Acknowledgement

I live, work, and have written this article in Boon Wurrung Country on the unceded lands of the Yallock Bulluk people, to whom I pay my deepest respects. I am conscious of the rich and strong life-enhancing traditions of arts, culture, caring, and healing practices that pulse through this living and ever-changing environment and its people, and I welcome the influence this Country has on me when I pay attention.

Foreword

Boon Wurrung Elder and language specialist, Aunty Fay Stewart-Muir, teaches that, in traditional Boon Wurrung language, “yana-bul ngarnga-dha” means “you are hearing/listening”. She says, “This is very important when the Elders are passing on knowledge to children. If you don’t listen you miss part of the story and it won’t be repeated” (Stewart-Muir, 2022).

As a researcher, I am inspired by the Indigenous healing practice of deep listening, which includes listening with more than our ears and being changed by the experience of listening (Atkinson, 2002; Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia, 2021). It is with the intention of cultivating my capacity for deep listening that I draw attention to the experiences given voice by co-inquirers in my research and seek to deepen my own understandings through listening deeply and carefully to what they told me.

As this extract from my research journal written after viewing footage of the Seeing Her Stories: An Art-Based Inquiry (van Laar, 2020b) dinner party notes, “By sharing our stories through art, we weave our stories together, creating ways of knowing that connect us through a web of meaning. The web of meaning is like our shared story world. When we weave our stories together into a web of meaning our shared stories become a world that we can co-create and live within. We can affirm and validate our ways of knowing, our values, and life experiences. This is connecting, empowering, and life enhancing.”

Introduction

Interest, enablement, joy, and meaning are the life-enhancing qualities that were revealed through my investigation of the research question, “What can happen when a woman’s stories are seen?” I have started at the end here and will spend the remainder of the article describing how I came to learn that interest, enablement, joy, and meaning are life-enhancing qualities of sharing our stories through art, and why this is important (van Laar, 2019b, 2020b).

First, I provide a brief overview of Seeing Her Stories: An Art-Based Inquiry (hereafter, Seeing Her Stories; van Laar, 2020b), my doctoral research into sharing women’s stories through art. I unpack the layers contained in the subtitle of this article, “Listening for What’s Life Enhancing About Sharing our Stories Through Art”, and some of the meanings these words communicate. Next, I summarise the findings of my investigation into what can happen when a woman’s stories are seen. Then, I focus on the life-enhancing qualities of interest, enablement, joy, and meaning as they were described by participants in my research. Finally, I reflect on why deep listening is important in research and in practice, and I discuss this in the context of the changing political landscape of mental health in the Australian service system.

Seeing Her Stories—An Overview

Working as a creative arts therapist in the community, justice, health, and education sectors over the past three decades has grounded my interest in paying attention to women’s stories. I share the conviction of narrative therapists White and Epston (1990) that cultural and institutional stories perform values. These embedded values serve the interests of particular individuals and groups, often at the expense of others, and are integral to perpetuating and maintaining systems of power and the status quo.

My work with girls and women has exposed me over and over again to women who have been silenced in fear after being abused and disempowered. In my work I strive to enable people to feel safe enough to find art-based ways of telling stories that subvert oppressive power structures by being authentic to lived experiencing. While I identify as a woman and as female, I do not identify with socially constructed gender roles that are limiting or disempowering. I understand that within the spectrum of people who identify as women in many different ways, there are people whose stories are more marginalised than mine. However, my own stories of being a woman and an artist are part of a bigger social story in which particular stories are subjugated, less visible, less privileged, and afforded fewer opportunities to be seen (Richardson, 2016). At the beginning of this research, I had become interested in what would happen if I started to paint and make artworks that were neither conceptual, following the trend in fine arts education, nor explored a particular theme, as I had done (and as many artefacts of art therapy do) in the artworks presented in the book that emerged from my Master’s research, Bereaved Mother’s Heart (van Laar, 2008a), but which were simply artworks painted based on my interests, life, and experiencing at the time.

Listening for What’s Life Enhancing About Sharing Our Stories Through Art

The words in the subtitle of this article have been carefully chosen, and before we discuss them any further, I would like to expand on them a little. I start with “life enhancement”, move along to “stories”, “art”, then “sharing”, followed by “our”, and finish up with “listening”.

