Oliver and the counsellor found an image of, first, a village map with a well in the centre and, second, a map of a dungeon. Oliver explained that the well would be an entrance point to the dungeon, where a magical wand would be hidden in its depths needing to be retrieved. Oliver highlighted the importance of the wand as a primary object that the characters needed to work together to obtain. The discussion on the importance of obtaining this object clarified the title of the campaign for Oliver, namely, “The Wand in the Well”.

Continuing to build on this world, Oliver and the counsellor discussed how the characters would have a “problem” that needed solving, and that each problem would align with a “quest” on which the heroes could embark to solve. Oliver identified that the primary quest of the three heroes would be “to get back to their home village” and that they would achieve this by retrieving the wand within the dungeon. In addition, they discussed how some quests might often conflict between characters and that the players would be responsible for choosing one of numerous solutions. For example, Oliver detailed that the quest of the Old Man in the village was to ask them to retrieve a magical wand from a dungeon and give it to him. In contrast, the Old Woman in the village wanted the heroes to find and give the wand to her. Alternatively, if retrieved, the heroes might choose to keep the wand for themselves. Oliver and the counsellor continued to develop these quests and devised numerous possible outcomes that might be chosen by the players throughout the gameplay.

Final Preparations

In the final individual session with Oliver, he and the counsellor completed preparations for the campaign by clarifying the possible narrative sequences on which the players might embark and when they might encounter monsters to battle. Using several resources, they developed translation puzzles to unlock dungeon doors that were based on Elvish and Draconic alphabets. They also printed several images to represent each character and key items. These were used as interactive, visual representations of the story as it progressed. Additionally, they clarified the battle progression they would use throughout the campaign.

Although inspired by the gameplay of D&D, the campaign was not played strictly by these rules; rather, a simplified version was adapted to meet the time restrictions and players’ ages and abilities (see Table 3). Once these preparations had been undertaken, they were ready to invite Oliver’s siblings to play at the next session.

Playing the Campaign

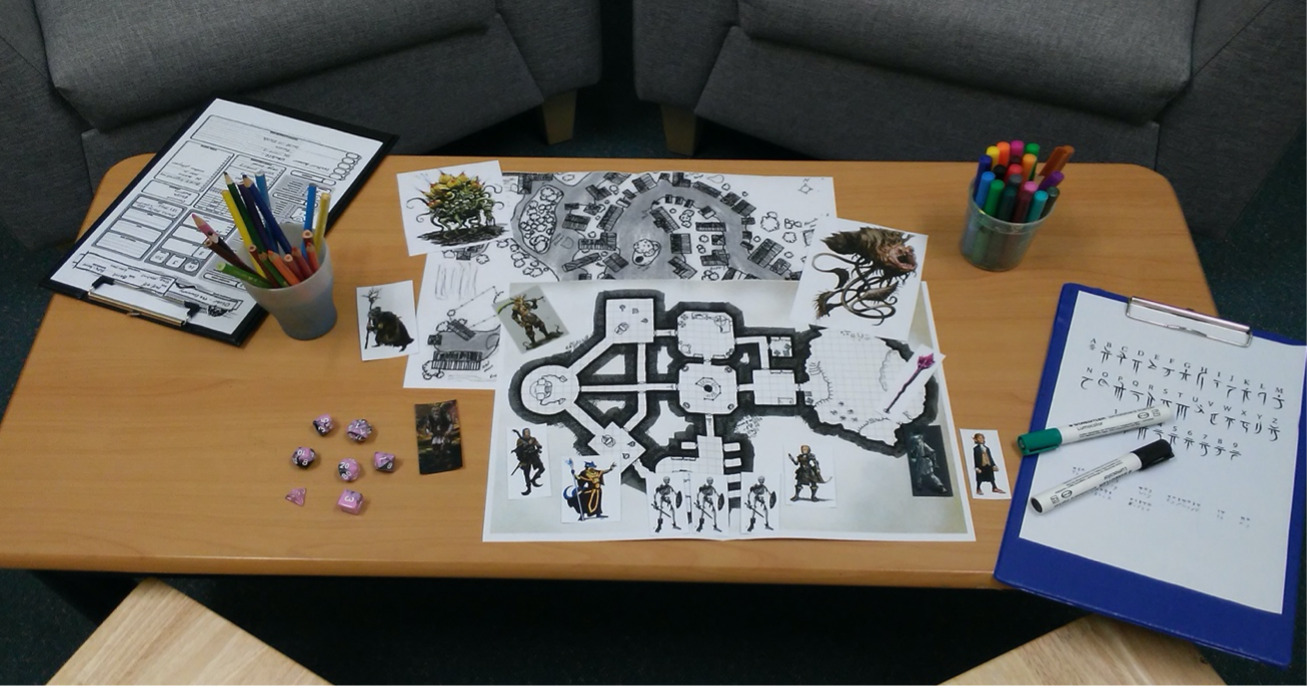

Over the next three sessions, Oliver’s siblings and nanna were invited to attend and play through the campaign. The room was set up with visual representations prepared in the previous session, including village and dungeon maps, characters, and monster images, as well as dice, writing material, and player clipboards outlining character information (see Figure 1 for tabletop gameplay setup). As DM, the counsellor had a printout of the storyline, which was amended as the characters performed specific actions and made decisions throughout. The counsellor also had battle tables to complete as the battles progressed (see Tables 4–6 for examples).

The structure of this campaign was written to span three sessions or “episodes”, and each session continued from the last, resolving to a conclusion on completion. This structure of a campaign that spans a number of sessions with continuing characters is known as a “one-shot” campaign. In contrast, a “standalone session” is a one-off, single session campaign with characters created for that one session, while a “continuing campaign” can span numerous months, potentially years, with the same characters undertaking numerous campaigns (Wyatt et al., 2009, pp. 104–107). At the end of each session, the gameplay documented was written up and recounted at the beginning of the next session/episode as a reintroduction to the campaign. Throughout this process, the family members were able to communicate and work collaboratively to complete puzzles and overcome obstacles and monsters. They were able to make collective decisions on what they should do as a group to solve specific quests. At the start of the campaign, the counsellor introduced each of the characters and read out the prologue to begin the game. Upon completion of the campaign, the children co-created the epilogue of the story.

The Wand in the Well

Prologue

Oliver, Lance, and Evie all lived in the same home village. Oliver and Lance were village soldiers, while Evie was a professional flower picker and ventured off into the forest every day to pick flowers.

One day a mysterious and evil abyss appeared, and a swarm of monsters raided their home village. Lance tackled the swarm head on, and since then has been known as Lance: The Warrior. Lance attempted to hold the creatures off, but they were too numerous, and he was pulled into a portal. Oliver ran in the opposite direction of the swarm and has since been known as Oliver: The Cowardly. While Oliver was running, he accidently tripped when a portal appeared, and he fell into it. Evie Tealeaf was out flower picking when a portal appeared in front of her. Through the portal she could see the most beautiful flower, so she stepped through the portal attempting to pick it. Their home village had been overtaken by an evil force that had built an abyss castle where their village had once stood.

Episode 1: Down the Well

Oliver, Lance, and Evie woke up in a strange new location in a parallel village. Lance woke up near the house of an Old Man.

“You there! You, you are a hero, yes?” said the Old Man.

“Sure,” Lance replied.

“Please, I need your help. I was once a great and powerful wizard. But I have lost my wand. It is somewhere in this village, but I don’t know where. Will you help me? Could you please find the wand and return it to me?”

“Sure,” Lance replied again, thinking that he would most likely keep such a wand for himself.

Oliver woke up on the other side of the village near the house of an Old Woman.

“Hello! Who is that?” the Old Woman said.

“I am Oliver.”

“Oh, are you strong and brave?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Please, can you help me? I have lost my wand, and I don’t know where it has gone. If you find it, could you return it to me?”

Oliver thought for a minute.

“Sure, if I happen to come across it, I will bring it back to you.”

Evie Tealeaf woke up in the clutches of a monstrous Corpse Flower. Evie let out a terrified scream, “Eeeeeeeee!” Both Oliver and Lance ran towards the sound. There they found Evie attempting to battle the Corpse Flower. Oliver and Lance quickly joined the battle (see Table 4 for battle details).

The heroes fought valiantly against the Corpse Flower. Both Evie and Lance were close to defeat, but Oliver was able to help them with his healing spell. At the last moment, Lance administered the final blow and the Corpse Flower exploded into a thousand rainbow roses. Evie quickly picked them all.