Life Enhancement

Life: the mysterious and animated ways in which we grow, metabolise, reproduce, and adapt, or the state of being human—our very existence, our own biography, or principles that are vivifying and quickening, that keep us alive (Macquarie, n.d.-b). To enhance life might mean to intensify the quality of and magnify life, improve life, and make life more valuable (Macquarie, n.d.-a). The notion of “life enhancement” signifies that, through certain activities, processes, and experiences, what may be thought of as “quality of life” can be enriched. Quality of life is often written about using terms such as “health” and “wellbeing”. The World Health Organization highlights that “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organization, n.d., p. 1).

As therapists, people usually come to consult with us because they want to feel better, or to improve their quality of life. Understanding how people actually experience and describe “life enhancement” should be part of our core business, yet often we feel compelled to justify our practice through evidence or data found in secondary sources rather than first-hand accounts from the people we work with.

Stories

It is through stories that lived experience is made into narratives that communicate a sense of things occurring over time. Stories are able to convey things that continue, as time does, like seasonal cycles and patterns of existence, and also things that change, like the weather, social attitudes, and the challenges that are inevitably part of life.

Art

Encountering art is a sensory experience; the creative arts engage our various senses through visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, and other stimuli. Engaging with art is a way in which we can enter into the lived world of another. We witness the living testimony, or traces, of their movements, expressions, communications, evocations, and energies that are evidence of creativity, of self-awareness, of sentience, of life. Stories are a form of art and can be conveyed in multiple art forms, not confined to words. Visual artworks, performances, and other forms are some of the shapes that stories take.

Sharing

Stories and art are made to be shared. They are relational configurations that communicate between people. Recorded stories can be shared across time and space, connecting people who share different geographical and historical locations. This sharing of stories can enable the sharing of lived experiences and the co-creation of meaning.

Our

In my research, the “our” refers to women. When I use the term “our” it indicates that I am a member of the particular social group of people whose shared stories I am investigating. In my case, I am a woman, and I collaborated with other women who were the research participants, or co-inquirers. We were all adults and middle class with some diversity in our ages, cultural backgrounds, dis/abilities, and sexual orientations. The research participants were women who volunteered after attending an exhibition of my artworks that was intentionally designed to share a woman’s (my own) stories through art. We were united by our interest in the research question “What can happen when a woman’s stories are seen?”

Listening

Listening carefully is a skill that therapists can intentionally cultivate in our work with people. However, in both therapy and research, the lenses of theory and the practices of interpreting and categorising can interfere with our capacities to remain present with what presents itself to us. Our challenge becomes to listen for things we do not already know, rather than to listen for things that confirm what we think we know. It is this kind of intentional deep listening that I sought to practise, learn from, and illustrate throughout the research that I am sharing with you here.

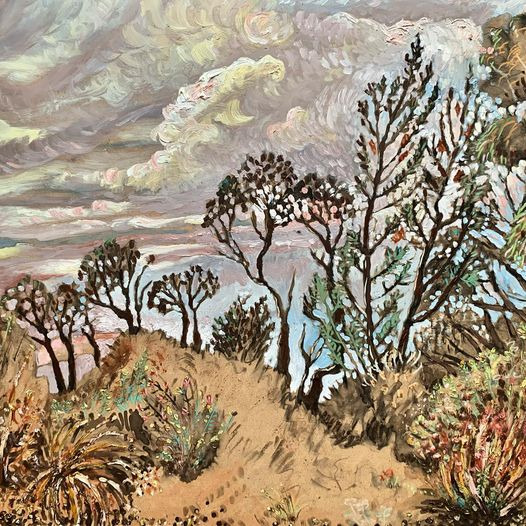

As a visual artist, I use my eyes and my whole body to listen. My painting practice helps me pay deep attention and listen to my subjects, be they people, places, or other expressions of life. For example, during the act of painting Backyard at Home (Figure 2), I had organised a dedicated time and space at a table looking out of my back window into the trees and shrubs and earth and sky outside. I had prepared this special time and place to focus. As I settled in to pay attention, my focus was drawn entirely into the here and now. I was completely absorbed in the present moment, my mind ceased wandering, and I felt an openness to receiving the information coming to me through my senses. Although painting is a visual art form, seeing can be a whole-body experience (Betensky, 2001). I became aware of nuances and details in the environment surrounding me, the subtle movements of foliage, and changes in the sky. Bearing witness in this way feels like a sacred act, an honour to simply be with, to participate in the moment by being fully connected in it, fully here, fully present, nowhere else. These are some of the qualities that I work to practise when I am listening carefully to people too.

So, when I say, “listening for what’s life enhancing about sharing our stories through art”, these words contain the layers of meaning that I have unpacked above.

What Can Happen When a Woman’s Stories are Seen?

This question is crucially important to the field of creative arts therapy, therapy in general, and, more broadly, the practice of creativity for health and wellbeing. Visual images may be thought of as ways to show stories in presentational forms that can be seen by others. Normative cultural stories steeped in patriarchal values dominate visual imagery in the popular media and many of the systems and institutions creative arts therapists find ourselves working within. The dominant stories of colonised Western culture are those told from perspectives that are male, Anglo, middleclass, scientific, heterosexual, and able-bodied.

As a heterosexual, cisgender, able-bodied, and middle class person of Nordic and European descent, I am a member of some of these socially constructed categories. My personal stories differ from these dominant stories primarily because they are stories from the perspective of a woman and an artist. As an artist, I seek to make authentic images of my lived experiences as a woman painter, rather than contribute to the dominant culture of visual stories about how to be a woman and how women should be seen. These are my unique stories.

Unique stories of lived experience include those from the perspectives of cultural and ancestral diversity; diversity in body, gender identity, sexual orientation, and kinship; living with disabilities and illnesses; neurodiversity; and others. The under-representation of diverse stories in society’s mainstream media, systems, and institutions can contribute to experiences of isolation; not belonging; being misunderstood, unacknowledged, unacceptable, or simply somehow wrong; or even the existential dilemma of not being real. Authentic and subversive personal stories are the kinds of stories that are given visual voices and spaces to be seen, witnessed, and validated in creative arts therapy.

I have been a creative arts therapist since 2000. During the past two decades I have worked within the changing landscape of Australia’s mental health system. This context is in a current state of review and adaptation. However, it is still a space that is dominated by the scientific Western medical model (State of Victoria, 2021), and a landscape in which, as a therapist working through creative and experiential practices, I have, many times, felt alien.

As practitioners interested in art and lived experiencing, creative arts therapists are curious about, and make space for, unique and subjugated stories to be created and seen. It is with this intention that I chose to investigate the under-represented stories that I have the greatest access to through my own lived experiencing—my own stories of being a woman and an artist. I also recruited a group of women who were interested in the research to broaden the stories and include the experiences of others with the intention of deepening my understandings about sharing authentic stories and how art works between people.

In my research, I used my own “her stories” and those of the women participants to explore the research question “What can happen when a woman’s stories are seen?” I did not, with a backward glance, ask, “What did happen?”, because I had not yet performed the actions that would generate experiences for me to examine. I was yet to create and exhibit my artworks and explore the lived experience of seeing these with a group of women participants. This is in keeping with both action-oriented and art-based approaches to creative arts therapy practice and inquiry.

In finding answers to my question “What can happen when a woman’s stories are seen?” I used our stories, visual and narrative, as my primary data—or source material. This was a collection of visual and narrative stories generated by me and the research participants over the course of the inquiry. In keeping with a practice-led approach to research, I have held the intention throughout the research for my findings to have their roots in lived experiencing.

In asking “What can happen?”, I sought to reflect on and learn from things that unfolded in the inquiry, with the intention of generating deeper understandings that can inform how we work using the arts with people, in situations and contexts that are infinitely inimitable and unrepeatable. I did this in honour of the great diversity of unique, alternative, subjugated, and unseen stories that live within all of us in various ways.

Methodology and Findings of the Seeing Her Stories Research—An Overview

Asking “What can happen when a woman’s stories are seen?” and investigating this question together with a group of women using arts-based approaches generated unpredicted findings. My arts-based research methodology included many creative and participatory methods that are described in detail in Chapter 4 of my book, Seeing Her Stories: An Art-Based Inquiry (van Laar, 2020b). Interested readers will find the entire e-book freely available on my website.