Suddenly, the Mayor of the town came running towards them.

“Thank you for destroying the Corpse Flower! It has been causing this town problems for a very long time. Thank you. I say, what are three heroes like yourselves doing in this village?”

“We are not too sure. I met an Old Man. He said he had lost his wand,” Lance disclosed.

“I met an Old Lady,” Oliver added.

The Mayor became uneasy.

“Oh, don’t listen to them. They are bonkers crazy! They have this idea that they are sorcerers who lost their powers. What a load of nonsense. There are these ridiculous stories about the well at the centre of the village. No one has been down there in centuries. There is nothing down there other than a few rats and an old boot. It is not worth anyone’s time. Well, I must away, I have Mayor duties to attend to. Thank you again for your assistance.” The Mayor acknowledged them once again, and then disappeared as quickly as he arrived.

“What do we do now?” Oliver inquired.

“We check out the well!” Lance said, as though that was obvious.

Upon arriving at the well, the heroes saw a giant boulder sealing it from the top.

“I can break it!” Lance declared. With a vigorous head movement towards the sky and then a swift downward force, Lance crashed his forehead onto the boulder, smashing it into a million pieces.

The heroes looked down the well. It was pitch black and they could not see how deep it was. Evie cast the spell Sacred Flame, and the well was filled with light, but not quite enough to see to the bottom.

“I am just going to jump in!” Lance decided. “Ahhhhhhhh!”

Lance continued to fall and fall and fall. At the last moment, Oliver cast the spell Feather Fall, and Lance landed at the bottom of the well with a soft thump.

“I’m going in too,” Oliver shouted. “Ahhhhhhhhh!”

Lance cast the spell Mage Hand, and as he did a magical hand appeared in mid-air, grabbed Oliver, and placed him gently on the ground. Evie decided to make a chain with the flowers she had picked earlier. She was able to climb halfway down the well but was left hanging onto the last flower. Lance quickly cast the spell Mage Hand again, which picked up Evie and dropped her on top of Lance and Oliver with a thud! The heroes had made it to the bottom of the well.

Episode 2: The Dungeon

The three heroes found themselves at the bottom of the well. The only sound they could hear was the slow dripping of water along the walls. Evie Tealeaf cast the spell Sacred Flame and a square room was illuminated. Four doors were presented around the room. Oliver checked two doors but found they were sealed shut. Evie checked a third, which was also locked tight. Lance headed south to the final door and pushed it open with brute force. The three heroes entered a crypt. They looked around to see a number of tombs with skeletons in them. Suddenly, three skeletons became animate, picked up swords, and headed straight for the troop! (See Table 5 for battle details.)

The heroes fought fearlessly against the skeletons. Although taking a significant blow, Oliver used his shield enchantment, Banana Bread, and fought back to vanquish a skeleton. Evie used her crossbow and fireball to defeat a skeleton swiftly. Lance, with a large swooping attack, made short work of the final skeleton.

As the crypt became still and quiet, the heroes heard a clank as a door behind them unlocked. Eager to explore the crypt, Evie made her way through a small passage in the wall. She entered a room with one large and three smaller machines. She was not sure what the machines did or why they were there.

Oliver backtracked into the previous room and found that one of the doors had opened. He looked down the corridor and was sure he saw the Mayor of the village quickly run away into another chamber. Curious, Oliver ventured down the corridor and found a laboratory with a giant machine. The machine appeared to have an important piece missing.

Evie continued through another corridor that met up with the laboratory, where she found Oliver. Lance followed, joining them in the laboratory.

As they looked around, the heroes found a notebook on the floor. Oliver quickly read through the notes, discovering that the two smaller machines in the other room were Choker Transformation Devices, which are able to turn people into monstrous Chokers. The giant machine in the laboratory was a Choker Reverse Device, which is able to transform people back. On further examination, they found three loose pages with three inscriptions in different languages, one in Draconic, one in Elvish, and one in Halfling.

The heroes explored the chambers further, taking one corridor that led them straight back to where they had started. Making another attempt, the heroes found a new passage, which led to a locked door. In the door was a hole for a key, and a Halfling symbol was written just above it. Evie looked at the Halfling inscription in the book, which showed a picture of an arrow pointing upward, and a table next to it.

In her attempt to translate the symbols, Evie stood on top of a nearby table and looked around. Nothing. Looking again at the inscription she realised that the arrow was pointing under the table. She quickly hopped down and crawled below. There, she found another inscription. This one presented a house and an arrow pointing up and to the left.

Looking around, Evie found a small playhouse in one corner of the room. She looked inside but did not find anything. She then looked around the outside of the playhouse and found a golden key wedged behind it.

“I found a key!” Evie announced, as she put it into the lock and turned.

The door opened, and the heroes made their way through another corridor and were met with another door. On inspection, the heroes found this one had an Elvish symbol written on it and a number keypad. Oliver took a closer look, and on touching the symbol he had a vision of three siblings from a parallel world. They seemed very familiar to Oliver, as though he knew all about them. Emerging from the vision, he attended to the Elvish inscription in the notebook and translated it: “Youngest Day, Middle Month, Oldest Year”.

Oliver wondered what the vision and inscription had to do with each other. Then, he realised it referred to the day, month, and year of the siblings’ birth dates in the other world. He quickly typed in their birth dates and the door opened.

Before too long, the siblings were stopped by a third and final door; this one had a symbol of a dragon on it. Lance looked at the Draconic inscription, translated it, and read it out loud: “The only way forward is to go back first”. The heroes began to backtrack to look through the previous corridors and rooms, but they found nothing.

“It’s hopeless,” Lance said, as he patted Oliver on the back to attract his attention.

“Your back! That’s it!”

Lance ran back to the Draconic door, and instead of walking forwards, he walked backwards through it.

“It worked!” he yelled from the other side and encouraged Oliver and Evie to follow him through.

The heroes looked around the large chamber they had entered.

“There!” Evie pointed. “It’s the wand!”

Residing on the other side of the room was the most beautiful wand. It seemed to be covered by a mechanical force field. Suddenly, they saw the Mayor in the room.

“Are you okay?” asked Oliver.

“Don’t even think about taking my wand!” the Mayor warned.

“Your wand?” the heroes said in unison.

“Yes, my wand! For I am not a mayor at all!” he stated, revealing himself as an Evil Scientist.

“I have taken control of the village and have been doing scientific experimentation, and you’re not going to stop me!”

With that the Evil Scientist pulled on a rope and released a Giant Balhannoth creature from above! The creature had large tentacles and razor-sharp teeth.

“Good luck trying to stop us!” the Evil Scientist said through a shrieking cackle.

Although menacing, the Evil Scientist’s laugh was drowned out by a THUMP and then a THUD. The heroes looked behind them and saw the elf barbarian, Elfie Barb (played by Nanna), who had been watching over them the whole time. She let out a roaring laugh, and the heroes were unsure whether she was a friend or a foe.

Episode 3: The Wand in the Well

Surrounded, the heroes readied themselves to fight on all sides, caught between the Evil Scientist, the Balhannoth, and Elfie Barb. At that moment, the Evil Scientist drew a quantum ray gun and shot the heroes and Elfie Barb into a quantum trap. The heroes were transported to a room in a parallel reality suspiciously similar to the room the players were playing in.

An assortment of objects filled the room around them. The first thing Lance noticed was an envelope with Draconic script on it. He translated it to “What has hands and a face but cannot smile?” The heroes contemplated what the answer might be. The room fell silent.

“What about a clock?” Elfie Barb grunted, to the others’ surprise.

Oliver looked around the room and found a clock high up on a wall. He looked behind it to find another envelope with the words “3. Stasis” and another clue leading them to a flag. There, they found a third envelope stating “5. Diminish”, presenting another object to find. Evie continued swiftly on the trail finding one clue after another, each paired with a number and a word: “6. Void”, “1. Force”, “4. Cease”, “8. Release”, “2. Be Gone”, and “7. Heroes”. Oliver pieced together the words in order. Together, the heroes recited the incantation: “Force be gone, stasis cease, diminish void, heroes release”.

As they finished uttering the final words, the quantum trap disappeared, and the heroes were transported instantly back to the dungeon. The Evil Scientist gasped in amazement, “I never thought you would escape!”

“Well, you shouldn’t have left clues on how to get out,” replied Oliver.

“Attack!” the Scientist commanded (see Table 6 for battle details).