A core activity of the research was a focus group. The stories that I focus on to illustrate my topic for this article, “life enhancement”, were generated in conversations that took place during this focus group that I initiated as part of my research. During the focus group, the women who were the co-inquirers visited my studio for a dinner party. The art works that they were responding to were in the space, hung on the walls, exerting their physical presence. I called this event the "Seeing Her Stories dinner party". I have since learned the Boon Wurrung expression, “tarnuk—ut baany”, meaning “water in the billy”, which is used as an invitation to share food with each other and sit around and share stories (Stewart-Muir, 2022).

By working rigorously with all the material, broad thematic findings were generated. I found that when we share our stories through art:

-

“We can have a heightened awareness of our embodied experience in the present moment, through which we cultivate presence to ourselves, others, and the material world” (van Laar, 2020b, p. 132).

-

“Context makes a difference in our seeing, and this can impact on our experiences of taking risks and feeling safe” (van Laar, 2020b, p. 172).

-

We notice changes and become aware of continuity (van Laar, 2020b).

-

Relationships are strengthened and deepened, and “through our relating and connecting, we co-create” (van Laar, 2020b, p. 260).

-

“We can feel that our lives have been enhanced” (van Laar, 2020b, p. 296).

This article focuses, in particular, on the ways in which sharing our stories through art is experienced as life enhancing. Before discussing my findings in more detail, I briefly examine how the idea of life enhancement has been explored by other authors in the field of creative arts therapy.

Life Enhancement in Creative Arts Therapy Research and Literature

Authors in the fields of creative arts therapy, and arts and health, have linked life enhancement, health, and wellbeing with access to and participation in art-based activities (Binnie et al., 2013; Daykin & Joss, 2016; McNiff, 2016; Slayton et al., 2010). Some take a broad philosophical view, some focus on outcomes, and others look more closely at experiences of life enhancement by attending to the qualities of people’s lived experiencing. McNiff (2016) has offered an expansive perspective—that when we engage in art-based practices we participate in the creative life energy of the universe, and this energetic flow is the basis of all healing.

Many published studies look specifically for evidence of a reduction in unwanted symptoms such as anxiety or isolation, and an increase in protective factors or preferred states such as relaxation or cooperative behaviour (e.g., Slayton et al., 2010). Daykin and Joss (2016) responded to the perceived need for an evidence base in art-based practice by offering a framework for evaluating arts projects for health and wellbeing. This framework (Daykin & Joss, 2016) focuses on how target groups’ needs are assessed; ways to identify appropriate outcome measures, such as participation, mental wellbeing, and observed behaviour; and also ways to evaluate art program processes and impacts using quantitative and qualitative methods. Rather than focusing exclusively on outcomes for participants, this framework encourages reflection on the qualities of processes in art-based programs.

Binnie et al. (2013) expanded on traditional approaches to generating evidence of the links between art and wellbeing. The authors were particularly interested in links between seeing artworks and wellbeing, and asked, “Does viewing art in the museum reduce anxiety and improve wellbeing?” (Binnie et al., 2013, p. 191). While this question reflects the dominant practice of looking for evidence of reduced symptoms and increased health, in their discussion, Binnie et al. (2013) highlighted that:

Improvements of positive affect, which boost mental wellbeing in general, can also improve cognitive processes such as problem solving and social interaction (Ashby et al., 1999). This could suggest that positive reactions to the experience of viewing art in a museum could also be longer lasting than instances of a change in mood. (p. 192)

In this passage, Binnie et al. (2013) alluded to the idea that seeing artworks can have ripple effects that are ongoing and life enhancing—that somehow enrich quality of life for the viewers.

The World Health Organization (Fancourt & Finn, 2019) conducted a scoping review of the evidence linking the arts and health. Their findings confirmed the effectiveness of engagement in the arts to support health and wellbeing across the lifespan. Further, they recommended that global policymakers should “actively promote public awareness of the potential benefits of arts engagement for health” and “support the inclusion of the arts and humanities within the training of healthcare professionals” (p. 2). This report is still having significant effects, influencing more research to generate more evidence, deeper understandings of how the arts work, and public health policies that acknowledge and employ the power of the arts to support wellness and enhance life (Australia Council for the Arts, 2022).

Strong support for the recent establishment of the College of Creative and Experiential Therapies (C.CET) within the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA) is perhaps an example of one of the outcomes of a changing collective awareness about the links between the arts and wellbeing. C.CET’s emphasis on using more than verbal methods in therapy is an acknowledgement of the many forms that communicating, connecting, and sharing stories can take (Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia, 2022).