At the beginning of the battle, it was unknown whether Elfie Barb was an ally or an enemy. She began attacking anything and everything, including the heroes. She was then hit by the Balhannoth and she decided to attack it directly. The heroes fought courageously. Oliver and Lance targeted the Evil Scientist. Evie fought the Balhannoth and single-handedly reduced its health to three Hit Points. With a final thunder wave from Lance, the Evil Scientist and the Balhannoth were defeated.

The Scientist fell to the ground and Oliver tied him up to ensure he did not escape. The force field around the wand disappeared, but at that moment a band of Chokers crept out from the shadows and retrieved it. The Chokers were small, greyish-black, human-like creatures.

“Hey, that is our wand!” Lance cried, as he started swinging his staff but missed.

“Yeah, it’s ours!” Oliver added, who tried to swing his axe, but also missed.

The Chokers pleaded with the heroes, “Please help us. We are villagers from above, but we have been transformed into Chokers. Please will you take us to the machine that will turn us back to humans?”

Evie quickly searched the chamber and found the missing part of the Choker Reverse Device. She led the Chokers back to the device. One by one, she helped transform them back to their human form. The Chokers gave Evie the wand in return.

Epilogue

The heroes returned to the village, where they met with the Old Man and Old Woman. They discussed what they would do with the wand. The heroes’ first thought was to keep it for themselves, but the Old Man and Old Woman presented another option.

“If you give the wand back to us, we promise to give you each a wish, clear your village of the evil abyss, and give you safe passage back home.”

The heroes pondered for a moment and decided to give the wand back to the Old Man and Old Woman. With a touch of the wand, the pair were instantly turned back into King and Queen Sorcerers.

“Thank you, brave heroes! What do you wish for?”

“I want to have the power to change percentages and probabilities!” Lance affirmed.

“It shall be done.”

“I want a bear!” Evie exclaimed. “A rose-coloured bear that will protect us. I will be able to ride it and talk to it and it can talk to me!”

“It shall be done.”

“I want to be able to shapeshift,” Oliver decided.

“It shall be done.”

“I will shapeshift too,” Elfie Barb confirmed.

“And so it shall be.”

The heroes returned to their home village. Upon their homecoming, a great celebration was held to mark the return of peace to their village. To commemorate their actions, the heroes were all given new names.

Elfie Barb became known as Elfie Barb: The Mysterious, or Elfie Barb: The Traitor Who Turned Out to be Okay in the End, I Guess.

Lance became known as Lance: The Lucky.

Evie Tealeaf became known as Evie Tealeaf: The Destroyer.

And Oliver became known as Oliver: The Brave.

Symbolic Analysis of the Campaign

Tabletop Role-Playing Game Symbolism and Identity

DeLoache (1995) defines a symbol as an “entity that someone intends to stand for other than itself” (p. 67), and therefore it has the characteristic of “dual representation” (pp. 109, 111). Norton and Norton (2006) state “the purpose of identifying the symbolism of a child’s play is to enhance the meaning of his or her expression” (p. 35). Drawing on Jungian depth psychology, which emphasises the “personal significance that symbols play within a larger system of meaning”, Bowman (2007, p. 7) examines how TTRPG participants experience a “symbiotic relationship” with their characters (Bowman, 2007, p. 7). Through this relationship the participants are able to explore possibilities unavailable to them in the “real world” (Bowman, 2017, p. 160). This “creative output” not only serves the game world but also provides an embodied alternative identity in the real world, fulfilling emotional needs by providing players with the possibility of mastering skills and exerting influence and control they would otherwise be unable to achieve (Bowman, 2007, pp. 7–11). In this way, symbolic play is a “construct of reality, a reality that the child can control and change for their benefit or well-being” (Norton & Norton, 2006, p. 36).

Symbolic Narrative Analysis

Although formal qualitative analysis was not undertaken, the theoretical underpinnings of narrative analysis were considered. Narrative analysis is a discursive approach to analysing data based on the idea that people make sense of and communicate their experience in the form of stories and storytelling (McLeod, 2001). By applying concepts of symbolism and narrative analysis, it was the author’s intention through clinical reflection to identify possible symbolic identifications in the campaign.