The growing interest in the arts, creativity, and mental health has given rise to public discussion, policy development, and debate about what constitutes evidence and how to produce it. For example, the Australian Council for the Arts (2022) report, Connected Lives: Creative Solutions to the Mental Health Crisis, found that:

Some argued that we need to develop measures that are consistent across both arts and health sectors and across the states and territories, developing a national database that tracks the impacts of arts programs in health settings. Others argued that cultural approaches to mental wellbeing require the development of cultural measures, and that working backwards from the expectations of the health system and its methods of data collection will not give us the data we need. (p. 21)

Unlike “impacts”, qualities that enhance life are, at the least, difficult to quantify, and are perhaps even unquantifiable. These kinds of life-enhancing qualities are experienced rather than observed and can be best understood through first-hand description rather than measurement.

Back in the early 2000s, artist, social activist, and art therapist Catherine Hyland Moon implored creative arts therapists to make use of artistic and poetic language for conveying art-based experiences. She said,

Poetic language draws the listener in, inviting empathic participation in that which is being described, and inviting authentic response. These qualities of poetic language offer potential antidotes for the problematic characteristics of the dominant discourse in medical and mental health, and a balancing effect for the medical model’s detached, diagnostic language for interpreting human behaviour. (Moon, 2002, p. 270)

I see this distinction as crucial for the field of creative arts therapy specifically, and relevant more broadly to the changing field of mental health and wellbeing services in Australia. Accordingly, in this article, I explore the qualities of “seeing her stories” that participants said contributed to the emergence of “life enhancement” as a consistent theme throughout the Seeing Her Stories research.

The Seeing Her Stories Focus Group Dinner Party

Early in the research process, I had been inspired by Ellis’s (2004) suggestion that the findings in autoethnographic research could be presented as a conversation between participants. I decided to host a dinner party and invite the women who had become participants through their interest in the research project. My intention was to generate such a conversation. I had already interviewed all the women individually about how they experienced seeing my artworks, and some of them had created visual artworks, musical responses, and written pieces in response, although they had not met as a group before the dinner party event. During the dinner party, the conversation itself became a forum for not only exchanging experiences and ideas but also generating new ones together. Nine women were present, including myself.

I sought permission from participants, which was granted, to have the dinner party focus group video recorded so I would have an accurate record of the dialogue. I hung artworks that I had created on the walls in my studio. These were artworks that the participants had responded to, and also portraits I had painted of some of the women present. I cooked a feast of vegetarian food. When everyone was present, and seated with plenty to eat, we began a conversation with the intention of sharing experiences in response to the question “What can happen when a woman’s stories are seen?”

The conversation lasted for approximately two hours, the participants were engaged and interested in sharing and responding to each other’s comments, and we finished the evening with one participant, Nicola, singing the song she had written in response to my painting The Woman on the Cliff (Figure 3; van Laar, 2008d).

I transcribed the video word for word, and then used the transcription and the notes I had taken when I reviewed the video images regarding gestures, interactions, and body language to create a story about what I saw in the focus group dinner party conversation. This writing became part of the source documents for my research. Significant excerpts from the dinner party were included in my thesis to help illustrate the findings that were generated through the inquiry.

Life Enhancement Findings in the Seeing Her Stories Project

The stories that were generated and collected through my research reveal the ways that the participants and I described the life-enhancing ripple effects of sharing our stories through art. We used words that relate to qualities of feeling interested, such as “discovery”, “inspiration”, and “fascination”. We communicated about being enabled through “possibilities for change”, “choices”, and “actions”. We shared our experiences of joy and meaning as we described our “great fun”, “wonder”, “realisation”, “understanding”, “beliefs”, “knowledge”, “values”, and “love”.

What follows is an excerpt from my journal of my conversation with one of the participants, Nicola, where she describes the links between her seeing of my story and her song writing, beliefs, and actions in the world. Nicola’s response to one of my paintings, The Woman on the Cliff (Figure 3; van Laar, 2008d), had prompted me to loan it to her for several months so she could hang it in the room where she composed music on her piano (Figure 4).

I ask Nicola if she can talk about any meanings, actions, or other ripple effects that she connects with her response to the painting The Woman on the Cliff (van Laar, 2008d):

Yes! And that’s the song! Be. For me, song writing is a subconscious thing; you don’t know what you’re thinking until you write it, then you look back on it and go, “Oh, that’s what I think!” Writing it cements it, and then it becomes an action. The response is subconscious, when you discover what it is and take your brain and you cement it, I realise what I’m thinking about, I write it down, I realise what I’m trying to say. It becomes a belief system and actions.

Nicola’s description here reflects the process of art as a way of knowing, or practice as research. Her description relates well to Heron and Reason’s (2008) expanded paradigm of knowing, and if we simplified her multilayered experiencing in accordance with their model, we could imagine that she has engaged in experiential knowing through her seeing of my image and later her own song writing, presentational knowing in the performance through music and words, propositional knowing in creating a belief system, and practical knowing about how to put her beliefs into action. The life-enhancing properties that Nicola depicted within this process include creating, discovering, realising, believing, and actioning. Her insights and learning are personally significant because they have application in her immediate life.

At the research dinner party, another participant, Marty, also highlighted discovery as an important and life-enhancing aspect of being involved in the Seeing Her Stories research project. For her, seeing the artworks and reflecting on the experience was connected with being exposed to many enjoyable feelings, an expanded sense of knowing, and new possibilities for practice. These were all part of discovering through Seeing Her Stories and its ripple effects, as she explained:

Well, I have been involved in research for a long time … And I think that research is about finding out about things that we don’t already know. And so for me, Carla’s Master’s research really showed me what arts-based research can be, and I found that amazingly inspiring because it is a little bit outside of the convention. We may know that these things exist, but to actually be closely exposed to it, enables you to know it, in a much more real way. And so I found that really quite fascinating, as well as very inspiring. …

I do think, that with this current project, it’s really been a privilege for me to see it unfolding, and along the way, it’s been wonderful to see the artworks, and to see the portraits, it’s all great fun, and I feel that the whole project is very enriching, but at the same time, that the sense of discovery, the sense of finding out about this style of research and what it can accomplish, and what it can communicate, and how this kind of research enriches knowledge, and contributes to understanding in a very complex way. It’s really wonderful to find out about this through Carla’s work, to be exposed to it, and to find out things that I wouldn’t be exposed to otherwise and have the opportunity to find out.

Marty highlighted a number of overlapping themes that help us to understand how being engaged in seeing artworks can be life enhancing. She acknowledges the complexity of knowing and understanding. The emphasis she places on meaning-making processes reveals to us something of her value system—that these things are important to her. She accentuates exposure to new research and involvement in the process as significant, and describes how these experiences are generative and inspiring, showing that her involvement has been motivating and energising.

During my dialogue with another participant, Jan, we spent time conversationally unpacking her experience of seeing my painting about driving along a road (Figure 5) and then responding through making a visual image.

Jan’s descriptions, like Nicola’s and Marty’s, illuminate how personal insights, meaning making, and possibilities for life-enhancing changes can all be part of the seeing experience and its flow-on effects. Jan noted that she is usually a “glass half empty” kind of person and was surprised that her response was to see the positive and joyful rather than the disturbing. She said, “Often when I am moved by a painting, it is something disturbing, and I respond to that, but in this I did the flip side, and I quite like that”. Jan’s contemplations demonstrated how she appreciated the life-enhancing shift of recognising and changing personal patterns towards more optimistic seeing.

Nicola similarly shared a personally transforming response to her seeing of The Woman on the Cliff (van Laar, 2008d) painting. Here, she talks about the seeing being a precursor to a pivotal moment in which she felt compelled to make a choice that enabled her to “move forward” in her life:

For me, it was about transformation. You either move through the darkness, and you get to the light, or you stay frozen where you are, and life ceases to exist. And for me, that then became that pivotal moment of—do you actually open those boxes, those dark, scary, dangerous places, you know, they’re all based around the same themes, pretty much, and get the gold, or do you stay like a statue forever, and not move forward?

So, for me, that kind of symbolised that moment in life, where you choose to face the demons, or lose your spirit, essentially.