Although symbolism is often highly interpretive and has multiple possible interpretations, the intention of this case study was to present possible representations, which were discussed throughout clinical reflection. This process consisted of first identifying the predominant symbols within the campaign, labelled “narrative symbols”. Secondly, using the information known and discussed with Oliver about his real-world experiences, “possible real-world correlates” were identified and matched with the identified narrative symbols. The resulting table presents the narrative symbols identified and their possible real-world correlates within the Wand in the Well campaign (see Table 7).

Therapeutic Outcomes

It is standard practice within CPCS to undertake quantitative outcome measures before and after the therapeutic intervention to assess improvement in psychological symptoms. Additionally, qualitative reflections are often obtained from participants or support people. Oliver’s outcomes demonstrate the real-world therapeutic impact of this intervention on Oliver and support the role of symbolic narrative construction and TTRPG within a therapeutic context.

Quantitative Outcome Measure

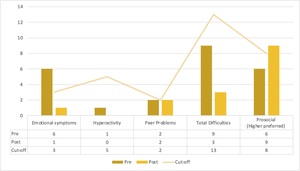

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was completed by Oliver’s nanna regarding Oliver at the beginning (pre) and end (post) of this campaign. The SDQ is a 25-item questionnaire measuring emotional and behavioural symptoms of children and young people along the subscales of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behaviour (Goodman, 2001). At the beginning of the process, the scores indicated high for emotional symptoms and low for prosocial behaviour. On completing the process, the emotional symptoms score fell below the “close to average” cut-off score and the prosocial score was above the “close to average” cut-off score. A decrease was also noted in hyperactivity symptoms and total difficulties overall (see Figure 2).

Using the Reliable Change Index (RCI) of ±1.96 (Jacobson & Truax, 1991; Zahra & Hedge, 2010), with an alpha coefficient of 0.81 for total scores and 0.71 for subscales (Achenbach et al., 2008), reliable change was demonstrated for total difficulties (RCI = −8.85), emotional symptoms (RCI = −7.82), hyperactivity (RCI = −2.87), and prosocial behaviour (RCI = 4.47). The scores for conduct problems were zero for both pre and post stages and therefore were not included.

Qualitative Outcomes

Once the campaign had been completed with Oliver and his siblings, follow-up discussions were undertaken with Oliver’s nanna and his DCJ caseworker to reflect on improvements they had noticed in Oliver. The DCJ caseworker and Oliver’s nanna gave permission for their reflections to be presented in this paper. Oliver’s nanna offered these reflections on his development:

Oliver has really come out of himself. At home he has been able to assert himself more and communicate his wants. In certain social setting and interactions, he can still be a bit withdrawn, but when he is in the game with his brother or friends, he is not withdrawn at all. He just gets excited and is laughing and joking, which was not really there before. He has really found an interest that he is drawn to, which has really increased his confidence. He started high school this year and has been able to make new friends who share the same interest. It is like he has found a place where he can be comfortable to just be himself.

Oliver’s DCJ caseworker noted:

When I first started working with Oliver, I noticed him to be a quiet, withdrawn young boy whose voice was often not heard amongst his two much louder and outgoing siblings. Oliver was always timid and shy and would not often make eye contact when speaking with someone. He spent a lot of time in his room and often went with the flow. He struggled to find his own voice within the family. When I had talked to him about engaging in counselling, he was really hesitant. With some extra encouragement and asking him to give it a chance he agreed to attend. Within the first few sessions of Oliver attending, I noticed him talking about “D&D” as well as the different roles he had assigned to each family member. I could see that Oliver already felt like he had a bit of control and was the leader for once in his family. Oliver is not the same young boy I met three years ago. He often leads conversations [and] he has developed such a strong personality, his siblings and mother would refer to him as charismatic and funny. Oliver has also been able to express his thoughts and feelings much easier with me; if he hasn’t been sure of something, he is now not afraid to ask me, and because of this we have been able to meet his needs.

Concluding Summary

In line with the intentions presented, this paper first provided the background to the study by introducing the therapeutic context, the concepts of TTRPGs and narrative play therapy, and the role of counsellor as both co-creator and DM. Then, the paper described the process of developing a TTRPG campaign and provided a faithful retelling of the Wand in the Well campaign. A clinical reflection on symbolism within TTRPGs and within the Wand in the Well campaign was presented through symbolic narrative analysis. Finally, therapeutic outcomes were presented to highlight the impact of the intervention and to support the role of TTRPGs within a therapeutic context.