The explorative discussion among the dinner party guests about their personal experiences of life-enhancing connections generated further optimistic understandings about the possibilities of engaging the arts for social wellbeing and healing. Nicola described how her perspective and valuing of art’s capacity to effect social change had shifted through the process of being engaged in the research project:

I think I came to this out of pure friendship and love for Carla. We worked together doing art with young people; we were always rambling about art and the value of art, and I’ve always had an internal conflict, about being an artist versus having economics and politics degrees and feeling that I wanted to do something constructive in the world, and so we’ve had many a discussion about the value of art, and ways that we can effect change. So this was a very fascinating process to be involved in. …

Thank you for the journey, for the things that it shone the light on. I think we all have this knowledge deep inside us, and then it’s moments like this that shines the light on it, and then you know that knowledge, and it brings it to the light.

In another brief exchange of dialogue from the dinner party between Jan and me, Jan had just finished telling the group some of the things she had appreciated about my process in this research, which included playfulness, discovery, decisions along the way, and experimenting. I was genuinely surprised: “That’s amazing”, I responded, reflectively, “Because everything that you just said, I felt that you were enabling me, to do that! Everything that you just said that you were enjoying!”

Jan replied, “I just thought you were going to go ahead and do it anyway, so I may as well go along for the ride and enjoy it!” This snippet illustrates how, in our meeting within this shared territory of unfolding and exploration, Jan’s ability to enjoy the process was enabling, empowering, and life enhancing for me as an art-based researcher.

As I read back over the words, ideas, and meanings that were shared and generated during the dinner party, I am myself moved emotionally by the experience of attending with presence to what was communicated, and how the knowings were expressed. My intentions throughout the project always included my wish to observe carefully, to encounter what is there, and to do this in ways that are art-based, interconnected, and organic. I held the intention to avoid psychologising or psychoanalysing the people and material in my study. The process kept me engaged, fascinated, and immersed for a decade of my life. I came to a realisation myself that I deeply desired to see what could happen if I stayed true to my conviction and belief in art. Could understandings, knowledge, and language emerge without privileging another field of practice? Could the central presence of art-based practice be a core strength and valuable in its own right? I have found that it can. The practices, language, and knowing of the arts provide me with a life-enhancing territory to explore, map, traverse, and meet with others in. This territory is enabling.

The image of the roller coaster ride (Figure 6) that hung behind me during the exchange with Jan visually speaks of the many ups and downs, twists and turns, glee and terror that were part of the shared journeys within this research story. It reminds me of the complex web of meaning that we have been weaving and creating together by sharing our stories through our arts and interactions concerning the Seeing Her Stories concept. The web of meaning we have created is life enhancing in multiple connected and interwoven layers. These layers include explorations through seeing and all of our senses, through inquiring, reflecting, unfolding, rambling, absorbing, responding, thinking, guessing, showing, exposing, bringing, sharing, song writing, speaking, and representing.

In our own words, the life-enhancing layers include our enjoyments—of ease, delight, liking, preferring, gratitude, fascination, pride, and amazement. They involve our insights, perspectives, realisations, recollections, awarenesses, understandings, discoveries, knowledges, and belief systems about the themes and patterns of our lives. They open up possibilities, opportunities, and actions that are generative, optimistic, enabling, positive, constructive, inspiring, and wonderful, through which we can face fears, remember how to be, work together, effect change, make valuable contributions, accomplish things, and involve each other.

As the participants expressed at the dinner party focus group, these layers enhance our wellbeing through fun, love, friendship, and togetherness; connecting us; affirming and validating our lives and existence. They are healing for us in ways that are enriching: they transform our life experiences, facilitate choices, and are co-creative and empowering. They support life-enhancing changes that occur over time as we choose, are moved, connect, open up, cease things, and emerge.

These complex layers comprise and co-create threads of meaning. They hold intentions, symbols, and values that, when interlaced together, weave story-worlds that become places and territories that bring quality to our lives when we inhabit them together.

The Importance of Interest, Enablement, Joy, and Meaning

I have illustrated that the life-enhancing qualities and ripple effects described by participants in the Seeing Her Stories project included experiences that were variations on the themes of interest, enablement, joy, and meaning. In attempting to understand how it is that these qualities are life enhancing, it is unpleasant but informative to imagine a life devoid of interest, enablement, joy, and meaning. In the absence of these life-enhancing qualities, life would become dull, detrimental, distressing, and futile. It is upsetting to imagine such a life; it would be a life of suffering and despair. This kind of existence can be conceived of as mental ill-health, dis-ease or “lost soul” (McNiff, 2016, p. 8). Many of us have had unfortunate opportunities to glimpse and partially experience these impacts during the pandemic restrictions. We have also witnessed how resourceful people can be in finding ways to access the important life-enhancing qualities of interest, enablement, joy, and meaning, and how people will turn to the arts and creativity as connecting and humanising experiences in times of extreme stress (Kiernan et al., 2021).

The understandings generated through the Seeing Her Stories inquiry are resonant with strengths-based approaches that emphasise resilience, empowerment, collaboration, motivation, hope, learning, and sustainability. As Hammond (2010) highlights:

The strengths approach as a philosophy of practice draws one away from an emphasis on procedures, techniques and knowledge as the keys to change. It reminds us that every person, family, group and community holds the key to their own transformation and meaningful change process. The real challenge is and always has been whether we are willing to fully embrace this way of approaching or working with people. If we do, then the change starts with us, not with those we serve. (p. 7)

Health and quality of life depend not only on the absence of disease but also on the presence of life-enhancing qualities such as interest, enablement, joy, and meaning. These are qualities that help us to adapt, respond, heal, regenerate, and grow, to feel alive, well, and soul-full. The qualities of interest, enablement, joy, and meaning can be ripple effects of participating in art-based projects, as they were for participants in the Seeing Her Stories research project, whose involvement began with the simple experience of viewing artworks painted by a woman. Understanding how these seeing experiences had ripple effects that flowed into participants’ broader lives in ways that were interesting, enabling, joyful, meaningful, and life enhancing adds a layer of meaning to previous understandings of the relationships between art and wellbeing, and is one of the distinctive contributions of this inquiry.

Life Enhancement—Implications in a Changing Landscape

The establishment of PACFA’s new College of Creative and Experiential Therapies reflects one of the many changes afoot in the landscape of understandings about creativity, mental health, and wellbeing in the current Australian context (van Laar, 2022b). In pandemic-affected 2022 and 2023, numerous, highly visible, major public projects have illustrated the interest in and uptake of creative approaches to improve quality of life. The Australian Broadcasting Commission’s nationally televised program Space 22 (Bassingthwaite, 2022) featured well-known participants engaging in art making to improve their mental wellbeing. Art Flow is a weekly program at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (2022) where participants are invited to take a break, contemplate art, reflect, and refresh their minds. “The Big Anxiety”, an arts festival that focuses on lived experience, psychosocial support, and reframing trauma and distress, has the mission to:

reposition mental health as a collective, cultural responsibility, rather than simply a medical issue. In this we respond to the report of Australia’s Productivity Commission (2020) which highlights the need for a more people-centred approach to mental health, and for a move beyond the narrow focus of our current mental health system on purely clinical services. (The Big Anxiety, 2022, “About” page)

The recent development of a new National Cultural Policy acknowledges and includes the mutual relationship between the arts, health, and wellbeing (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023). This affirms that the time is ripe to be part of conversations, influence policy, and help to co-create this changing landscape.

Recommendations of the 2021 Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System (State of Victoria, 2021) emphasised the value of lived experience expertise and sought first-hand accounts as evidence. These findings and recommendations demonstrate that powerful evidence can be generated by paying attention to what people actually tell us. We can be cautious about and actively resist the collection of meaningless and endless data, attempts to reduce people’s wellbeing to predetermined goals, outcomes, or KPIs (key performance indicators). We can question the usefulness of pathological hypothesising and, instead, ground our understandings of “what works” by listening carefully to people with lived experience. The final chapter of Seeing Her Stories (van Laar, 2020b) provides more breadth, depth, and detail about these implications.

Deep listening is embedded within the micro levels of our therapeutic practices. It can also play a lead role in the context of bigger social stories and how we move forward listening to one another co-creating a shared future.

Returning to the title of this article, Interest, Enablement, Joy and Meaning: Listening for How Sharing Our Stories Through Art Enhances Life, I hope to have conveyed some examples of how we can listen in ways that are creative, as well as layered with depth and intention. I hope to have demonstrated how caring about the expertise of lived experience can support us to discover things that we do not already know about what is life enhancing for people. I hope that something here connects with you and leaves you with an understanding that stories and art connect us in a continuing yet ever-changing web of meaning that we participate in and co-create, and that our participation and co-creation is necessary and important.